"Even if nothing turned out how we'd hoped, it would not have changed what we'd hoped for."—Peter Weiss via Jean-Luc Godard, or vice versa

"Maybe The Image Book is his love letter to cinema. He is reflecting on his whole life."—Fabrice Aragno

In my (image) book, a new effort from Jean-Luc Godard, one of the medium's pioneers and a huge influence in my life, is always an event. The Image Book is complex and iconoclastic and homemade (handmade, actually, hence the leitmotif of hands). It's highly personal and often ravishingly beautiful, very much in the contemplative mode of Late Godard. It's a bravura display of the unique approaches to montage ("thinking with one's hands") and mise-en-scene that he's been developing his whole career. In tone, it's alternately elegiac and angry, alienated and engaged, lulling and abrasive. It's not likely to win over folks not already seduced by Late Godard, but then they haven't been on board for the last, oh, 52 years, ever since his New Wave period ended with Weekend. As for me, The Image Book awakened all my senses. I came out feeling more alive, newly attuned to my mind's eye's perspective and point of view.

The new film is one of his magpie-art catalogue-essays, in what might seem like the familiar mode of Histoire(s) du Cinema (1988-1998). Godard builds collages from characters and fragments of Western culture down the centuries, which appear almost as if filtered through a dreaming mind's unconscious, an effect a bit akin to Dylan's "Desolation Row." Thus, Godard brings into play ideas about, say, the relationship between literature and cinema.

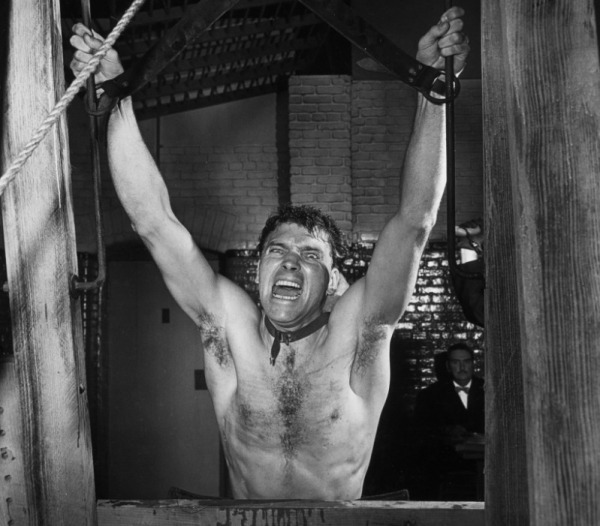

Typically, his collage films are critiques of the 20th century, of history as a nightmare from which we are trying to awake, in one of Joyce's snappier lines. This is conveyed here by everything from clips from Pasolini's Salo: 120 Days Of Sodom, quoted often, to shots from Paisan (by his hero, Roberto Rossellini), to ISIS videos.

Godard, then, is perhaps the T.S. Eliot of film—poetic, densely allusional—or its James Joyce—associational, punning, digressive. Or maybe he's its Thelonius Monk, who daringly rethought harmony, rhythm, etc., or the great hip-hip DJ of film. Or he's Brecht, obsessed with making us see the familiar in a new way.

In any case, I think it's fair to say modern cinema begins with him.

Reading up on the film before and after seeing it, we learn that

The Image Book is in five chapters, like the fingers of a hand, or maybe there's six parts (the five "fingers" as a long introduction, and the "hand" that includes them all). I'd enjoy seeing the film again to see if it really adheres to this scheme. In Dmitry Golotyuk and Antonina Derzhitskaya's

illuminating interview with Godard, he breaks the chapters down like this:

1. The first finger is remakes: that is, copies.

2. The second finger is war, triggered by Soirées de Saint-Pétersbourg (Joseph de Maistre, 1821).

3. The third is travel, inspired by a verse by Rilke ("those flowers between the rails, in the confused wind of travels"), as well as Baudelaire ("Show us, as if stretched across canvas, your recollection in their horizons' frames.") A theme here is trains: Godard juxtaposes trains as a metaphor for the cinematic joyride with trains used in history as conveyance to the death camps. (It's extraordinary how he conveys all this in just an instant, in just a spine-tingling bit of montage involving fresh hyper-saturated footage of a toddler excitedly waiting for a train to come in, on what could even be an El platform).

4. The fourth finger is law, inspired by Montesquieu's book, The Spirit of the Laws (1748).

5. The fifth is "La région centrale," inspired by Michael Snow's famous experimental film of the same name. Godard explains that, in his film, the "central region" is the love between a man and a woman, which is taken from Dovzhenko's

Earth. An emergent theme of this finger is Arabia. It is concerned with how concepts of Africa and the Middle East are produced. For the first time, as

Daniel Morgan has noted, Godard surveys Arab cinema, fighting the image of Islam in the West (those ISIS videos) with images from Arab cinema itself. This section includes footage shot by Godard and his cinematographer, co-editor and co-producer, Fabrice Aragno, in La Marsa, Tunisia. Godard's long been a partisan of the Palestinian cause:

Jusqu'à la victoire, an explicitly pro-Palestinian film embarked on in 1970 during his Dziga-Vertov period, was never completed. Still, with

The Image Book, he's now listenting to Arabia speaking for itself.

Aragno

told Amy Taubin, "Jean-Luc does the edit on videotape and then I redo everything on computers." Essentially, Godard uses a "primitive" analog recorder to tape things he plays on TV. Then, Aragno transforms the tape into digital cinema, while heeding Godard's directive to keep a palimpsest of the analog textures. "The painter keeping the evidence of the brush stroke," as he puts it.

I learned a lot about their process from reading the insightful articles by Taubin and Morgan in Film Comment. As Taubin notes, in his collage films Godard creates a mix-tape out of history as written onto an old-school medium ("film," understood as an experience that is, by definition, a work projected onto a screen in front of an audience), and then re-writes that history onto a new medium, in this case digital, which has a private, personal capacity, almost a one-to-one mode of communicating, and one over which we have more control.

It's also fun to learn how they did a neat effect where they "pop" a film clip's aspect ratio. Aragno: "This happens when he records from his TV onto his old DVCAM analog machine...The TV takes time to recognize and adjust to the format of the DVD or the Blu-ray."

In The Image Book Godard deploys some of his usual strategies for keeping passivity at bay in his viewers. He's still challenging us, for one, to learn to listen. Occasional black frames, such as the ones inserted into that famous "Tell me you've always loved me" back-and-forth between Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden from Johnny Guitar, are an homage to the primacy of sound in movies, of the kind that critic James Monaco has long analyzed in his work. There's the signature layered language becoming a babble (or babbling brook), the jagged blasts of music that abruptly cut out.

The personal is in there, as well, in the form of the many nods to the presence and work of Anne-Marie Miéville, his longtime partner, as well as to the many fragments of his own work.

I was lucky enough to see

The Image Book at the Gene Siskel Film Center, which went to the trouble of installing a 7.1 stereo surround-system just for this movie.

Get your tickets here. Godard has created a soundscape as three-dimensional as his images for

Goodbye to Language. His rough, raspy voice, itself a marker of the passage of time, surrounds you. At one point, the voices merge and crescendo, becoming increasingly urgent. At another, as a procession marches into a ballroom, the sound begins in a corner to your left, moves behind the screen, moves over to your right, and then circles around behind you.

He wants to convey something urgent, here, as if the film is a summation of his career-long attempt to figure out how best to use film to speak directly to the audience. The thing is, his need to communicate is always conflated by an almost equally powerful urge to be inscrutable, to hide meaning, to be cryptic, to make a puzzle we have to solve. I confess that there's something about this that appeals to me, temperamentally. I happen to like puzzles.

What's more, his work's never been afraid to be about confusion. He's always been honest about the fact that his films are about feeling their way towards something, about working it out onscreen. As he wrote in Godard on Godard about Two or Three Things I Know About Her, "I hope [the film comes off]; if not all the time, at least in certain images and sounds." I do love that approach.

As Monaco has pointed out, his work's also always been about language, not only his powerfully lucid understanding of "the complex language of film and TV," but also the way that "language, inherently ambiguous, serves as a barrier to communication and precludes love. Even body language fails."

In the end, I'd be bluffing if I pretended truly to understand Godard, or even to be deeply grounded in the works he quotes, though I've delved. (And who can say how deeply grounded he is in them, himself? Likely, he takes what he can use and disregards the rest, a wise move). I have dipped into Edward Said's Orientalism, a classic work on, in a sense, images and power ("puissance," in French), and kept thinking of it during the Arabian sections.

He will perhaps always be an emblem of the '60s—he was never quite as in touch with the zeitgeist again. Still, I wasn't even born then and I know his work speaks to me, in the sense that his films play me as much as I play them. In truth, he's spoken to us in every decade, and here he is in 2019, speaking to us urgently again. At 88, he's still experimenting, still playing with the form.

What is he saying with The Image Book? I believe he's almost pleading with us: look, it's not too late. We can still change things, but we've got to listen. We've got to hear other voices, imagine other futures. It's up to us. After all these years, Godard is still about using film as a way to grapple towards a better future. I find that inspiring.

Plus, he loves dogs. Remember Roxy?

"Godard is a filmmaker who found himself, by chance perhaps, at the precise center of the intellectual web of the 20th Century. If we have to leave one filmmaker's collected works behind us for the Eloi to discover 800,000 years from now, let it be Godard. It's all here: the European and the American, the modern and the postmodern, the politics and the poetry, the genres and the dialectic, the literary and the cinematic, the images and the sounds, the color and the black and white, the montage, the mise-en-scene, the thoughts and the feelings. You get the idea. This is not to say that Godard made great movies. There's nothing like Citizen Kane or even 2001 among them. But he did make remarkably rich and resonant movies. Like a ballroom globe, he reflects all the colors of our film culture." —James Monaco

Rating: ****1/2

Key to ratings:

***** (essential viewing)

**** (excellent)

*** (worth a look)

** (forgettable)

* (rubbish!!)

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Friday, February 22, 2019 at 03:03PM

Friday, February 22, 2019 at 03:03PM