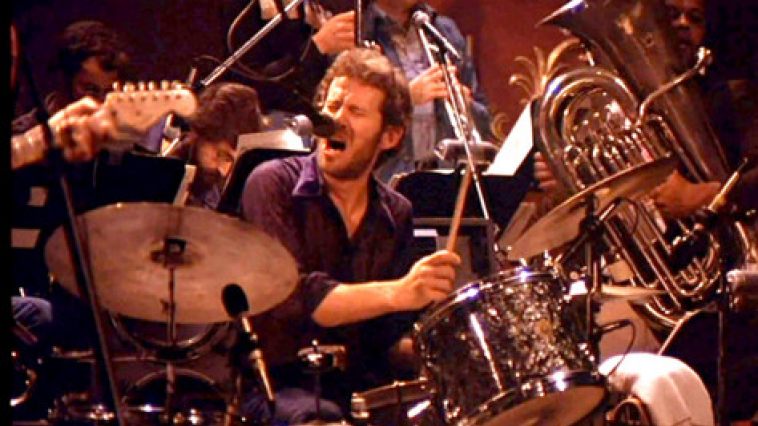

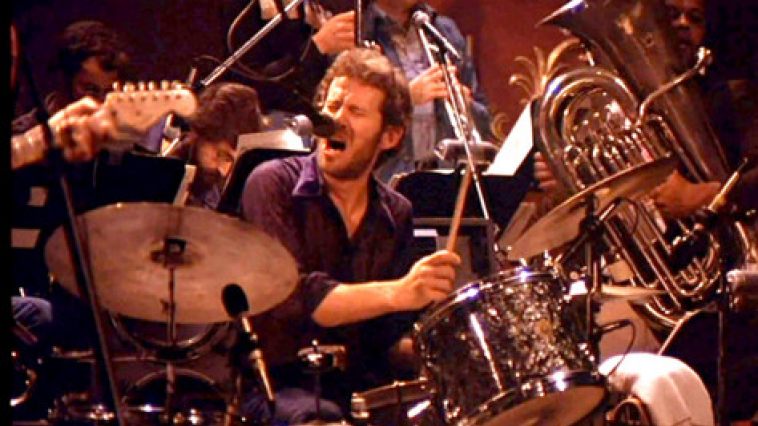

The Last Waltz (on CINE-FILE Chicago)

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Friday, November 11, 2016 at 04:33PM

Friday, November 11, 2016 at 04:33PM I wrote about Martin Scorsese's joyous THE LAST WALTZ for CINE-FILE Chicago. Check it out under the "Also Recommended" section, here.

Martin Scorsese

Martin Scorsese

Did you ever envision the perfect Southern road trip, but weren't sure how to string together the mythic and the real? Then get your hands on a copy of the new hit book by Scott Pfeiffer and Karolyn Steele-Pfeiffer, The Grit, the Grumble, and the Grandeur: Chicago to New Orleans: A Guide to Travel, Food, and Culture. It'll give you the details you need to burn down Highway 61 from Chicago to New Orleans along the Mississippi. Start planning your journey through the Southern past today.

"Again the Beginner," the new album from Al Rose (with notes/comments by yours truly). Available at Bandcamp, Apple Music and Amazon.

If you like the cut of our jib over here at The Moving World, please consider kicking a little something our way.

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Friday, November 11, 2016 at 04:33PM

Friday, November 11, 2016 at 04:33PM I wrote about Martin Scorsese's joyous THE LAST WALTZ for CINE-FILE Chicago. Check it out under the "Also Recommended" section, here.

Martin Scorsese

Martin Scorsese  Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Sunday, October 30, 2016 at 03:59PM

Sunday, October 30, 2016 at 03:59PM I recommended Alice Winocour's DISORDER over at CINE-FILE Chicago. You may read my capsule review, here.

