Ten Movies I Liked, 2013

10 Films I liked, 2013

I can’t call this a survey of the 10 best films of the year, because I haven’t seen the totality of the year’s work. (Pesky day job!) Rather, here are 10 films I enjoyed. It was a year when the basic experience of the movies, the emotional and empathic experience, seemed to remain undiminished: their capacity to make us think, to make us feel. To freak us out, to get us hot. To make us laugh. To show us people faced with moral decisions and make us think about what we'd do if we were in their shoes. To put us in other people’s shoes in the first place.

1. Before Midnight “How long has it been since we walked around bullshitting?” Jesse asks Celine as they stroll along on a sun-kissed Greek island. It’s been about nine years, actually, since “Before Sunset.” That film unfolded in “real time,” but then, time is one of the subjects of these movies. It’s become a series, though it wasn’t planned that way, a collaboration between Julie Delpy, Ethan Hawke and Richard Linklater. 1995’s “Before Sunrise” was about an enchanted evening when time seemed to be suspended. That night left Jesse and Celine with an impossibly romantic image of the other. “Before Midnight” is about what happens when that romantic image becomes a real person. It’s also about middle-age. (I’m the same age as Jesse and Celine, so these pictures feel personal for me.) At one point Jesse and Celine sit and watch a sunset. “Still here,” Delpy says. “Still here.” And finally, “Gone.” Yes, the day will close, and yes, we’re only passing through. But by the end of this film, after that bravura extended scene in the hotel room where everything seems to teeter on the edge of flying apart--breathtaking, excruciating, hilarious, heartbreaking--Jesse and Celine make the choice that they will see the day out together. “Before Midnight” is more honest, more suffused with joy and sadness and truth, than anything else I saw this year.

2. 56 Up In 1964 a handful of British seven-year-olds from different backgrounds were asked, on camera, their views on life. Originally this program’s point was to see if the seismic shifts of the 1960s meant changes for Britain’s class system as well. We check back in with them every seven years, so that so that when we see the latest “Up” movies we’re also looking at ourselves, in a way. Those kids we saw dancing happily to the new beat music at the end of “7 Up” are now 56. The Up Series is about the moments that make up a life. It’s about love and the passage of time. At the end of this film, however, I came away feeling like there has been a secret theme to this series all along: happiness. It gladdened me to see that, for the most part, our “Uppers” have had a strong foundation when the winds of changes shift.

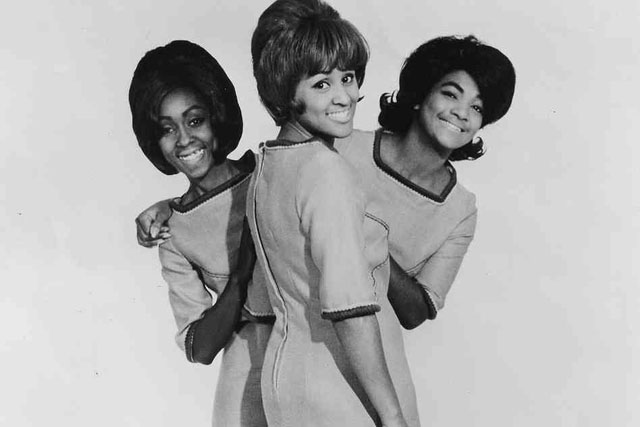

3. 20 Feet From Stardom A documentary about backup singers, this is also about dreams. It’s the story of the role of black women in rock & roll. There is much electrifying performance footage: Lynn Mabry with Talking Heads, Claudia Linnear behind Joe Cocker and George Harrison, Darlene Love doing a supercharged “Fine, Fine Boy” with a deliriously happy Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. We see Merry Clayton, who recorded that apocalyptic vocal on the Stones’ “Gimme Shelter” make her (ultimately unsuccessful) bid for the front of the stage, performing a powerful version of Neil Young’s “Southern Man.” The filmmakers linger on Lisa Fischer (who’s taken that “Gimme Shelter” solo onstage with the Stones since 1989). They enjoy basking in her otherworldly scat singing and her radiant smile just as much as we do.

4. Gravity This year’s purely cinematic experience, a story that could only be expressed fully in the medium of cinema: not as a novel, not on the small screen nor stage. Alfonso Cuaron’s elemental tale of survival put us in a spacesuit with America’s sweetheart, Sandra Bullock (in a fine performance), and cast us adrift in the cosmos. We felt everything she felt, as she first accepted that she would die, and then chose to fight to live. The thrilling images were vast, vertiginous; the sounds could be as intimate as a heartbeat.

5. 12 Years a Slave Here is another tale of survival. Solomon Northup (Chiwitel Ejiofor), a free, educated black man, a violinist, was kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841. He ended up deep in Georgia on the plantation run by a dissipated, sadistic man called Epps (Michael Fassbender), his fate to be some kind of crucible for Epps’ feverish shouldering of the “White Man’s Burden.” In order for a period movie to work, the very atmosphere has to be right, from costumes and set design all the way down to supporting performances and the language, here written by John Ridley, adapting Northup’s 1855 memoir. Here everything is right, so that raw white supremacy feels as natural and American as breathing. The director, Steve McQueen, and his cinematographer, Sean Bobbitt, create images rich in texture. Alfre Woodard has only one scene, but it’s chilling. Fanning herself on the porch, her smile never fades as she utters a chilling line: the curse of the pharaohs got nothin’ on what’s going to happen to these slavers. And after a time we’ve seen so much brutality that we’re calling out for “Django”: for an avenger, for a cathartic bloodbath. But this film shows the reality: the heroism was just to survive, and that left you feeling like no hero at all. Actually, the picture it most put me in mind of is Pasolini’s almost unbearable “Salo,” about a group of fascists holed up in a castle in the terminal days of WWII, acting out sado-masochistic fantasies on the young men and women of the village. Chiwetel Ejiofor’s expressive performance translates Northup’s inner life into visual terms. Our friend Dwight Henry has a small role. (Karolyn and I had the pleasure of meeting the great man at his Buttermilk Drop Bakery in New Orleans earlier this year).

6. Much Ado About Nothing Back when Joss Whedon’s TV shows “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and “Angel” were on the air, I used to read about how his troupe would come round to the house and drink wine and perform Shakespeare for their own amusement. His black & white staging of Shakespeare’s fin-du-siecle (1599) screwball comedy has much of that feel, and it’s all the better for it. The actors are playing in the dress-up box a bit here, while also inhabiting the characters fully. Whedon's happy lovers capture the spirit of Shakespeare’s fanfare, set to music by Whedon: “Then sigh not so, but let them go, and be you blithe and bonny, converting all your sounds of woe/into hey nonny, nonny."

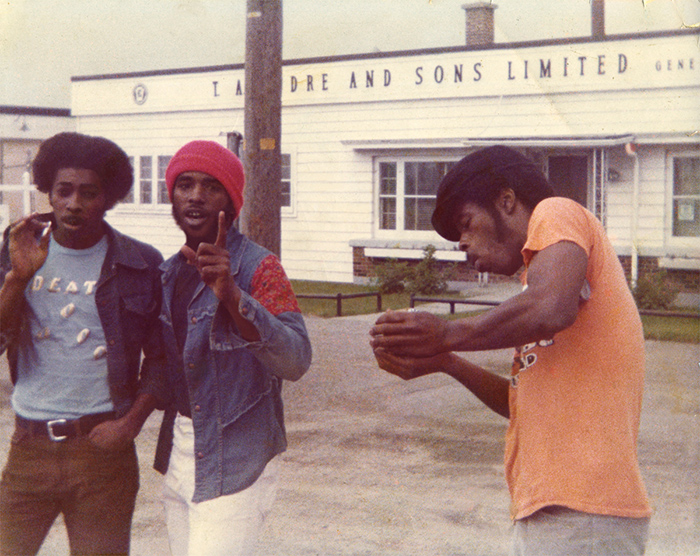

7. A Band Called Death You should see this film if you’re excited about rock ‘n’ roll, or even if you’re not: it’s a really good story about three African-American brothers in early-70s Detroit who formed a band that the band’s leader, the late David Hackney, insisted on calling Death (though we learn that the name was conceived as anything but a nihilistic concept—in fact it was a spiritual thing that came to him as he reflected over his father's death—of course everyone took it that way). The brothers played punk years before punk, and at a time when audiences had certain preconceived notions about rock 'n' roll as music white people played (not that that's changed too much). Death was forgotten until Drag City re-released their 1975 album a few years ago. The two surviving Hackney brothers remember their brother David as a visionary who insisted on being true to his vision, even though the audience wasn’t ready. Now, four decades on, they’re out there playing the music again to excited audiences.

8. Stories We Tell All families have stories. All families have secrets. Sarah Polley, a director I admire (“Away From Her,” “Take This Waltz”), made this film when she discovered that her father (the actor Michael Polley), who raised her after her mother died, is not her biological father. While it’s a film about looking for the truth, what you have to keep in mind is that this is a family of actors and professional storytellers. In a sense it’s their job to make us believe things that aren’t true. Polley remains an artist, not some dull, objective receptacle of “truth,” and she doesn’t pretend otherwise. Her instinct is to tell stories, to play, to play even with film texture. (She creates “home movie” footage so skillfully that it’s jarring when she eventually pulls back the camera to reveal herself orchestrating the entire scene.) This movie is also about how for each generation our parents remain essentially mysterious. It’s about imagery as a form of memory. And it's a portrait of Polley’s mother, a life-force who died too soon.

9. This Is The End Helming the director’s seat for the first time, Seth Rogen and co-writer Evan Goldberg got a bunch of real-life friends (James Franco, Jonah Hill, Michael Cera, Danny McBride, Craig Robinson, Emma Watson etc.) to play twisted versions of themselves. It’s about how horribly these people would behave if the Rapture were actually upon us. (None of them was shot up into heaven of course). They have a lot of fun making fun of their own personas. It’s a bit insular, presupposing that you know these people and their work. While the special effects are funny, the laughs mostly flow from human-scale foibles like pretensions and vanity. You can almost hear Rogen and Goldberg sitting around saying, “Wouldn’t it be funny if…?” And for the most part, it is.

10. The World’s End

Another movie where a bunch of mates sitting around saying “Wouldn’t it be funny if…” got their vision up onto the screen. It’s about the end of the world as well, and about my generation, sort of. It’s by the team who made “Shaun of the Dead”: Simon Pegg and Nick Frost, who co-write and star, and Edgar Wright, who directs. These guys are the same generation as me. The story is about a group of estranged old friends, settled into a middle-aged rut, who reunite to finish the pub crawl the never finished 20 years ago, when they were young and invincible. Pegg plays the selfish, charismatic rebel (the “cock”) who used to cheerfully get them all in trouble back in the day. The filmmakers establish characters and a story and an everyday world, so that by the time the jolts come, they really jolt. (You know this crew wouldn’t stick to a straight story). I like the idea that the Starbuck-ization of English country pubs is the advance warning of an alien invasion. Actually, the idea that human beings are being steadily replaced by robots would explain a lot. While this movie eventually becomes repetitive, it's mostly a pleasure. Features an early-90s Britpop soundtrack, the music of the characters’ youth. (And ours, some of us).

I should also mention Lee Daniels’ The Butler, Die Welt, Despicable Me 2 (for most Minions madness), The Harvest, Blue Jasmine

--December 13, 2013

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer