"Boyhood," Richard Linklater's new film, takes just shy of three hours to watch, yet it took 12 years to make. It unspools 12 years in the life of an American boy named Mason. His life is very similar to the life of any American boy, myself included. To portray Mason the filmmakers rolled the dice and picked young Ellar Coltrane, who was six years old when he was brought into the project in 2002; when filming concluded in 2013, he was 18. With "Boyhood" we now have a time capsule of life as it was lived in the United States in the "aughts," the first decade of this century. These were the tumultuous post-9/11 years, the Bush years into the Obama era.

Linklater is one of my main men. I go way back with him. I remember seeing "Slacker," his first feature, in a theater back in 1991, up in the balcony at the Athena in my hometown, Athens, Ohio. I admire this movie tremendously, even if I can't say I love it the way I love his three "Before" films, which are in my personal pantheon. "Boyhood" is a film of privileged moments, and even if fewer of those moments are magical than in the "Before" movies, enough of them are. It complements them beautifully in its elegant elision of his central theme, the passage of time. For Linklater, movies are a time machine. His is a cinema of memory and beauty.

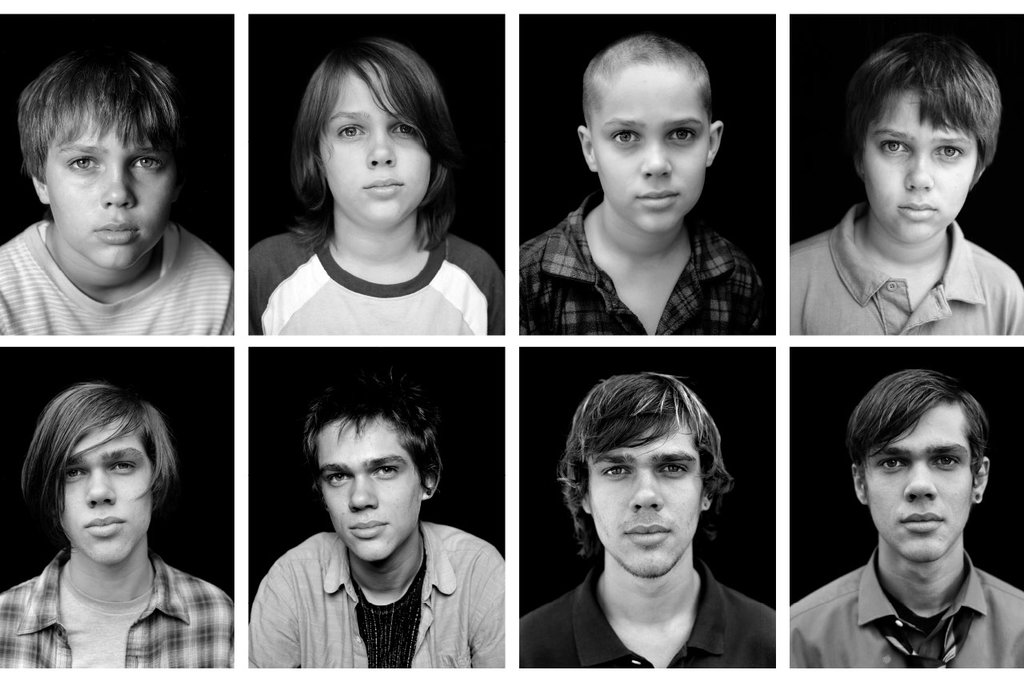

We flow on a rushing river of time as its eddies and currents form and sculpt Mason's features. These changes would be imperceptible In the space of years; in the space of this movie they are striking. Facial features form and grow before our eyes. This has a certain effect: you can see the little boy or little girl in the young man or woman. Thus, we get a sense, perhaps, of why parents always see their kids as kids on some level, no matter how big they get. A parent always sees the palimpsest of the past in the present.

The movie is a river of experiences, some male, some generational, some universal. Riding bikes. (And is there anything more emblematic of childhood than riding bikes?) Pouring over girlie magazines excitedly with schoolyard chums. Encountering bullies, and being surprised to learn how pointlessly, stupidly mean people can be. Lining up in costume at midnight to get the new Harry Potter book. Having a first taste of beer as an eighth grader. With some movies we say we've seen this before: with "Boyhood," we say we've lived it before.

Patricia Arquette and Ethan Hawke are credited as "mom" and "dad." (Their names are Olivia and Mason, Sr., but this story is from Mason's point of view.) They were really young when they had kids. Now they are separated, and she is a single mom. When Mason asks mom during bedtime story if she still loves dad, she answers that yes, she still loves his father: they just weren't good for each other. One of the ideas the film plays with is the question of whether boys ever really grow up. Certainly dad is still kind of a kid when we first meet him, a searcher, self-involved, cocky. When he's done wandering he finds himself quite capable of swooping into their lives in his black GTO and being "fun dad," taking them out for bowling night.