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Friday, October 28, 2016 at 11:25AM

Friday, October 28, 2016 at 11:25AM

In a recent issue of The New Yorker, critic Emily Nussbaum, writing about the TV show Atlanta, observed, "Black masculinity is a set of poses that everyone imitates, including black men." Barry Jenkins' lyrical, sensual drama Moonlight, the best American film I've seen this year, plays a bit like the embodiment of that idea, or like a bell hooks treatise on the patriarchy transformed into drama. And yet it as far removed from a thesis film as can be. No, its acting and writing are far too natural and alive for that. This is a work of art, and a great one. Three chapters trace the identity formation of a shy, gay male at ages nine, 16 and 26, growing up bullied amidst Miami's deadly drug economy. Male tenderness is a casualty of the burden of maintaining the masculine front. Jenkins based his screenplay upon Tarell Alvin McCraney's play, In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue, and the movie's palette, as rendered by cinematographer James Laxton, is as evocative of the beauty of bodies and nature as that title.

There is a moment in the first chapter, entitled "Little," when the awkward nine-year-old boy (Alex Hibbert), whose real name is Chiron but whom everyone calls by that titular sobriquet, asks a man what the word "faggot" means. The man, Juan (Mahershala Ali), is the neighborhood kingpin, a drug dealer who found the abused, neglected Little in one of his "dope holes," taking refuge from bullies. (Little's friend Kevin occasionally tries to toughen him up by teaching him to fight, but it never takes). We might expect we know how he will respond: a faggot is a weak man, a punk. Instead, he carefully explains that "faggot" is a word used to make gay people feel bad. When the boy then asks him if he sells drugs, Juan hesitates. He doesn't want to let Little down--he's become his father figure (just as, as the film progresses, his kind girlfriend Teresa, played by Janelle Monáe, becomes a mother of sorts). Finally, he answers honestly, and Ali makes us feel Juan's shame. We get the sense that while "drug dealer" is the role he ended up playing, it's not "him." Never once does he teach Little to be strong and violent. Quite the opposite: he drops the "hard" mask and shows him vulnerability and love.

Little's actual mother, Paula (Naomie Harris), is addicted to the very crack Juan sells. This role--the crack-addicted mother--could have been a cliché. However, as with every character in the film, Paula is granted her full humanity. In Harris' hands, she is a woman with an illness. During a confrontation with Juan in the street while high, she rhetorically asks him to guess why they bully Little, executing a mocking, limp-wristed caricature of her own prepubescent son. It's scary, heartless. She's got the devil in her eyes. From Little's point of view, she sometimes appears as something out of a horror movie.

In the second chapter, "Chiron," it is seven years later, and the skinny 16-year-old is played with haunted eyes by Chicago's own Ashton Sanders. Juan is dead, we learn. Chiron is still bullied, particularly ruthlessly by one tormentor. Paula has gotten worse. Stumbling towards him one morning, she looks like a zombie, and we'd be surprised if she lived another day.

Kevin is played as a teenager by Jharrel Jerome in a very funny performance, spewing out a rap about his sexual conquests that's so over-the-top and sexist that you just about know he's overcompensating for something. He's always calling Chiron "Black," a nickname the latter doesn't much like. On the beach, they blaze a "J" and talk about how good it feels when a breeze from the water blows through the hood. In a moment that surprises both of them, Kevin, the big-talking ladykiller, gives Chiron his first sexual experience. Afterwards, there's no shame, no regrets. We see a spark of hope in Chiron's eyes. Unfortunately, his chief tormentor at school divines their secret. This ringleader orders Kevin to declare his allegiance--sexually, politically--by beating up Chiron in the schoolyard. In a humiliating, heartbreaking scene, Kevin repeatedly hits an unresisting Chiron, as hands that gave private pleasure inflict public pain. Gentle Chiron keeps getting back up ("stay down," Kevin implores). Later, in a fateful tracking shot, we follow Chiron as he stalks the school corridor, on his way to performing the act that will end this chapter of his life: barging into a classroom and sucker-smashing a chair over the ringleader's back.

