Phantom Thread

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Thursday, January 11, 2018 at 07:12PM

Thursday, January 11, 2018 at 07:12PM

It's all a story Alma tells, sitting by the fire. The latest film from the pen and lens of Paul Thomas Anderson, PHANTOM THREAD is a perverse, comic, enchanted period piece that plays with the medium while working within a host of traditions—chiefly, in Anderson's words, the Gothic romance with suspense, à la Hitchcock's Rebecca. It's a great film, for its zaniness, its mysteries, its strange elisions and shifts of tone I still don't pretend to quite understand.

Anderson's art does a lot of jumping off from various ideas, without quite sticking the landing, which can be breathtaking, but can also result in a curious (albeit fascinating) cryptic effect—the work can feel vague, sketchy. He's left a few rough edges here, too, but it's precisely that tension between rigorous preparation and bits that occur on the fly—the accidents, even—that give this picture its jazz, breath, and loose life. Right now, his range feels more limitless than any director of my generation.

Alma, played uncannily by Vicky Krieps, is a young refugee, we assume (the characterizations are still rather impressionistic), with a straightforward, poetic way of speaking. She confides the strange tale of her love for Reynolds Woodcock to a "boy doctor" (in Reynolds' derisive phrase). Woodcock (what a grand, suggestive name—the character is based, loosely, on couturier Cristóbal Balenciaga), is the co-founder, with his icy sister Cyril (a stellar Lesley Manville), of the House of Woodcock, elite dressmakers to royals and stars in mid-'50s London. This was perhaps the Golden Age for couture, and the offer is there, should we chose to take it up, to see it as a metaphor for the Golden Age of Hollywood. While the siblings are actually quite close—unusually so, in fact—they're a formal, stiff-upper-lip, postwar duo.

In late middle age, Reynolds is a confirmed bachelor, a meticulous, finicky workaholic. He's the latest in Anderson's gallery of obsessive masters, but whereas the There Will Be Blood model was demented or demonic, Reynolds registers as mainly prickly. (In his exacting standards, he's a form of critic, I suppose.) If his routine is thrown off, he gets grumpy. We get a sense of the settled morning routine that Alma will soon disrupt, watching the stately manse (another Gothic staple) come to life in the morning: Reynolds making sure every eyebrow is in place, the seamstresses climbing the steps to the workshops.

Driven to ply his craft at the highest level of quality, he can get carried away. (It's easy to see him as a self-satire of Day-Lewis or Anderson). After a frenzied bout of creativity he burns out, becomes melancholy, which is how he meets feisty Alma. She's a waitress near the country retreat where he repairs to renew himself. When he's on to the next thing—next woman, next project—he's a very hungry boy. He sure loves to tuck into a good old English breakfast, piling on the rarebit and sausages.

He initially conceives of Alma as just the latest in a long line of women who will one day be summarily dismissed, but she becomes his headstrong muse and lover. Only this time, the muse—the mannequin—talks back. Along with Cyril, the three comprise a classic Gothic love triangle, though Anderson doesn't overelaborate it, or, some would say, really develop it. Back in London, Day-Lewis does a hilarious slow burn as noisy Alma disrupts his breakfast with "too much movement." (The dark British sarcasm here is, in its way, as witheringly funny as the milkshake violence of Blood—it's fun with power dynamics).

