Tabloid

Here's the latest from Errol Morris, one of the foremost documentarians of our time. He's given us, among others, "The Thin Blue Line," which freed a man wrongly convicted of murder and got the guilty man locked up; the deeply moving "Gates of Heaven," which only seemed to be about pet cemeteries (its real subject, in Roger Ebert’s words, was “the central mystery of life”) and "Fast, Cheap & Out of Control," which we took my young stepdaughter to see more than a decade ago. (It turned out to work quite well as a kid's movie.) A few years ago he gave us a portrait of Vietnam War architect Robert McNamara (the fascinating "Fog of War"). That's all well and good, but now he brings us a story that has the kind of stuff people are really interested in: sex and bad behavior.

I knew nothing about Joyce McKinney when I went into the picture. Her story is one of the most bizaare you're likely to hear, and it just keeps getting weirder. Joyce herself is one of the funniest, saddest characters I've encountered in movies in recent memory. When we first meet her, in footage from the early 80s, she looks like a princess. That's fitting: she seems to imagine herself as a princess in a fairy tale. She's even reading from a storybook, her own manuscript telling in her own words the tale that had so delighted Britain just a few years earlier: how the princess met her Prince Charming, only to have him spirited away from her by dark forces. The young Joyce exudes sweet innocence with her farm-girl accent; at the same time she glows with a kind of warm, sleepy, sated sexuality. Then we see talking-head interviews with the Joyce of today, a woman of 60 who still exhibits the same spirit and smile.

As a young beauty queen (a former Miss Wyoming World) McKinney landed in Salt Lake City and, for some inexplicable reason, fell in love virtually at first sight with an unassuming, heavyset Mormon missionary called Kirk Anderson. What did it for her, in her memorable phrase, was his "clean skin". (Anderson refused to participate with this film). When the church removed him to England, she hired a pilot and, along with some male hangers-on, tracked him down. (Joyce was always in the company of men who were obsessed with her to the same extent that she only had eyes for Kirk).

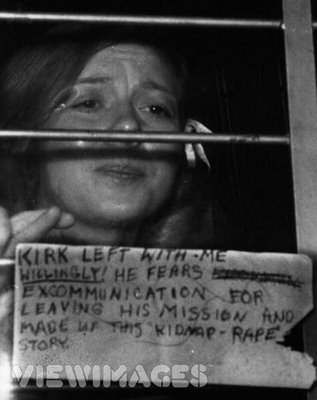

What happens next depends on to whose story you believe. According to Joyce, Kirk went away with her willingly. They repaired to a cottage in Devon. She admits that she tied him to the bed, having read that a little bondage is the way to dispel psychological impotence.

(Morris interviews an ex-member/whistleblower on the sexual repression of the Mormon church: he discusses, among other things, the "chastity suits" they make you wear. In fact one of McKinney's issues with this film is that it doesn't focus much more on the Mormons as a “cult”; she has plenty to say on the church’s evils, such as inculcating people with guilt and shame about the God-given pleasures of sex. It strikes me that as an avowed Christian she’s on rather shaky ground here.)

In her narrative they proceeded to have three wonderful days of sex and food and togetherness. The other story, the one trumpeted in the tabloids throughout Britain in 1977, is that she kidnapped him with the aid of chloroform, hired heavies and a very real-looking fake gun, "CHAINED" him to a bed "SPREAD EAGLED" and raped him for three days. (Morris blows these words and others up onto the screen into huge, tabloid headlines. Film theorist James Monaco has written that cinema "raises fundamental questions about the relationship of life and art, reality and language," and it strikes me that this movie offers a full course on that idea.)

The fact that the "victim" here was a man makes the accusations of kidnapping and rape not exactly funny, perhaps, but...unusual. The question arises of whether it's even possible for a woman to rape a man. Joyce thinks rather not (she has a brilliant line which I shall let you discover for yourself). I am inclined to agree with her, if I’m honest.

After a brief pre-trial tenure in Epsom prison, the star of “the Mormon sex in chains case," the “Case of the Manacled Mormon," proceeded to cut a swath through late-70s celebrity culture in Britain, briefly outshining even the hottest movie stars of the time. Keith Moon was photographed giving her a smacker. The tabloids began looking into her background; The Daily Mirror dug up photos documenting what seemed to be a past life as a S&M hooker (forgeries, she claims). There ensued a sort of competing-narratives war with Britain's other best-selling tabloid, The Daily Express, each telling different versions of her story.

