Top 10, 2011

1. Certified Copy

What separates the "real" from the pretender? And if you pretend for long enough, don't you become "real" in some way? The borders between the real and the simulacrum are in play in Abbas Kiarostami's deeply moving “Certified Copy”, my favorite film of the year. It's a man and a woman, he an art critic, she an antique shopkeeper, talking over the course of one sometimes harrowing Tuscan afternoon. Gradually something very curious happens: there is a shift, a morphing in their relationship until at certain point you feel like, "Right, what's going on here?" This is perhaps the most surreal film I know of that operates utterly in a realistic style. But that’s not what floors me about it, not why it was the most moving film of the year for me. It’s because it is two intelligent people speaking, without dogma, trying very hard to get to something real, to the heart of the matter. In the end nothing is settled, except that all you can be is who you "really" are. And that has to be enough, and is.

This was one of only two pictures this year I felt strongly enough about to go back to the theater and see again. And the other was…

2. The Tree of Life

A boy’s life in 50s Texas, while elsewhere in the universe, explosions are creating new galaxies. When held up against the birth of time and the farthest reaches of the universe, an individual life and death is at once put into perspective, and at the same time shown as something that, in its way, is just as exultant, epochal, and full of wonder. This is filmmaking that is as free as I’ve always hoped it could be, an unspooling ribbon of time.

3. Midnight in Paris

For everyone who's ever read “A Moveable Feast” and thought, right, Paris in the 20s: that was the time and place for me. Woody Allen had me right from the opening montage, which gave me the uncanny sense that my own memories and mind's-eye views of Paris were being projected onto the screen. There's been a bit of backlash against this one recently on the grounds that Allen doesn't do much more with the concept of an American whisked away into the world of the Lost Generation every night at midnight than drop names and sketch sketches. But the cameos are witty, and Allen has managed to do something truly remarkable: to get down on film something that is in the air in Paris, something to do with history and memory, romance and magic, and the tone for this fantasy is just right for capturing something so elusive: evervescent and light. An homage to a Paris that is as much a state of mind as anything, and a reminder that the Golden Age is in us.

4. Drive

Ryan Gosling as a stunt man by day, getaway driver by night. "Drive" is pulsating, electric, cheesy, sleek, ultraviolent. Movie magpie art: Winding Refn snatches up shiny bits that caught his eye from movies of the past and weaves his own thing out of it, dense with pop allusions. Riveting supporting work from Albert Brooks and Bryan Cranston.

5. Melancholia

A storehouse of the most unforgettable images of the year, and the truest movie I’ve ever seen about depression and its crippling downsward spiral, as embodied in the gorgeous body and wicked-smart performance of Kirsten Dunst, as well as by planet Melancholia on its collision course with Earth. No one who’s had any experience with depression will scoff at that all-ameliorating metaphor. I won't forget a nude Dunst serenely bathing in the moonlight of planet Melancholia, come to annihilate all.

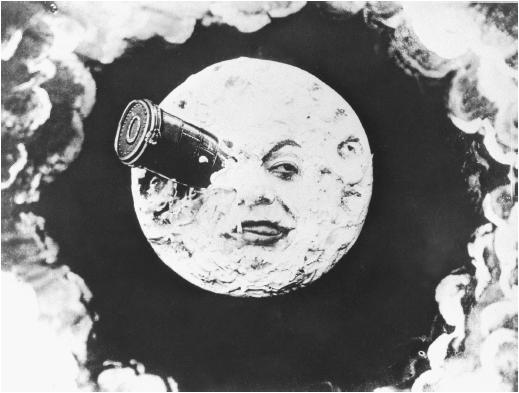

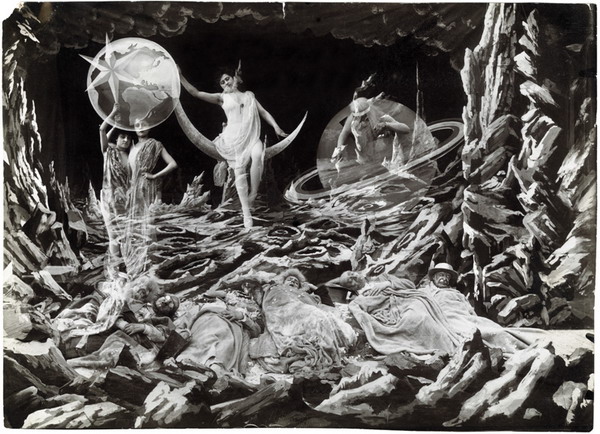

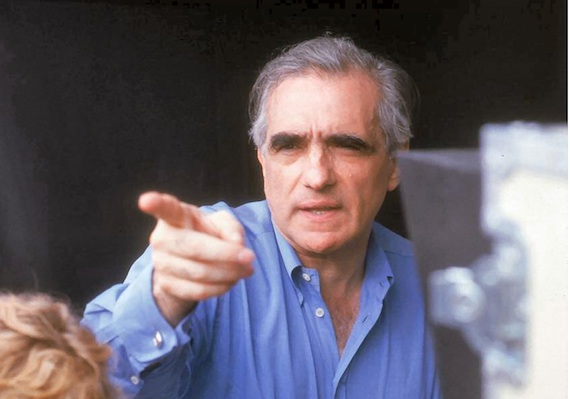

6. Hugo

This story about a boy who meets George Melies is a joyful homage to early moviemaking from Martin Scorsese, than whom cinema has no more devoted, loving preserver and keeper of the flame. When he includes footage from early film in "Hugo" (not just Melies, but the Lumiere brothers, Porter, Harold Lloyd), it's as if he's saying to us, the modern audience: we must treat early film with care, it is a precious treasure, and here, I want to show you why: because it is alive. His first children’s film, and one of his most personal.

7. Mysteries of Lisbon

The first four-and-a-half hour film I’ve ever seen at the theater. The passage of time becomes part of the experience. Though playful Brechtian touches are interwoven throughout, this is a more straightforward narrative than other films I've seen by Raul Ruiz, who died this year. An orphan, a noble-woman, a priest, a highwayman, one level of story atop another. You move through one layer until a character begins to tell a story and you drop down into the next level, burrowing deeper and deeper into the web of interlinking stories and identities, never getting lost. Of its many, may moments, there is never a dull one.

8. The Trip

Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon play sly versions of themselves in my favorite comedy of the year, Michael Winterbottom’s lastest amalgam of documentary and fiction. Banter and verbal volleys fly as our boys tour the restaurant inns of Northern England, from the one-upmanship as to who does the best Michael Caine to Coogan's sadly funny exegesis on the brilliance of Abba's "The Winner Takes It All". The film becomes surprisingly poignant.

9. Tabloid

Sex! Mormons! Bondage! Kidnapping! Another fascinating, funny documentary from Errol Morris, who as always is concerned with notions of "the truth," but amused more than ever here by its strangeness. In Joyce McKinney he found a character no fiction writer would dare invent. It makes me think of something I once overheard Christopher Hitchens say at a conference: "The truth never lies, but when it does lie it lies somewhere in between".

10. Uncle Boonme Who Can Recall His Past Lives

In rural Thailand a spirit returns in the shape of a big hairy Yeti to sit and visit with only mildly disconcerted relatives. A little snapper fish performs cunnilingus on a woman in a woodland pond below a waterfall. People watch as they become disembodied from their own bodies and step away from themselves. Apitchatpong Weerasethakul (or "Joe" as he was known when he studied in Chicago) gives us an acceptance of many levels of existence at once.

Honorable mentions:

Terri, Meek's Cutoff, Life, above all, Young Adult, Bridesmaids

-- December 22, 2011

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer