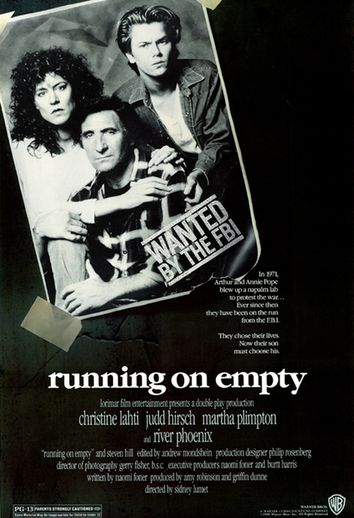

Running On Empty

Friday, March 16, 2012 at 04:36PM

Friday, March 16, 2012 at 04:36PM  I threw this one on as part of my ongoing program to catch up with Sidney Lumet pictures I’d missed. It rather blindsided me with how well-observed it is. It's that rarity: an honest film.

I threw this one on as part of my ongoing program to catch up with Sidney Lumet pictures I’d missed. It rather blindsided me with how well-observed it is. It's that rarity: an honest film.

I imagine the characters of the parents here--former 60s radicals who’ve been raising their family “underground” ever since their bombing of a napalm factory accidentally blinded and paralyzed a janitor--are modeled on Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayres of the Weather Underground. In Christine Lahti and Judd Hirsch the filmmakers have found the very embodiment of these roles. Lahti actually reminded me a bit of Dorhn, physically.

Every few years when they feel the heat getting too close, the family has to beat it to a new town and assume new identities. They've made plans for every eventuality, including where to meet if the kids, a teenager and a 10-year-old, need to flee when the parents aren't home. When we meet them in the late 80s, that's exactly what's going down.

The film not only resonates with some of my long-term fascinations (the left, the antiwar movement, the cultural upheavals of the 60s), it has a protagonist, the teenager played by River Phoenix, who shares my particular generational take on them. I was born the same year the bombing is meant to have taken place: 1971. That means that, like the Phoenix character, my understanding of it all can never be direct. I experienced "Running On Empty" as a film about how my generation was shaped, in ways of which we might not even be aware, by the weight of what went down before we were even born, in a era more volatile than we can perhaps imagine.

I’m struck by the intelligence of Lumet’s direction. He mostly permits us to suss out the dynamics and back-stories of this family just by letting us observe them. Hirsch is a red diaper baby; Lahti the child of wealth and privilege who rebelled against her upbringing. Late in the movie we witness a reunion with her long-estranged father. It is beautifully played, the actors expressing so many things at once: regret, anger, the living after all these years with the pain of a redemption that can't come, the eyes that plead for each to understand the other. In this small scene with this father and daughter we get a feel for how the war tore the society asunder at all levels.

While we get a feel for how crazy a life on the lam is for the kids, we also observe how to them it just seems normal. We see how much the father and mother love their boys. They are essentially humane people. Even in the desperate days of the anti-war movement, they were never able to dehumanize ordinary Americans in a way that would allow them to be harmed as "collateral damage", the way some militants did (such as their erstwhile comrade who turns up all these years later wanting them to rob banks: he sees it as a way to finance what's left of the "movement").

The tragedy is that it was precisely this love for humanity that led them to plant the bomb which ended up maiming an innocent man. Why’d mom and dad do it? the 10-year-old asks his big brother one day, and I love the way Phoenix answers him in just one sentence, and in a way that even a child can understand: the government was pouring napalm on people. If viewers of my generation can't imagine why planting a bomb ever seemed like anything other than an insane idea, in that irreducible line we are also made to understand the corollary. The government was pouring napalm on people. Wouldn't you do anything, everything you could to stop it? (In this way, too, the picture is in keeping with one of Lumet’s primary thematic concerns: people taking a stand against injustice.)

It feels like a real family, what Lumet and the actors have got down on film here. The birthday dinner scene in which they spontaneously begin to dance to James Taylor is one of the great joyful moments I’ve seen in movies recently.

There’s a nice bit that shows how an antiauthoritarian stance can complicate parenting: when Hirsch won’t let his son attend a classical performance, it's because classical is the music of the white, privileged male and “it’s not rock & roll”. Phoenix calls him on it, telling him he’s full of shit, and when the old man chafes the teenager says, hey, YOU were the one who taught me to be antiauthoritarian.

I also really like the relationship between River and Martha Plimpton, who plays his girlfriend. Like them, I was a teenager when this movie came out. In that fascinating way in which a film can’t help but record the time in which it was made and the world in which the actors were living, I felt like I was watching people who had the same experience I did of being an 80s teenager.

Rating: ****

Key to ratings:

***** (essential viewing)

**** (excellent)

*** (worth a look)

** (forgettable)

* (rubbish!!)

Reader Comments