"So the screen reflects the ebb and flow of our imagination which feeds on a reality for which it plans to substitute."—Andre Bazin, from "The Virtues and Limitations of Montage," Cahiers du Cinema, 1953 and 1957

I've been thinking about Andre Bazin on this, his 100th birthday. I pulled the volumes by or about him down off of my shelf, and gathered up these voices as a birthday offering.

The roll call: Andre Bazin died in 1958, at the age of 40. (So, still quite a young man.) His sensibility was forged during the Occupation and Liberation. In fact, Dudley Andrew, in the preface to the 1990 edition of his biographical study, Andre Bazin, states: "Bazin's private struggles...vividly dramatize deep faults in that public terrain that goes by the names 'The Occupation' or 'The Fourth Republic.'"

He was the man who extricated Francois Truffaut from, in Truffaut's own words, detention home, military prison, and asylum.

Truffaut himself, writing in the foreword to the 1977 edition of Dudley Andrew's study, says: "I was an adolescent in trouble when I met him in 1947; I was fifteen year old, he thirty. And I will die without ever knowing why Bazin and his wife, Janine, became concerned enough about me to extricate me...I assert that Bazin's absolute good faith, his generosity, made him a character who stunned, intrigued, and excited us even to a point where we had to smile to one another to hide our emotions.

He co-founded Cahiers du Cinema in 1951, the "most influential film journal in history" (James Monaco), "intellectual home" to the likes of Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette. When the younger critics would get carried away, Bazin, in his essay "La Politique des Auteurs" (1957), went on to debate and critique the very auteurist movement he helped invent, or at least inspire. (This was in the spirit of a "family debate," says Bazin's biographer Dudley Andrew. It's as if Bazin, the "father," was debating his "children," like Truffaut.)

He was the "spiritual father of the [French] New Wave." (Michael Temple and Michael Witt)

He "laid the groundwork for the semiotic and ethical theories that were to follow." (James Monaco)

His two great subjects were Italian Neorealism and the new American cinema.

He felt a special affinity for Cocteau, Welles, and Chaplin.

Here's critic James Monaco, from How to Read a Film (2000 ed.) on Bazin's theories about the different ways theater and cinema work:

"The implications for cinema are that, since there is no irreducible reality of presence [of the actor and the spectator], 'there is nothing to prevent us from identifying ourselves in imagination with the moving world before us, which becomes the world.' Identification then becomes a key word in the vocabulary of cinematic esthetics. Moreover, the one irreducible reality is that of space. Therefore, film form is intimately involved with spatial relationships: mise-en-scene, in other words."

Monaco again, on Bazin's theories about the moving camera:

"...the moving camera has an inherent ethical dimension. It can be used in two essentially different ways (like focus shifts, pans, and tilts): either to follow the subject or to change it. The first alternative strongly emphasizes the centrality of the subject of the film; the second shifts interest from subject to camera, from object to filmmaker. As Andre Bazin has pointed out, these are ethical questions, since they determine the human relationships among artist, subject, and observer."

And Monaco on Bazin as existentialist:

"Always the existentialist, Andre Bazin was working to develop a theory of film that was deductive—based in practice. Much of this work proceeded through identification and critical examination of genres. 'Cinema's existence precedes its essence,' he wrote in fine existential form. Whatever conclusions Bazin drew were the direct results of the experience of the concrete fact of film."

Eric Rohmer: "Without any doubt, the whole body of Bazin's work is based on one central idea, an affirmation of the objectivity of the cinema in the same way as all geometry is centered on the properties of a straight line."

He remains relevant. Dudley Andrew again, from 1990: "No better example [of how Bazin's thinking can illuminate our own era] could be cited than the resuscitation in the 1980s of questions concerning the status of photography. Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes invite us to return to Bazin and to the distinctive view of 'the technologies of representation' that he held by virtue not just of his genius but of his openness to such contemporaries as Andre Malraux, Gilbert Cohen-Seat, Edgar Morin, and Jean-Paul Sartre, not to mention 'photographers' like Chris Marker." Presumably, we could trace his ideas, and his ethical concerns, all the way up to today's "virtual reality."

In his introduction to Bazin's posthumously published critical study of Jean Renoir (Jean Renoir, 1971), Francois Truffaut writes, "More than a critic, he was a 'writer of the cinema,' striving to describe films rather than to judge them."

Jean Renoir himself, in his foreword to Bazin's collected essays What Is Cinema? Volume 1 (1967 English edition):

"Our children and our grandchildren will have an invaluable source of help in sorting through the remains of the past. They will have Bazin alongside them. For that king of our time, the cinema, has likewise its poet. A modest fellow, sickly, slowly and prematurely dying, he it was who gave the patent of royalty to the cinema just as the poets of the past had crowned their kings. That king on whose brow he has placed a crown of glory is all the greater for having been stripped by him of the falsely glittering robes that hampered its progress. It is, thanks to him, a royal personage rendered healthy, cleansed of its parasites, fined down—a king of quality—that our grandchildren will delight to come upon. And in that same moment they will discover its poet. They will discover Andre Bazin, discover too, as I have discovered, that only too often, the singer has once more risen above the object of his song."

Happy birthday, Andre Bazin!

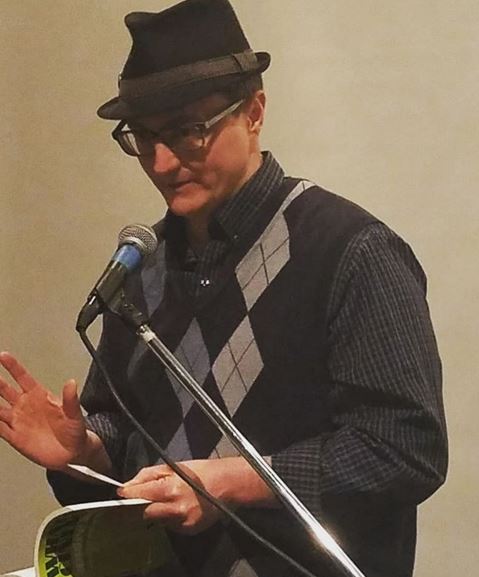

Postscript: Yours truly, reading at Andre Bazin's 100th birthday party at Comfort Station in Logan Square on April 18, 2018.

Wednesday, April 18, 2018 at 04:50PM

Wednesday, April 18, 2018 at 04:50PM

Reader Comments