RAISING BERTIE

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Wednesday, June 14, 2017 at 08:27AM

Wednesday, June 14, 2017 at 08:27AM

Margaret Byrne's empathetic, thought-provoking RAISING BERTIE begins with a rushing road. A teenager, Reginald ("Junior"), comes bicycling towards us. The film introduces us to him and two other young African-American males living in Bertie County, North Carolina, and over the next hour and a half we get to know them. To make this film, Byrne ensconced herself in the community for six years, reminding me of the way Barbara Kopple settled into HARLAN COUNTY, U.S.A. We watch these boys grow into men, sharing in their hopes, dreams and struggles. Thus, RAISING BERTIE deserves a place beside the great achievements in longitudinal film, from Michael Apted's UP series to Richard Linklater's BOYHOOD to Steve James's HOOP DREAMS. It upholds the worthy tradition of social-issues filmmaking as practiced by Frederick Wiseman, Albert and David Maysles, Gordon Quinn, and Chicago's own Kartemquin Films, which produced. It's also fair to say that it makes us think anew about some of the problems inherent to cinéma vérité.

We hear a lot about at-risk urban youth, less of their rural counterparts. Rarer still is an approach that values what these young men feel—in a word, that treats these lives as if they matter. After all, our culture teaches young men to keep it all in. While the cliché is that these men are not "articulate," in fact there is a music to their language. The film often subtitles their speech, for the benefit of we outsiders who don't have an ear for it.

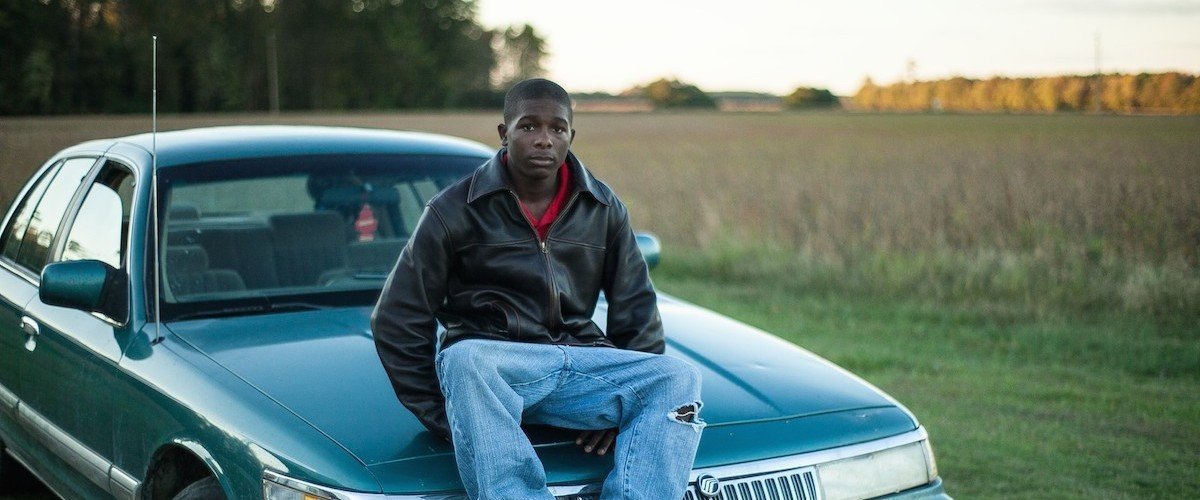

Junior has a great smile that, in a flash, can turn into a grimace. David (“Bud”) is a generally good-natured young man with a volatile temper. He works with his dad, who runs a landscaping business tending to the big houses on the wealthier side of town, and he also drives a tractor in the cotton fields. Davonte (“DaDa,” pronounced with long A's) is a quiet fellow who wants be a barber.

At the outset, Junior says something that gives us an idea of how innocent he is —how he's just a kid—but also of of the adult, ugly realities he faces. He says that when he grows up he wants to be rich, so he thought about selling drugs. However, he never really wanted to; plus, his mother says she'll whup him. So maybe he'll just be a "secret agent." (Or, failing that, a mechanic.) He likes living in Bertie and "smelling the corn."

Bertie's population is 80% black. There's not a lot to do for work or recreation. There are, however, a lot of opportunities to get into trouble. As a title advises, there are 27 prisons within a 100-mile radius of Bertie County. In fact, DaDa's brother, who boasts the memorable sobriquet "Mickey Mouse," is locked up. His brother is, DaDa admits, something of a kingpin among local drug dealers. DaDa and his mom, Esther, care for Mickey Mouse's baby while he's in jail.

DaDa, Bud and Junior attend an alternative high school called the Hive, expressly set up to meet the needs of black boys. Vivian Saunders, the kindly executive director, wants to pull suspended boys off the streets and back into the school system, while giving them the "love and caring" they don't get there. "I tell them they can be educated at the Hive or be educated in jail," says Saunders. While DaDa is bright—he has a nice ironic sense of humor—he's always required extra time for his schoolwork. The Hive makes him feel like he can learn. When the school board shuts the Hive down, the boys awkwardly integrate into the official Bertie High. Saunders worries, have we given them the tools to survive without getting in trouble? She offers an interesting analysis of the role of violence in these young men's lives: "It goes back to being a tenant farmer," she says. "They have to prove themselves through violence and joining gangs."

The violence seems to spring, as well, from a fierce disinclination to be looked down upon—to be "disrespected."

Violence can be passed down. Junior's mom Cheryl is a survivor of domestic violence at the hands of Junior's dad, who went on to murder a subsequent girlfriend (and a deputy). One of the movie's most heartbreaking scene is the one where Junior visits him in prison. Even Bud's dad, the hardworking landscape architect, beat him until he "peed himself," according to Bud, as a method of discipline.

Seen in the background in a shot at Bertie High School is a banner reading, "Children learn what they live."

Cheryl, Junior's mom, works three jobs, yet she still eventually loses the house. Esther, Dada's mom, is estranged from his dad, Ernest, who comes off as a rather self-centered man with a drinking problem. Movingly, DaDa still yearns for his approval and attention. Veronica, Bud's mom, is a cherubic, religious woman who works at the chicken processing plant.

RAISING BERTIE begins its run on June 16 at Black World Cinema at the Studio Movie Grill Chatham (210 87th St.) – Check the venue website for showtimes. The filmmakers will be in person at the weekend screenings.

Reader Comments