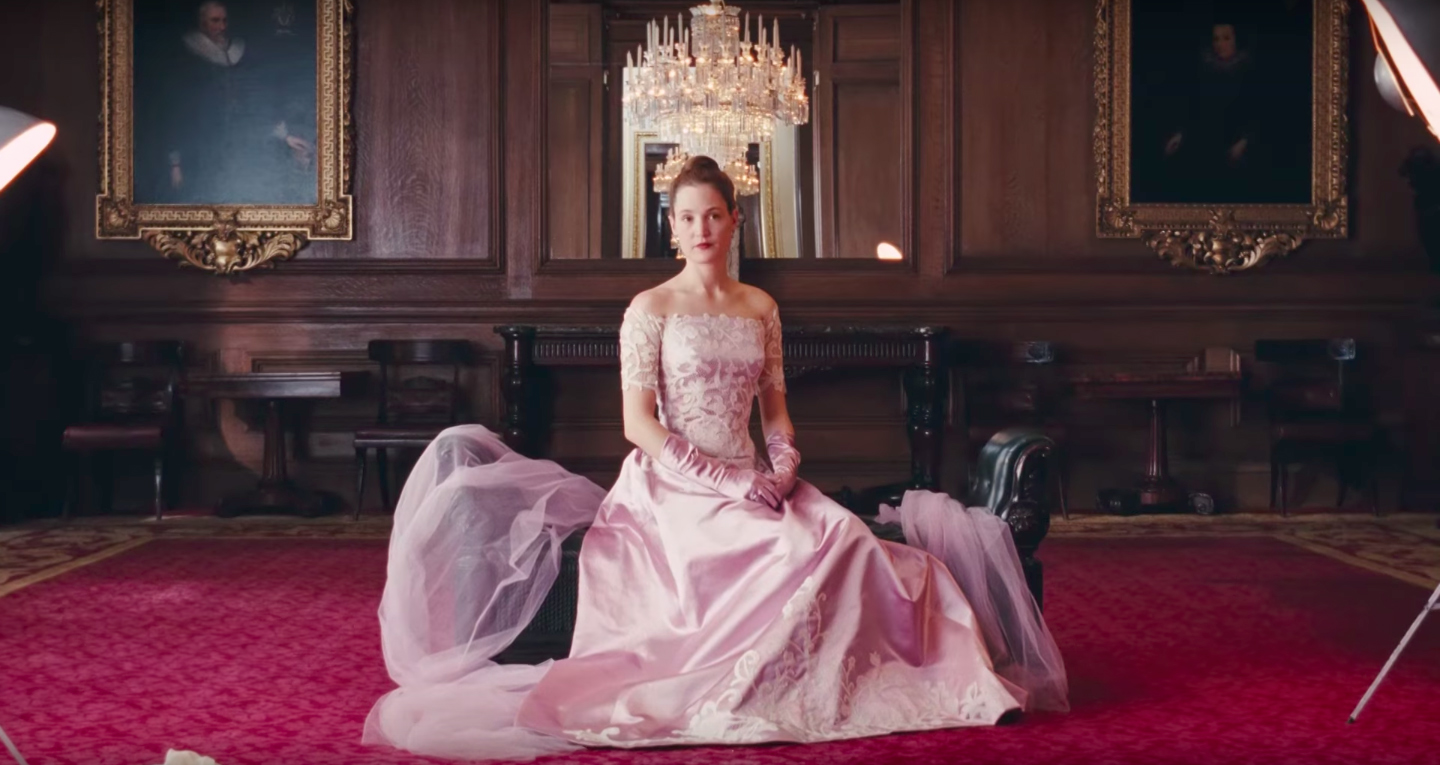

If this film is about how to sustain a life of both creativity and cohabitation, then certainly the model provided by The Shining's Jack Torrance is no way to do it. Yet, this noisy breakfast scene does seem a nod to the Jack-and-Wendy-at-the-typewriter dynamic. It's one of a myriad of Kubrick homages woven into the film—this is a P.T.A. joint, after all. When Alma and Reynolds bomb around the countryside in his automobile, Anderson straps the camera to the hood, using a fisheye lens like in A Clockwork Orange. Another nod to not-my-favorite Kubrick picture comes when a frenzied Reynolds, during a show at the House, becomes disheveled, stealing a secret look at Alma through a peephole, wild-eyeballed, as she displays one of his new gowns. (Costume designer Mark Bridges created the movie's gorgeous dresses.)

When another bout of paralyzing gloominess arrives, Reynolds becomes tender, open, splayed out in bed, and Alma has to drive, both literally and metaphorically. She takes a decisive, secret action to force him to slow down.

Reynolds feels he's cursed never to love. Transpose a couple of the words in that last sentence, and you have one of the secret messages Reynolds sews into the lining of his garments. (It interests me that there's more business about Reynolds' "curse" in the trailer than in the finished film.) Will love curdle to hatred? The bloom of the rose goes off their marriage quickly, and things seem headed for disaster when the old fuddy-duddy won't even go out dancing with Alma on New Year's Eve. This leads to a scene at the ball that receives a touching callback, and reveal, in the film's coda.

The distinctive cinematography is by Anderson himself, uncredited, working in collaboration with gaffer Michael Bauman and camera/steadicam operator Colin Anderson. They use lenses as precisely, and pointedly, as anyone since Kubrick himself in Barry Lyndon, a film recalled in a beautiful candlelit Christmas dinner scene. They've pursued a kind of funky beauty, intentionally going for a flat, fluorescent vision of the workshop. I do hope you live near a theater that's showing this picture in 70mm, such as we're lucky to have in Chicago with the Music Box. Seeing it on 70, you'll experience the textures the filmmakers have worked so hard to produce, meticulously experimenting with film stocks, lenses and lighting. I could see the blush on Alma's face; I could feel the lush purple fabric. At its best, this picture attains the wistful, sumptuous grandeur of a Luchino Visconti, or of Anderson's hero, Max Ophuls.

My mind also wants to associate the picture with Henry James and even Virginia Woolf—haunted, as Reynolds and the picture are, by his dead mother's ghost. "Always carry your mother with you," he tells Alma, letting her know he's secretly sewn a lock of her hair into the lining of his coat, above his heart. On his mantle he keeps a rather eerie, inscrutable photograph of his unsmiling young mother in her wedding dress; he tells Cyril that he can feel their mama reaching out to him—and that it's comforting to think the dead watch over the living.

For his grand finale in precision character-sculpture, Day-Lewis has found, in Reynolds, a role that allows him to range from stern patriarch to happy, helpless baby. He seems to have had a lot of fun doing it. (He's got a witty, literate Anderson script to work with.) It's all in his bowtie, I think. Day-Lewis always finds just the right touch to bring a character to life and, in a movie resplendent with telling details, Reynolds' bowtie tops it all off. As Reynolds, Day-Lewis doesn't just sit in a chair. He juts out a leg, greeting a countess festooned in one of his creations with a flourish, a bow, so that her entrance is an occasion. Slinging a Woodcock dress rescued from a slovenly dipsomaniac unfit to wear it (unforgettably characterized by Harriet Sansom Harris) over his shoulder, he twirls dramatically, elevating a sidewalk kiss into a grand romantic gesture. He's a serious man, gritting his jaw or glowering from beneath his eyebrows, but when he's in a flirty, playful mood he can be shy—his self-effacing smile is almost cute. Sometimes, when he's needy, a lock of his swept-back hair will dangle rakishly. Intense Method acting was the tradition that first fascinated me about screen acting, and Day-Lewis will go down in the history of screen electricity with his heroes Laughton, Brando, Clift and De Niro. He goes out on a note of great, kinky romance.

Relationships are strange things. How to rekindle love and creativity, down the years? Poised between instinct and deliberation, balancing on the fine line between destruction and creation, Anderson posits Alma's decisive action as a metaphor for the skill of figuring out how to live. Controlled risk—a bit of crazy, administered carefully. If you get it right, you'll find the hunger always comes back. In life, you might say, it's all just a matter of everything in the right dose.

(2017, 130 min, 70mm) Check the Music Box Theatre's website for showtimes.

Rating: ****1/2

Key to ratings:

***** (essential viewing)

**** (excellent)

*** (worth a look)

** (forgettable)

* (rubbish!!)

Reader Comments (1)

We just saw Phantom Thread Monday evening. Your excellent review captures it perfectly.