(The movie is also about the ruthlessly aggressive tabloid culture in England. It had the good fortune to be released at the time of the shuttering of "News of the World" and the phone-hacking scandal exposing the cozy relationship between Rupert Murdoch's NewsCorp/News International and the top of Britain's government and police force. Not to mention in the wake of the Casey Anthony verdict, the ultimate tabloid case. This story is of course exponentially lighter in tone than all of that)

(The movie is also about the ruthlessly aggressive tabloid culture in England. It had the good fortune to be released at the time of the shuttering of "News of the World" and the phone-hacking scandal exposing the cozy relationship between Rupert Murdoch's NewsCorp/News International and the top of Britain's government and police force. Not to mention in the wake of the Casey Anthony verdict, the ultimate tabloid case. This story is of course exponentially lighter in tone than all of that)

As it happens, McKinney never finished writing her story herself, and now Errol Morris has done his version. He is a great storyteller. This movie is not investigative journalism: Morris is not interested in "getting to the bottom” of McKinney’s story. He's interested in the mystery of the narrative, in reflecting it in as many facets as possible. After all, as I once heard Christopher Hitchens put it, "The truth never lies, but when it does lie it lies somewhere in between."

The competing narratives are one of the fascinating things about the movie. Actually, it's now spilled off-screen. The subject of the story isn't being quiet. McKinney has her own idea about what kind of story this is, and she wants to tell it her way. She for one does not see the humor in it. This is not a sex comedy to her, it’s "tragic and intellectual". McKinney is in many ways the perfect Morris subject; his films are always about obsession on some level. (Filmmaking itself is obsessive.) The problem is that the man who trades in ironies has finally met a woman quite without any sense of irony whatsoever. She can claim, in all sincerity, to have never wanted anything more from life than a "little Leave-It-to-Beaver house with a white picket fence." (Among other thing, the film is a fount of great lines.)

To Morris’ bemusement, she's apparently been attending more festival screenings of the film than he himself has, decrying the film and trying to get her side of the story out. She says she intends to sue. [Check out the video of her appearance at a New York screening. I admire how at no point does Morris try to silence her. Note her maniacal laugh at the end.]

It would be wrong to understate the extent to which McKinney is herself an actress, so to speak. She loved assuming new identities with her main partner in crime (a fellow called Keith May, now deceased), dressing up with him as an Indian couple, or even a pair of nuns, eluding arrest and obtaining fake passports to get back into the U.S. She's a very shrewd manipulator, but never a malign one. You can see it in the photos from the time: that radiant smile. There's never a trace of shame. She's got Bettie Page's ability to exude such pleasure in being naked that even the S&M shots that turn up never really seem tawdry.

It would be wrong to understate the extent to which McKinney is herself an actress, so to speak. She loved assuming new identities with her main partner in crime (a fellow called Keith May, now deceased), dressing up with him as an Indian couple, or even a pair of nuns, eluding arrest and obtaining fake passports to get back into the U.S. She's a very shrewd manipulator, but never a malign one. You can see it in the photos from the time: that radiant smile. There's never a trace of shame. She's got Bettie Page's ability to exude such pleasure in being naked that even the S&M shots that turn up never really seem tawdry.

I like how Morris doesn't condescend to tabloids. You can tell that he actually gets a kick out of them. He invigorates the movie with that same pulpy, exploitive quality, both in its look and in the way it tells its story. "I am no different than any of the men in this story," he's said: obsessed with Joyce. There is a bit of a feeling of taking glee in a situation in which someone may have been hurt, but I suppose that’s part of what people enjoy about tabloids themselves. (You have to be completely non-moralistic to enjoy them; I suppose at some level there's still vestiges of a tut-tutting leftist in me who believes that the masses would be much better off if they were picking up, say, Chomsky pamphlets on the way out of Jewel instead of these rags.)

Re-reading Roger Ebert’s review of Morris’ “Gates of Heaven”, it struck me how relevant it was to my thinking about this film. "Heaven" is one of Ebert’s favorite movies, a film about pet cemeteries and the bond between animals and humans (often eccentric ones). He writes that “Heaven” became “a litmus test for audiences, who cannot decide if it is serious or satirical, funny or sad, sympathetic or mocking.” Much the same is true here. The audience I was with laughed long and hard, and so did I at times. However, some other words from Ebert’s review of “Heaven” speak to me:

“The signs on the pet markers are eloquent in their way. ‘I knew love; I knew this dog.’ ‘Dog is God spelled backwards.’ ‘For saving my life.’ At the end of the film, having laughed earlier, we find ourselves silent. These animal lovers are expressing the deepest of human needs, for love and companionship.”

When asked late in the film if she still loves Kirk to this day, McKinney replies, tears welling up in her eyes, that she still does and that she always will. That much I believe is true. The part I wasn't laughing at.

And hey, she loves dogs, too. I didn't even touch on the pit-bull cloning. That I will leave you to discover for yourself. (I told you the story just kept getting wierder.)

Rating: ****

-- July 17, 2011

Key to ratings:

***** (essential viewing)

**** (excellent)

*** (worth a look)

** (forgettable)

* (rubbish!!)

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer

Reader Comments