There was some bravura filmmaking in 2014. Whatever the fireworks of other films, though, for me the movie of the year, hands down, had to be the Roger Ebert documentary, Life Itself. I've written a lot about what Ebert meant to me, here and here, and elsewhere. I will say it again: Roger Ebert, on television and in print, made me aware of movies as an art form.

Speaking of life itself, 2014 was the year I married the love of my life, my beautiful baby, Karolyn. Ours was a mid-life marriage, like Roger's and Chaz Ebert's (another reason Life Itself had to be my movie of the year). While I love film, and try to see as much as I can, this year life itself took priority. Watching films comes in a distant second for me to traveling with my baby, or snuggling with my baby. The best of all worlds, of course? Streaming one of my Criterions as my baby snuggles up and falls asleep with her head on my shoulder.

That is because in my life film is a place: a place I like to go. It could be a place in memory. Some movies contain old friends, and we enter the movie's world as a way of visiting with them. Ebert wrote about how some movies are so absorbing that the awareness we're watching a movie falls away. Certain films this year, like Wild, felt like that.

I don't watch films full-time, as I say. I therefore must give a shout-out to all the interesting projects that were not considered for this list, simply because life itself happened and I didn't see them by press-time. The roll call, please:

Interstellar; Starred Up; Foxcatcher; Fury; Nightcrawler; Gone Girl; The Trip to Italy; Memphis; Listen Up, Philip; Ida; Citizenfour; 20,000 Days on Earth; Frank; Calvary; Force Majeure; Dear White People; The Babadook; The Tale of the Princess Kaguya; Captain America: The Winter Soldier; Mommy; This Afternoon; St. Vincent; Still Alice; Beyond the Lights; Inherent Vice (the current release that most interests me); Selma; Mr. Turner; White God; Low Down; Mistaken for Strangers; The One I Love; Goodbye to Language (this was the 2014 film I most longed to see --3D Godard!--yet it never played Chicago), and on and on.

Look for these! I know I will be. Here, then, is my list of 10 favorite chosen from what I did manage to see in 2014.

1. Life Itself

2014 was a year of thinking about Roger Ebert's legacy. I saw this film twice, and I took a summer class which was devoted to remembering Roger through watching some of his favorite films. This seemed right: I believe that, like all great critics, Ebert will be remembered for what he loved, not what he hated. I have come to believe, after much reflection, that part of what made Ebert such a great critic is that he brought more empathy to his viewing of a film than just about anyone else. And awe, and wonder, and openness to mystery and beauty. Chicago filmmaker Steve James, who gave us Chicago stories like Hoop Dreams and The Interrupters, adds another unforgettable portrait of Chicago life to his oeuvre. In Life Itself we see Roger bearing his final ordeal with stunning grace and even humor, lifted up by the love and the bravery of the extraordinary Chaz. This one was personal for me on a whole lot of levels. I think of the scene at the Alfred Caldwell Lily Pond. Roger loved to walk, and this was one of his favorite places. I discovered it thanks to him, and Karolyn and I staged some of our wedding photographs there in part in homage to Roger (it was her beautiful idea, I should add.) "Life Itself" was our favorite love story of the year. In our discussions afterwords, the words we used to express this were the words we both were thinking during the film: "You're my Chaz" and "You're my Roger."

2. Boyhood

Life in Texas, as it was lived during the first decade of our century. Richard Linklater filmed the picture over these last 12 years. Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette were mom and dad; Ellar Coltrane was the boy. No plot machinery, just an accumulation of incident that added up to a childhood, such as weathering an abusive, tyrannical, alcoholic stepdad. We flow on a river of experiences, some male, some generational, some universal. (Is there anything more emblematic of childhood than riding bikes?) Linklater is one of my favorite directors, and with "Boyhood" he had synthesized the fictional film and the documentary. Film as an unspooling ribbon of time and memory. The river's eddies and currents form and sculpt Mason's features before our eyes. When, finally, we look upon the visage of the young man, we see the palimpsest of the little boy, the past in the present.

3. Birdman or The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance

This was the most bravura piece of cinema I saw this year on a formal level: it creates the illusion that it is composed almost entirely of one single, sustained, headlong tracking shot. Aside from being the year's best treatment of space, this is also a joyful film about escaping the prison of the self. Alejandro González Iñárritu takes his place amongst the great humanitarian directors. I've never read the Raymond Carver story, "What We Talk ABout When We Talk about Love," but I'd wager the key to the mystery of that subtitle is in the story. Iñárritu's pictures are about people standing at a precipice: we meet them at that moment when the must decide whether they are going to live or whether they are going to die. They are also about the life-force that courses through us all. Michael Keaton plays a man who, much like himself, starred in comic-book movies some 25 years ago, and now burns to create something with meaning, something honest and true. Pungent script written by Iñárritu with Alexander Dinelaris, Nicolás Giacobone, and Armando Bo.

4. Wild

After we walked out of this film, both with tear-streaked faces, I turned to Karolyn and said, "There are certain movies I wish Roger could see, and that is one of them." And Karolyn looked at me and said something really beautiful. "Are you kidding?" she said. "He's seeing them, all right. Where he is, he's even helping make them, at this point." "Wild" is a story about death and rebirth. Reese Witherspoon is Cheryl Strayed, carrying her baggage, literally and metaphorically, along the Pacific Crest Trail in the wake of the untimely death of her young mother (Laura Dern, never better) and her subsequent spinout. 2014 was also a year of reading Kerouac for me, and this film was a compliment to my reading, both in spirit and because the Pacific Crest Trail traverses Kerouac's Pacific Northwest stomping grounds like Matterhorn Peak in Yosemite National Park and Desolation Peak in the Cascades, places I visited in books like "The Dharma Bums." This movie has a deep, non-moralistic faith in humanity. It's a movie about love and hope.

5. Whiplash

The year's most intense movie experience. I kept thinking of the dreamy reverie of Lou Reed's "Coney Island Baby": "When I was a young man in high school, you know I wanted to play football for the coach...they all said he was mean and cruel, but he was the straightest dude I ever knew." "Whiplash" is about that impulse to live up to the standard of an exacting mentor. J.K. Simmons is Fletcher, the great, scary jazz teacher. He's mean and cruel, all right, but the twist is, he's one crooked dude as well. Stunning performance from Simmons; stunning filmmaking from Damien Chazelle. Tom Cross, the film's editor, should be seen as a kind of musician himself. Miles Teller is the young drummer paying the cost to be the best, in sweat and blood.

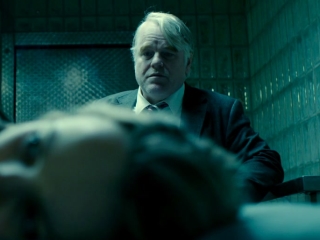

6. A Most Wanted Man

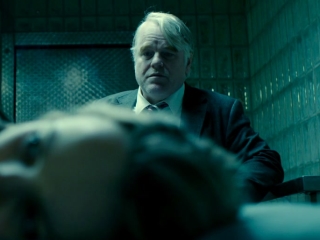

A haunting, absorbing spy story about young Muslim man (Grigoriy Dobrygin) who emerges from a canal in post-9/11 Hamburg, presenting himself as a refugee from torture in Turkey, and who ends up pushed into the spaces between "dirty" and "clean," presumably to disappear into some secret C.I.A. detention center to face torture. A human rights lawyer (Rachel McAdams, watchful) takes him under her wing, but can she trust what she feels? In a spy movie, of couse, everybody is performing. The Americans see the world in black and white, while the Germans, led by Philip Seymour Hoffman, see shades of gray. A chilling Robin Wright embodies the Bush administration's stubborn, almost cheerfully unapologetic view of a world divided into good and evil, a view that doesn't only murder nuance, but people as well. Anton Corbijn, the director, is known for his imagery for U2 and Tom Waits and the the lustrous Joy Division/Ian Curtis biopic, "Control." Adapted by Andrew Bovell from the novel by John le Carre. As the sad-eyed German agent, the late, great Hoffman imbues the picture with real despair. Written on his face is guilt and tragedy, Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib and the Twin Towers. In its quiet way, "A Most Wanted Man" may be the movie that says the most about the Bush years.

7. The Imitation Game

This one is still fresh for me, but even if I haven't quite sorted out my thoughts about it, I know how it made me feel. It's funny. When you play back this film in your mind, you can see that it's rather pat. It does not play that way as you're watching it, though. The story is deeply absorbing, the performances soulful and true. Whatever its simplifications, from scene to scene as acted it plays as very emotionally complex. The film tells the true story of Alan Turing, adapted, with many liberties taken for the sake of making an entertaining movie, by Graham Moore from Andrews Hodges's book. Turing was a mathematician who found the codes of basic social interaction almost impenetrable, but, precisely because his brain did work like a computer, was able to build a machine that cracked Enigma, the Nazis' cipher machine that broadcast their secret war plans. Yet his tragedy was that he was undone by his very human urges. (This was a time when homosexual acts were illegal). Heartbreaking performance by Benedict Cumberbatch. The pleasurable and sad subtext of this kind of intelligent, witty British production is that there was tremendous pluck and depth of feeling swallowed up under the quiet desperation and stiff upper lip of the English way. Excellent acting by Charles Dance, Mark Strong, Matthew Goode, Keira Knightley, and especially Alex Lawther as the young Turing. An image sticks in the mind: after a German bombing raid, a London woman sits atop the rubble of her home drinking tea. Directed by Morten Tyldum.

8. Love is Strange

Here is a fascinatingly, sometimes frustratingly elliptical glimpse into the lives of Ben (John Lithgow) and George (Alfred Molina), two very dapper gentlemen whom we meet on their wedding day. They have been together for 40 years. It's a truly happy day. There is a wonderfully warm reception: Ben and George sing and play at a box piano, are toasted by family and friends. But by getting married, George has violated his pledge to the religious school where he teaches choral singing, and they fire him. They can no longer make the payments on their elegantly appointed New York apartment, and they must impose on those family and friends. Marisa Tomei is very good as a self-absorbed yet patient novelist whose family hosts Ben. The film has the personality of George (modest, quiet, elegant, classical) and the painterly eye of Ben. Like a painter, the film cherishes light. One of the images that sticks in my mind: a cloud pasted in the blue New York sky, as caught by Ben's eye. Gorgeous piano music (Chopin, Beethoven) fills the soundtrack. Charlie Tahan, the young actor last seen by Karolyn and me in the unreleased "The Harvest," is good as the sullen adolescent who is not thrilled about bunking beds with his Uncle Ben, and with whom Ben shares a little life advice that you know the boy will never forget. Ira Sachs wrote and directed.

9. The Grand Budapest Hotel

Wes Anderson tells of the fictional country of Zubrowka and the once-grand Grand Budapest Hotel, a stately, pastel Beaux Arts building way, way up in the mountains, and the adventures in 1932 of the intrepid lobby boy Zero (Tony Revolori, delightfully deadpan) and the legendary Gustave H., that most gallant of concierges (Ralph Fiennes, perfectly cast). Wes Anderson’s humane intelligence and sense of humor seems to me to be more badly needed with each passing year. It suffuses every striking frame of this comedy. This is minor Anderson, I believe, but minor Anderson is still a thing of many pleasures. He remains our finest children's director.

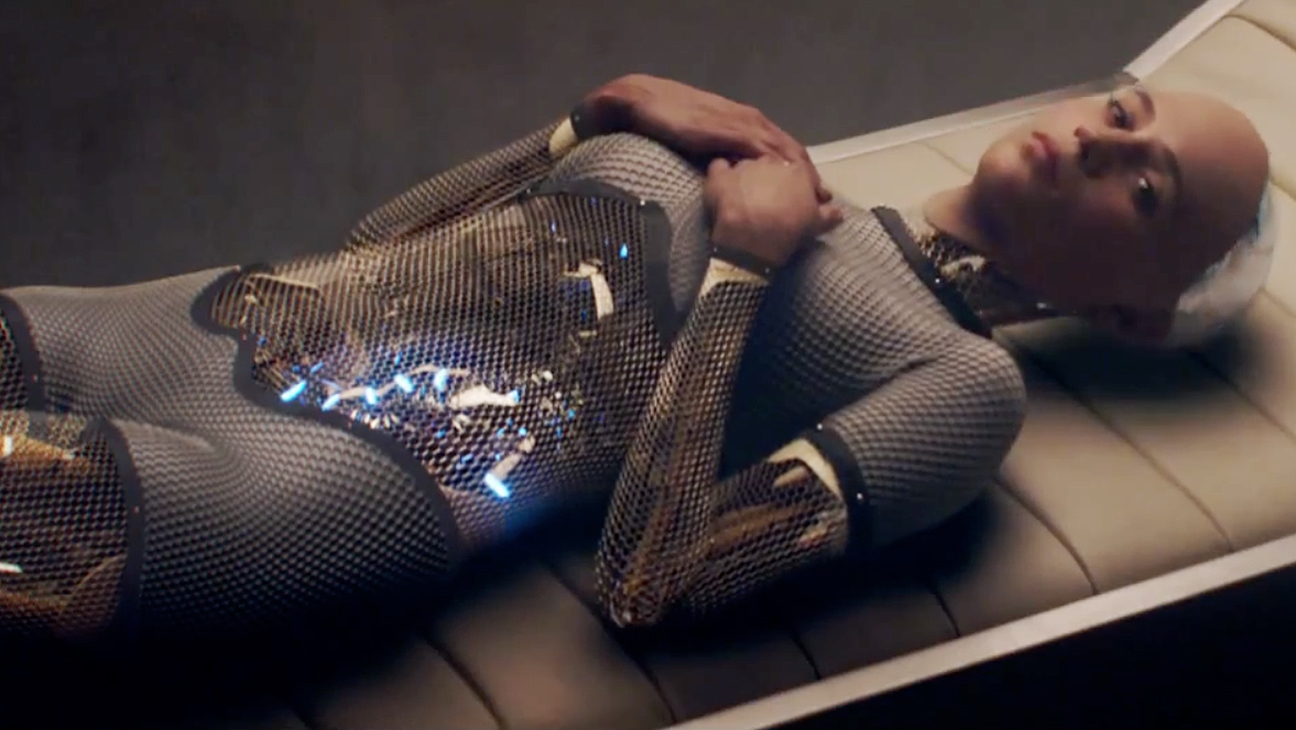

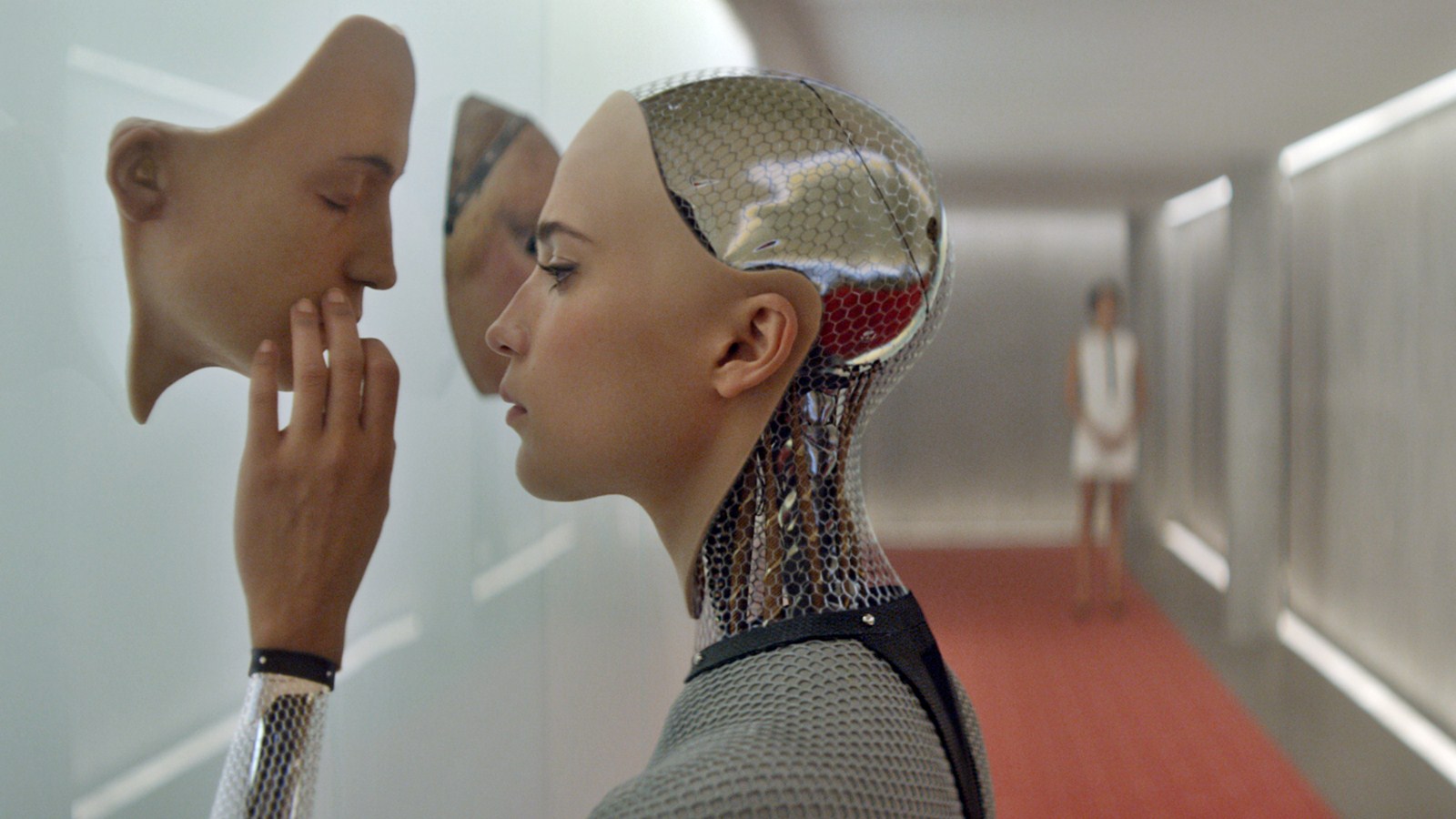

10 Under the Skin

As I've said, this was a year of thinking about Ebert for me, and part of that is visiting him in his writing. I came across his pan of a 1995 picture called "Species," and his review spoke to me as I thought about "Under the Skin." (With Roger, you can learn from the pans as well.) "There is one line in the screenplay," Roger writes of "Species," "that suggests an interesting direction the movie could have taken. Sil, half alien, half human, is driven by instinct, not intelligence, and doesn't know why she acts the way she does. She asks, 'Who am I? What am I?' But the movie never tells her. I can imagine a film in which a creature like Sil struggles with her dual nature, and tries to find self-knowledge. Like Frankenstein's monster, she would be an object of pity." Among many other things, it seems to me that Under the Skin is the picture Ebert was imagining. Scarlett Johanssen plays an alien who comes packaged as a very fetching human female, the better to lure her prey. The film is a storehouse for some of the most strange and original imagery of the year. Directed by Jonathan Glazer from the novel by Michel Faber. One of the things the movie is about is touch: human touch. Unsettling music by violinist Mica Levi skitters under it all. Too rarely are we surprised by a movie: this is one of the rare ones. It's a haunting dream that you can't explain and you can't quite shake.

Honorable mentions:

Obvious Child: This movie felt personal for many women, I understand. Karolyn clued me in to the many, many details I missed as a male viewer. Gillian Robespierre, the writer and director, impresses with her first feature, crude and bittersweet. Featuring Jenny Slate, who found the funny and the tears in a situation, and a decision, that is no laughing matter, and profoundly personal.

Get on Up: Exhilarating biopic of James Brown. Chadwick Boseman hits the slides, sticks the splits, and nails the "no man alive can make me leave this stage" routine.

The Skeleton Twins: "We can make it if we're heart to heart.'

Chef: Cuban rhythms. Cuban sandwiches. Food porn that had Karolyn and me oohing and ahing. Sweet relationship between father and son, and between Jon Favreau and Sofia Vergara as a gracefully divorced couple.

Belle: Deeply felt story directed by Amma Asante featuring a moving turn by Gugu Mbatha-Raw as an 18th-century black woman born into slavery and raised in the family of a prominent British barrister.

22 Jump Street: Laugh-out-loud funny. One of my fondest movie memories of the year: being seized by spasms of helpless laughter with Karolyn at the Davis in the summertime.

The Lego Movie: Everything is awesome!

Blue Ruin: Memorable debut from Jeremy Saulnier about a reluctant, homeless avenger, a novice at violence, who finds himself out of his depths with a vicious family who, when it comes to violence, are fish in water. Vivid colors, sharp sense of rural place and people.

Nymphomanic I and II: The latest from provocateur Lars Von Trier was much more interesting than not. Explicit as all hell, the film was not erotic in the slightest. Quite the opposite, in fact. But it was full of mischief and adult ideas, a dangerous, deeply felt provocation.

Rosewater: Best use of Leonard Cohen next to the the Roger Ebert film: when imprisoned journalist Maziar Bahari (Gael Garcia Bernal) plays Cohen in his mind, he is free. John Stewart, the comedian to whom we increasingly turn for sanity, shows he also has an artist's sense of psychological empathy. He reveals a torturer (Kim Bodnia) as a man who is "just doing his job," with a weary sigh any office worker might recognize.

In Silence ("V tichu") Directed by Zdenek Jiráský, this film from the Czech Republic/Slovakia told the story specifically of the silencing of musicians and dancers and artists by the Holocaust. To make us feel the absence, the film, which is in some ways a "silent" film with score, has opening stretches that convey all the joy of art and life that would be silenced.

Take Me To The River A celebratory film about Memphis music by Martin Shore, featuring Bobby Bland, a lion in winter in his wheelchair, as well as the late Teenie Hodges, "Boo" Mitchell, William Bell, Otis Clay, Snoop Dogg, Charles 'Skip' Pitts, and Booker T. Jones. The film is about passing on a tradition, and it's a joy to see the younger generation, such as the sons of the late, great Memphis music man Jim Dickinson, getting to work with their heroes, handling the legacy of the music they love with such care and concentration. The movie makes a good compliment to Robert Gordon's book, "Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion," which I'm now reading. (Karolyn and I caught this movie at the Chicago International Movies & Music Festival, and Gordon was there to host a Q&A afterwords with some of the musicians featured. William Bell was there, as was, briefly, Booker T. Jones).

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Friday, May 22, 2015 at 05:36PM

Friday, May 22, 2015 at 05:36PM