In the movie's third act, "Black," Chiron is not little anymore. He's 26, and even his muscles have muscles. The boy has grown up to be a drug boss with a gold grille. Calling himself "Black," adopting Kevin's once-shunned nickname, he's finally performing the pose of masculinity. At first we don't even recognize him. Then the actor, Trevante Rhodes, does something remarkable: he makes you see the scared, scarred, quiet boy in this big, ripped man. In a moving scene, he visits Paula in a rehab clinic. Her demons finally seem quiet.

Then, out of the blue, Kevin (André Holland), calls to offer a meandering apology for what happened 10 years before. He's a cook now, he says. Later, Black gets in his car and drives all night to surprise Kevin at the diner. These final scenes, in which Kevin feeds Black and then takes him back to his home, are so alive with risk, laughter, relief, and regret, that I can only describe them as being touched by grace. Kevin, we see, is now a truly happy man, having dropped the front himself years ago. He's deeply content with his modest, workaday life. He's survived some rough patches. He calls Black out on the whole pose he's affected, and, while Black says very little--he was always shy--we can see him thinking, imagining. In the quiet way he regards Kevin, his eyes speak volumes, and what they say is this: I loved you, even though you hurt me. And: this isn't me. It was never me. Our gentle Little is still there. He's just buried beneath layers of hurt.

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Thursday, October 20, 2016 at 07:07PM

Thursday, October 20, 2016 at 07:07PM

After sampling some of the fare on offer at the moveable feast that is the second week of the 52nd Chicago Film Festival, I would point you toward the following.

While it plies in an overly-familiar documentary register, Sam Pollard's Two Trains Runnin', playing Friday, October 21 at 8:00 p.m. and Saturday, October 22 at 11:45 a.m., is nonetheless a rousing, revelatory film about the "two trains" of the early 60s, the music and the movement--that is, the blues and Civil Rights. Running on not-quite parallel tracks, they converged in the heady summer of '64. Unbeknownst to each other, two groups of white kids who loved 30s country blues headed South on quixotic quests to find their heroes (Son House on the one hand, Skip James on the other). They ran smack into Freedom Summer, which, as this living history lesson reminds us, was the campaign in which white college students from California and New York were to spend the summer in Mississippi campaigning for voting rights for African-Americans, among other things. Not surprisingly, the Klan and the cops did not distinguish between the blues fans and the Civil Rights kids. In a head-smacking coincidence, Freedom Summer campaigners James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwermer disappeared on June 21, 1964, the very same day Son House and Skip James were found. Now recognized as immortal giants, these men were plucked from obscurity late in life by these young white fans and placed before the spotlight of the Newport Folk Festival of '64. Those "nerdy" blues lovers, now seniors, tell memorable stories about the dangers and pleasures of those days. I won't forget the story about the "blues house," where all the "rediscovered" blues legends playing Newport that summer stayed--a kind of blues heaven where you could go from room to room and hear a different hero playing in each. This timely film reminds us that there are forces at work even now fighting to roll back the gains in society that, in the summer of '64, brave young people died for.

Thunder Road is a funny, unsettling short about the pain of mourning, playing in the Shorts 4: They Can't Go Home Again program on Saturday, October 22 at 7:00 p.m. It is a 12-minute, one-shot, essentially one-man film, featuring a remarkable tragicomic performance by the director, Jim Cummings, playing a heartbroken, damaged cop who sings Bruce Springsteen's immortal Thunder Road at his mother's funeral. It was her favorite song. He put me in mind of the kind of essentially good-hearted losers Ricky Gervais plays so well. You might think it sounds like a tearjerker, and I admit it got a bit dusty as I watched. But the film keeps you off-balance: you never know quite whether to laugh or cry. The young man's rambling remarks as he tries to reckon with his mother's short life are digressive but guileless, and somehow everything he's trying to say about her can be summed up in her love for Springsteen. His furious rendition of the song, at once gutsy and increasingly grotesque, features some very funny dance moves. Simultaneously a work of cringe-comedy and a portrait of anguish, the film is a concise character study, as well. So much flits across Cummings' mortified visage: grief, nerve, regret, triumph, shame, defiance.

Not to be missed is Gianfranco Rosi's unique documentary Fire at Sea, playing Saturday, October 22 at 7:30 p.m. and Tuesday, October 25 at 6:15 p.m., a great work of humanism and a storehouse of powerful imagery. (It won the top prize at the Berlin Film Festival, and it's the Italian submission for the foreign-language Academy Award.) The setting is Lampedusa, an ancient, tiny Italian fishing island, which for years has been the gateway to Europe for hundreds of thousands of migrants from Nigeria, the Ivory Coast, Syria, and points beyond. There is no narration or editorializing, but the situation is ripped straight from the headlines: souls crossing the sea on small, rickety, overstuffed boats, looking for freedom, knowing they'll die if they stay at home. Some 15,000 have died trying to make it. We follow the Coast Guard on rescue ops. They drag the sickest migrants off the boat, more dead than alive. Then, there is horrifying footage from the hold underneath: cadavers strewn with trash. Rosi secures rare footage from inside the immigrant holding center. At night, these largely North African men, who often turn up on the island burned with diesel fuel, look like gilded silhouettes in their gold-foil reflector ponchos. We meet a haunted, compassionate doctor tasked with examining the migrants after their sea voyage. Often, he must handle dead children. ("It is the duty of every human being," he says, "to help these people.") We also follow a young island boy with a lazy eye and no particular aptitude for being a sailor, the historic role for every Lampedusa boy. He might as well be on a different planet than the migrants. For great stretches there is no dialogue or music, and all of our information comes from Rosi's poetic visuals. I think of the deep quiet at the bottom of the sea as we follow a deep-sea fisherman, or the still of the early morning as a rescue chopper is wheeled out on the Coast Guard carrier's hangar. We occasionally visit the studio of the island's DJ, then cut to the boy's grandparents as they happily listen to the radio, the grandma serving the grandpa tea. As I watched the old lady make her bed, I mused over an old photograph on her nightstand. Suddenly, she picked it up, kissed it and spoke to it. It's a small moment, but it's indicative of this film's great, quiet heart.

Chan Wook-Park's exuberantly naughty, heavy-breathing (dare I say feminist?) The Handmaiden, playing on Sunday, October 23 at 8:15 p.m. and Tuesday, October 25 at 8:30 p.m., makes your pulse race. It's an erotic revenge-drama/period romance. [It would be easy to spoil this picture, so I've tried not to spill too much here. By rumor and reputation, you may already know about the theme of giddy sexual discovery.] Three devious characters swindle each other in a sumptuous mansion in Japanese-occupied Korea. Kim Tae-ri poses as a Korean handmaiden to the Japanese Lady Hideko, played by Min-hee Kim. Actually, the handmaiden is part of a plot to get her hands on the lady's "assests." Min-hee Kim played such an everyday woman in Hong Sang-Soo's Right Now, Wrong Then; it's a treat to see her play Lady Hideko, who's about as far from that as can be. There's always a secret flitting about those eyes, that smile. Jung-woo Ha is a suave professional con man posing as a Count; also in pursuit of the fortune, he believes himself to be playing the ladies off against each other. The movie's got double-crosses, triple-crosses and a perverse uncle. In the sanctum of his cherished library of rare dirty books, this debauchee makes his niece--Lady Hideko--read scandalous stories and perform certain feats for audiences of sado-masochistic men. It's more Fanny Hill or The Pearl than it is Salo. From Chan Wook-Park we expect, and get, gorgeous cinema. Told in three parts, the intricate narrative is a marvel of construction. After extended coyness, exquisitely tense, it builds to quite a release of grinding, explicit lovin', but these scenes somehow feel celebratory rather than exploitative. The rest of the world drops away. I won't forget those jingle bells on a rope! The Handmaiden's wicked spirit is infectious.

I thought very highly of André Téchiné's Being 17, which plays Sunday, October 23 at 3:15 p.m. and Monday, October 24 at 8:30 p.m. Finally, the single best film I saw in the course of my festival survey was Barry Jenkins' Moonlight. It plays Wednesday, October 26 at 7:30 p.m. I wrote about them both for CINE-FILE Chicago, and you may read my capsule reviews here.

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Thursday, October 13, 2016 at 06:31PM

Thursday, October 13, 2016 at 06:31PM

I had a chance to check out a handful of the myriad exciting films on offer at the first week of the 52nd Chicago International Film Festival. I'd point you toward the following.

I heartily recommend Bertrand Tavernier's documentary Journey Through French Cinema, playing on Saturday, October 15. I wrote a blurb about it for CINE-FILE Chicago. To check out my capsule review, click here and scroll down.

From Iran comes a film that wins my seal of approval, Adel Yaraghi's well-turned drama Finals, co-written with his mentor, the late master Abbas Kiarostami. It tells the tale of a bitter adolescent and his mother's attempts, along with her fiancé (the boy's teacher), to cajole him into sitting for his final exam. It's also about the boy's friendship with an alienated friend whom the adults regard as leading him down the path to juvenile delinquency. As observant as a good short story, it conveys a real feel for Tehran life. It plays Saturday, October 15 at 6:15 p.m., Sunday, October 16 at 2:30 p.m., and Wednesday, October 19 at 12:30 p.m.

In Terrence Davies' soulful, unsentimentally beautiful A Quiet Passion, playing at 5:30 p.m. on Sunday, October 16, Cynthia Nixon is the fiercely agnostic, independent Emily Dickinson, ensconsed in her famous second-story bedroom. This very funny film boasts such comic brio in its banter, such charged quiet in its candelit interiors, where worlds of inner emotion swim. The ticking of a clock tolls those looming universals: time and mortality. In the poet Dickinson, the poet Davies meets a subject where his form finds its ideal content. Not to be missed.

Not to be missed is Steve James' documentary ABACUS: Small Enough to Jail, playing on Tuesday, October 18 at 6:00 p.m. I wrote a blurb recommending it for CINE-FILE Chicago. To check out my capsule review, click here and scroll down.

Alain Guiraudie's droll, startling Staying Vertical, playing at 8:45 p.m. on Wednesday, October 19, is a frank, comic picaresque about a feckless screenwriter wandering the French countryside, looking for inspiration for his next picture. He seems to take life as it comes, and soon enough he finds himself cradling a newborn across city and countryside, committed to protecting his baby as wild wolves abound. The sexual border between gay and straight is highly porous here, and so is reality, which blends into metaphor quite exhilaratingly. For tastes that run to the shocking and original, this is essential viewing.

One of the highlights of my fest sampling so far is Juho Kuosmanen's very original boxing movie/love story The Happiest Day in the Life of Olli Mäki playing on Wednesday the 19th at 5:45 p.m. and Thursday the 20th at 8:30 p.m. To check out my capsule review for CINE-FILE Chicago, click here and scroll down.

Paul Verhoeven's controversial, perversely entertaining Elle, plays at 8:30 p.m. on Thursday, October 20. It's a darkly satiric drama/thriller about sex, power dynamics and sadomasochism, with a sly performance by the great Isabelle Huppert as a truly odd duck, a boss whose company makes video games involving loosely-veiled rape fantasies. The movie turns on her own assault and rape, an incident she regards strangely ambiguously, turning it over with clinical detachment. We seem to be at a point where just about everybody agrees Verhoeven's a subversive genius. I'm still mixed on him, but there's no doubt this is one helluva movie.