Linklater's achievement with "Boyhood" is to synthesize the dramatic fictional film and the documentary. I think of the scene where our fictional characters--dad, Mason, and Mason's sister Samantha (played by Lorelei Linklater, the director's daughter)--go to a real baseball game. It's kind of fascinating to think about. Here we have a fictional story merging with documentary footage of an exciting Houston Astros game.

The "Up" series of documentaries, which I love, which in fact move me perhaps more than any other films, also returned to its people across many years. The difference is that "Boyhood" is acted, scripted and, well, fiction. At the same time, the film can't help but record 12 years of changes to Ellar Coltrane, not just Mason. Hair lengths and colors change.

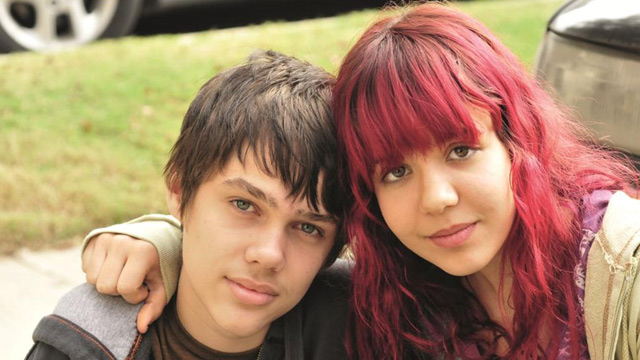

Technology changes. Mason works on a huge monitor as a grade schooler; by the end of high school he lives in the iPhone era. He's skeptical. Are we really "in the moment" if we're always staring at a little iPhone screen, he wonders? His high-school girlfriend, Sheena (Zoe Graham), is optimistic. It's just a tool to connect me with my friends, she says.

(While we are not privy, mercifully, to Mason's first sexual experience, we do wake him and Sheena up in bed one morning. Samantha had let them use her dorm room, but her roommate comes home unexpectedly and discovers them under covers. Embarrassment all around.)

What "Boyhood" does have in common with the "Up" series is the way it plays you as you play it, so that as you watch a scene recorded in a specific moment in time, you reflect on what you were doing in your own life at that moment. For some reason this feeling was most acute for me when we see Mason and dad hiking through the woods on a camping trip in summer 2008. Likewise, each experience Mason undergoes causes you to think about what your turn with the same experience was like.

This soundtrack is a time capsule as well. We begin with a little Coldplay and "Yellow" as six-year-old Mason lies on the grass and gazes up at the sky. Along the way we get the Flaming Lips' “Do You Realize??", Family of the Year's beautifully aching song "Hero," Arcade Fire's "Deep Blue" in the movie's final stretches. We know from our own lives that these songs will always take Mason back to the specific time and place when he first heard them.

I will say, I sure must have been in a different place (like, not deep in the cut in the clubs) when "Good Girls Gone Bad" by Cobra Starship dropped. I never heard that one in my life, yet it's meant to be emblematic of 2009. Kinda catchy. On the other hand, my baby Karolyn tells me that "Crank That" by Soulja Boy, meant to cue 2007, and which I somehow also missed, is her jam!

Much more to my taste are dad's jams. (That makes sense, since we're the same age, 40-somethings.) In fact, the music he likes is the same music I was listening to during those years. He plays his son Wilco's "Sky Blue Sky" in the car, passionately explaining why it's so great. I was listening to that very album n 2007. As we hear Jeff Tweedy sing "Hate it Here" ("I try to stay busy, I do the dishes, I mow the lawn"), dad's pedantic commentary bemuses his son. See, it's just basic country, listen to that, he enthuses. And the production! It's like "Abbey Road" or something! (Actually Tweedy wrote Linklater a lovely, modest new song for the movie, "Summer Noon," which we hear on the end credits.) Dad is listening to Dylan's "Beyond the Horizon" from 2006's "Modern Times" as the minivan pulls away with his new wife (Jenni Tooley) and baby in back. I had that album in heavy rotation that year myself.

For Mason's birthday one year dad makes the boy a mix CD. He has titled it "The Black Album." It contains music by the solo Beatles, and dad proclaims he has edited the album conceptually so that it works as a dialogue/debate between the individual Fab Four philosophies. You can tell he worked really hard on it. It's a labor of love. He doesn't say so, but we can see he feels it is his fatherly duty to pass on the secrets and truths of rock 'n' roll, that having this music in your life will make your life happier, that in fact all of life is in this music. All things must pass, as George told. Which could be the secret title of this movie.

