56 Up

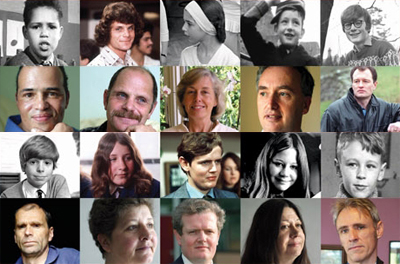

It sounds odd to say so, but I recently went to a family reunion of sorts—at a movie theater. I mean to say I saw “56 Up,” the latest episode in Michael Apted’s Up Series. In 1964 a handful of British seven-year-olds from different backgrounds were asked, on camera, their views on life. Originally the program’s point was to see if the seismic shifts of the sixties meant changes for Britain’s class system as well.

We check back in with them every seven years. Those kids we saw dancing happily to the new beat music at the end of “7 Up” are now 56. For the most part, they have had a strong foundation when the winds of changes shift.

Funny, when you watch the Up movies you’re also watching yourself, in a way. In 1999, Apted filmed the Uppers at age 42. Since I’ve now arrived at that age myself, I watched the clips from “42” folded into “56” with renewed interest.

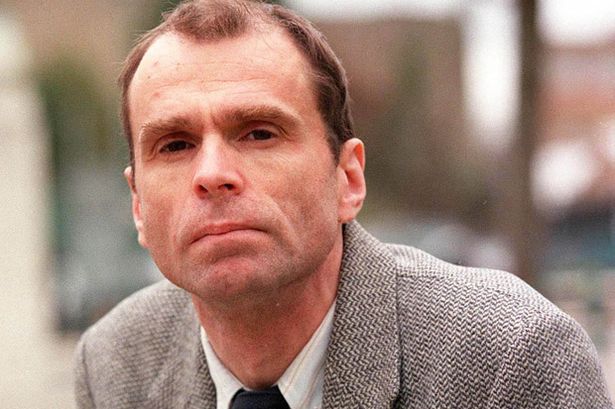

When the Uppers were younger, there were great changes every seven years. There are fewer surprises now. At 56, they’ve settled in; their personalities are fully formed. Yet they’re still trying new things. One surprise: Peter is back. He bowed out after his sarcastic comments about Thatcher-era Britain got him into trouble in “28” back in 1985. Now he’s back, mainly to build a wider audience for his Americana band, The Good Intentions.

The Up Series is about the moments that make up a life. I think of Tony the cabbie, the East End kid who wanted to be a jockey, and who once had a “photo finish” in a race against the famous jockey Lester Piggott. I think of Sue in her 30s singing karaoke in a pub: a moment of happiness.

Many of the funniest moments are still from “7,” and we see them again. When asked about girlfriends, Andrew tells the camera that while he does have one, he doesn’t think much of her. Asked a similar question, young Nick, who grew up to teach engineering in Wisconsin, burns the camera down with a look before proclaiming, “I don’t answer questions like that.” (“Still the most sensible answer,” says 21-year-old Nick with a smile.) Seven-year-old John one-ups Andrew: he not only reads the Financial Times, but the Observer as well.

The film’s structure is captured poetically in the famous image of Jackie, Lynn and Sue together, holding a picture of their younger selves gathered around a picture of their younger selves, and so on. (Apted doesn’t gather them together in “56”). Though of course the British feel just as strongly as anyone, the film’s surface, its voice and montage, is too British (i.e., objective, unemotional) to be expressive, exactly. The effect is more like that of the years accumulating softly like snow.

Over the years, one thing the Up Series has become about is love. Words from the poet come to mind. “Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks within his bending sickle's compass come. Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, but bears it out even to the edge of doom.”

As in prior installments, in “56” Andrew is interviewed with his wife, who memorably described herself in her 20s when she said that Andrew hadn’t married a “haughty deb” but a “good Yorkshire lass.” My own baby, Karolyn, got a kick out of Symon’s wife. (She’s strong-willed, high-spirited and good-humored, just like my baby.) Paul is still happy in Australia with his wife of many years.

There’s beautiful footage of the rolling green countryside of Scotland, where we catch up with Jackie, and the dales of North West England, where we find Neil, still representing his village on the council. The years have made Jackie’s face appear a bit sad and tired, but she is unbowed.

Neil is the only one of the Uppers for whom the happy child he once was seems completely lost to him. In fact, the ghost of his childhood is haunting. That’s why it does our hearts good to see that even in his solitude he has found a measure of happiness and community, if not exactly serenity.

As always, we end with the children’s day out in London and the recitation of the Jesuit maxim, “Give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man.”

In his segment of “56,” Paul admits sheepishly that he never had much ambition in life. Maybe what the Up Series finally shows us about life is that it’s not necessarily about that, at the end of the day. It’s about being happy. Lynn grew up to be a librarian and, until her program was cut, read stories to special-needs children. What work could be more important than that?

Once upon a time I had an idea: I thought that the real subject of the Up Series is time. Now I think that it is happiness.

Rating: *****

--March 1, 2013

Key to ratings:

***** (essential viewing)

**** (excellent)

*** (worth a look)

** (forgettable)

* (rubbish!!)

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer