The Harvest

Karolyn and I popped over to the 49th Chicago International Film Festival and caught the world premiere of “The Harvest,” the latest work from two Chicago guys, actor Michael Shannon and director John McNaughton. It’s a psychological story. By that I mean it's about the relationships between the characters, but the funny thing is, you won't get the true meaning of the glances and words, the actions and shifting loyalties, except in hindsight or on a second viewing. Writing about this one depends more than usual on not giving too much away. Suffice it to say that the writer, Stephen Lancellotti, who attended our screening, has created a story with (urban) mythic resonance. It's all pretty implausible, probably, but if we learned anything from Hitchcock it's that we probably shouldn't worry too much about plausibility, at least in the movies. (And you won't if you had fun with McNaughton's last picture, 1998's "Wild Things," which I did.)

We meet Katherine (Samantha Morton) when she pulls down her surgeon’s mask. She’s just saved a boy’s life: he was hit in the chest by a well-hit baseball. Her own son, prepubescent Andy (Charlie Tahan) is gravely ill. A frail, bedbound boy, he can barely lift himself from his wheelchair to his bed, whence he watches the cornstalks grow just outside his window. His mother has charged him with guarding “his” harvest, and so he watches for crows, rapping on the window to ward them off. She homeschools him and pretty much keeps him cut off from the outside world. She even discourages him from trying to walk on his own.

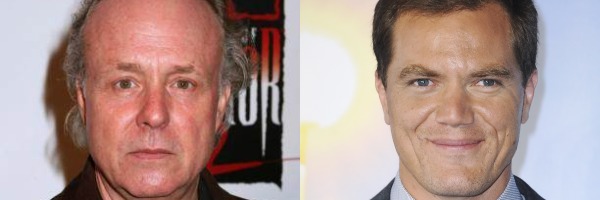

Shannon plays Richard, Katherine’s husband. He’s kind of a big kid himself: a bit slow maybe, with his big furrowed brow, but not without a mordant humor, his eyes sad, lip softly bit as if biting back an interior life. Something in his psychological makeup allows him to go along with Katherine, but only up to a certain point: he gives her pushback about her zealous overprotection. For her part, while she's the steely boss, she can break and be needy by turns.

Through Andy’s window comes bold, intrepid Maryann (young Natasha Calis, excellent), as if answering the wish for a friend he didn’t know he had. She lives just through the woods with her grandparents (Leslie Lyles and a moving Peter Fonda). She’s just moved to town, still raw from her parents' death in a car accident. She is a girl of action, and pretty soon she’s sneaking him outside to play.

Katherine regards Maryann with a look so icy it’s like being under a mile of frozen ground. But why? Maryann’s company is so obviously good for Andy. Is it jealousy? Before long Maryann is playing detective. Of course, nobody will listen to her about what she’s discovered (she's just a kid, after all, although Fonda does get off a good “groovy”), and I won't tell you here, except it's not good.

A more expressive director than McNaughton might have pushed this material into horror or melodrama or even camp (which is where he took his "Wild Things," come to think of it), but his unexploitative, relatively flat style here allows the story to remain in the realm of the psychological, though shading into horror. Like the film itself, Morton’s Katherine inhabits some twilight between psychological thriller and horror movie. She evokes iconic performances like Louise Fletcher’s Nurse Ratched in “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” Piper Laurie as Carrie’s mom, Kathy Bates in “Misery,” and Faye Dunaway as “Mommie Dearest.” Isn’t there something a bit sexist by now, you might ask, about this trope: a maternal power whom the rebel (often a man) must fight? Maybe, but here it’s balanced by brave Maryann’s girl power.

At the question and answer session, Shannon, generally laconic in temperament, declared that “The Harvest” is about love. Really about love, he stressed, not like some Ryan Reynolds/Rachel McAdams movie that "I would probably hate.” (Now, I happen to think Rachel McAdams is a doll, but that's me.) It’s a love gone horribly awry, but still: it's about a mother's love. I suspect this is what is what Morton latched onto to play Katherine, to make her pathetic as well as scary. There are moments when we actually sympathize with her, and it's because of this mad love, as well as the cosmic unfairness of it all (which is maybe what's driven her mad): she has the power to save other children’s lives, but not her own.

Rating: ***

Key to ratings:

***** (essential viewing)

**** (excellent)

*** (worth a look)

** (forgettable)

* (rubbish!!)

--November 18, 2013

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer

Reader Comments (1)

Neat to be able to attend the 49th Film Festival and see the world premiere of a film by two Chicago guys. The Q & A session with Shannon sounds so interesting. Thanks for the great review!