Essentially, what Linklater and his crew did was make a short film every year. One could almost view "Boyhood" as a series of discrete short films, seamlessly interwoven. The most memorable might be the one that tells the story of mom's marriage to her college professor. He has kids, and the two families merge. Gradually, not overnight, he becomes a monster. We see that he is in the habit of hiding hard liquor around the house. Marco Perella is excellent as this martinet: cruel, capricious, arbitrary. Yet he's not always that way: sometimes he can be fun and funny, if always quick with a taunt. The family has largely figured out ways to enable and appease and humor him. Mom is a bit preoccupied, always studying, trying to become a professor herself. After he takes his outbursts to a new level of violence the kids hide out together, bunkering down in a bedroom, and Mason is comforted by watching a Will Ferrell video over and over.

This is one childhood experience I am glad to say I do not share with Mason. I can only imagine how terrifying it must be to be in an abusive home, with some all-powerful giant lumbering around, liable to snap at any moment. I won't forget the scene where the kids roll up on their bikes and see their mother on the garage floor. The garage door is half down, obscuring our view so all we see of the professor is his legs swaying above her on the steps as we hear him bellowing. She shrieks at the kids to run away.

I also can't forget the way Linklater framed the shot of the kids arrayed along the couch as dad interrogates them about whether or not they've been in contact with their mother, checking each kid's phone and then chucking it back at him or her, except for his own daughter. "I trust you," he tells her, and there passes a look between them that makes us wonder what else is going on there, and how screwed up she's going to be. Thankfully mom gets her kids away from that house before he ever really does more than emotional violence to them.

Through it all, dad still swoops up in that black GTO, whisking them off for fun times. Actually Mason and Samantha feel calm when the sleep over at the apartment dad shares with his musician pal, Jimmy (played by Charlie Sexton, whom we know as Bob Dylan's guitar man). Funnily enough, the rock & roll crash pad is actually a welcome sanctuary for the kids, offering stability, even adult responsibility, they don't get at home.

Some of my favorite privileged moments in the film are when dad plays his guitar for the kids. Not because the songs are all that great: they're humble. But he wrote them for the kids and they're an expression of love. One of these moments is in a tent in the woods, one is on grandma and grandpa's porch, with the teenage kids and new wife gamely singing along to the choruses. Dad had hoped to be a musician we watch that dream recede over the years, as he goes deeper into the insurance industry. Not that he ever seems sad or bitter about it, really. We all know that's what life can do. When his son says "I thought you were a musician," dad replies that he is, but "Life is expensive." As annoyingly feckless as dad was, it's sad when he drops the bombshell that he sold that black GTO he used to swoop up in. (Hurt, Mason sulks, you were going to give that to me when I turned 16.) The feckless young dreamer "grows up."

It's important to note that the people who made "Boyhood" are almost all Texans. The movie was edited by the great Sandra Adair, who has cut all of Linklater's features since "Dazed and Confused" in 1993. Down the years it was photographed by two of Linklater's longtime cinematographers, Shane Kelly ("A Scanner Darkly") and Lee Daniel, who lensed Linklater's films all the way back to "Dazed and Confused." There is something special about the light they get. It is soft, diffuse, warm. A summer light. Sunlight. In close-up, the film glows. The perfect light for privileged moments. I think of the close-ups of Zoe Graham, her hair glowing.

All the "Boyhood" filmmakers were born in Austin or Houston or Dallas (and New Mexico and Mexico too), the land in which the film is set. This is true of Richard Linklater and Ethan Hawke and Ellar Coltrane. Even Charlie Sexton is from San Antonio. (Patricia Arquette, hailing from the great city of Chicago, is an exception). The film is refreshing in the sense that it broadcasts a very natural, multifaceted portrait of Texans, countering stereotypical images.

The filmmakers also make great use of the monumental natural beauty of the American west. When dad drives his GTO out into the great wide open, into the great blue sky and mesas, the feeling of freedom is physical. I think of a hike out to a swimming hole in an arroyo. Gorgeous.

In 2004 scenes of carnage in Iraq play out on a TV in a pizza joint where dad takes Mason and Samantha. He asks the kids who they like for the election. "Anyone but Bush!," he proclaims, is the correct answer. (I remember those days well). The talk morphs into a frank sex talk, with dad discussing birth control openly with adolescent Samantha, who is mortified. She can't stop giggling. Lorelei Linklater is very good here, naked in her embarrassment. Again, we can see dad really does loves the kids.

As 2008 approaches, dad, full of missionary zeal, takes his kids out to knock on doors for Obama. Karolyn and I chuckled as dad urged Mason to yank a McCain sign out of a yard and chuck it in the trunk. (We wouldn't advocate that in real life.) Knocking on a door, Mason meets a crotchety old white fellow who declares, pointedly, do I look like a supporter of Barack Hussein Obama? Mason shrugs. The man foams. You're on private property and I could shoot you! I remember people like that. Samantha knocks on a door and meets an effusive "Obama Mama." I remember them as well. (Frankly, I'm much more comfortable around the latter.)

However, the movie does not let us Blue Staters get too smug about the superiority of our own values. The family goes out target-shooting when they visit grandma and grandpa at Mason's birthday. We observe that dad agrees it's not a bad idea for the kids to learn to handle a firearm. He's still a Texan, even if he rebels against it. For his birthday Mason's grandparents give him not only his first suit, but a bible embossed with his name and a shotgun. While Linklater plays the scene for laughs, the scene is not without affection for the grandparents. He's bemused by these people, but he's still a Texan too, even if one of an avowedly Blue state of mind.

Mason grows into a young man who is introverted, shy, gentle, thoughtful. He becomes a photographer, with real talent. We can see he's got a great eye for texture. One day his high school photography teacher (Tom McTigue) closes himself off in the darkroom with Mason and lectures him about getting serious. I related to this scene, except with me it was my high school band teacher who closed the practice-room door behind himself to have a little heart-to-heart with me, interrupting my pleasant time bashing away on a drum set.

Mom becomes a professor. When she throws a Thanksgiving dinner for students and faculty, she meets a Marine (nicely played by Brad Hawkins), a thoughtful vet who becomes her second husband. Gradually, the man's values of duty and loyalty, which once attracted her, mutate into drunken authoritarianism (again) directed at the the quiet Mason, whom he seems to want to "make a man" out of. Finally this man seems another casualty of the Iraq war, perhaps, pounding beers on the porch in his security guard uniform.

There is a graduation party for Mason. We glimpse the family friend who helped extricate mom from the alcoholic's house years ago. Her little girl is there as well, big now. (She'd taken the family in, for how long we never really know).

Mom and dad run into each other in the kitchen. As far as I can recall, this is the only scene in the 2:45 movie that Ellar Coltrane is not in. They talk. You did a great job raising the kids, he says. He knows he didn't have to do the hard work of raising them. We fought a lot, but if we'd met at different points in our lives, who knows? He offers her money for the party. Perhaps unexpectedly, she accepts. Turns out he doesn't have any cash on him, but he'll hit an ATM. It's a bit embarrassing for both.

While there are no big actorly moments for anyone in this movie, no one is less than natural throughout. It's an achievement, sustaining a continuity of a performance over 12 years. Hats off to Hawke, Arquette and young Mr. Coltrane.

As the day draws near when Mason is to leave for college draws near, mom has a small breakdown. As the movie ends she seems like the character least headed for a happy life. This movie has mainly been about the male experience, with only tangential looks at the female experience.

In their final scene together, Mason and his dad have a heart-to-heart at a bar. He's broken up with Sheena. He thought he'd made a real connection, and he needs some advice. At first I found the scene unsatisfying. Dad's advice about the breakup is not all that great, or even wise. As a bonding moment it left something to be desired. Then I realized the talk must have been unsatisfying for Mason as well. And then I realized that the scene is really about that moment when kids see a truth about older generations: they're actually still figuring it all out, too. Adults are not all-knowing. They have much more experience, true, but to a certain extent they're still winging it. You will never really get to a point where you're not. Dad is honest about that here. All it means, really, is that you realize you have to figure it out for yourself, on your own terms. That's growing up.

We leave Mason hiking in the canyons with his new college friends. He falls into conversation with a nice girl. The kids have ingested something allegedly psychedelic as the sun sets, but it doesn't really seem to do all that much, but that's okay, really, because the world itself is glorious. And as his new crazy roommate howls with joy at the beauty of this moment out in the desert, Mason is a young man on the doorstep of life. He is 18 years old. He has a strong foundation. He is as ready as he will ever be for the whole life that is in front of him. As ready as any of us ever are.

Rating: ****1/2

Key to ratings:

***** (essential viewing)

**** (excellent)

*** (worth a look)

** (forgettable)

* (rubbish!!)

no stars (utter shite)

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Friday, December 5, 2014 at 05:15PM

Friday, December 5, 2014 at 05:15PM