THE BEGUILED

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Wednesday, June 28, 2017 at 04:07PM

Wednesday, June 28, 2017 at 04:07PM  Sofia Coppola's remake of THE BEGUILED is a slyly subversive, often quite funny, reinterpretation of the pulpy, febrile Don Siegel/Clint Eastwood film of 1971. For better and for worse, it's not the gamey kind of fun that movie was. Spooky and rather arty itself, the Siegel was either a twisted feminist or a misogynist classic, depending upon your point of view—a (quite revealing) male anxiety dream about women's lib. (It could also be read as a Vietnam allegory). It was an eerie folk ballad, a cautionary tale wherein the Big Bad Wolf falls into a coven of witches.

Sofia Coppola's remake of THE BEGUILED is a slyly subversive, often quite funny, reinterpretation of the pulpy, febrile Don Siegel/Clint Eastwood film of 1971. For better and for worse, it's not the gamey kind of fun that movie was. Spooky and rather arty itself, the Siegel was either a twisted feminist or a misogynist classic, depending upon your point of view—a (quite revealing) male anxiety dream about women's lib. (It could also be read as a Vietnam allegory). It was an eerie folk ballad, a cautionary tale wherein the Big Bad Wolf falls into a coven of witches.

Both movies adapt a Thomas P. Cullinan novel of 1966, which I haven't read. The setup: a dissembling, charming Union soldier with a wounded leg, McBurney (Colin Farrell, stepping into the Eastwood role, now more object than subject of the story), finds shelter at a southern girls' school housed in a plantation, where he's viewed with a mix of fear and fascination by the women. They take turns waiting on him and competing for his affection. What at first seems a male-supremacist dream turns into a nightmare.

As writer and director of this remake, Coppola had the interesting idea to make a critique, telling Siegel's woman-spooked fable from the corseted females' perspective. However, you wouldn't know that if you haven't seen the Siegel before going in, as I had not. (I've since caught up.) You'd simply enjoy the new movie for its absorbing narrative, and for the sly interplay of the fine actresses, Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst, and Elle Fanning, bound in tangled lines of allegiance and suspicion, as conveyed through glances and witty editing. It's an exquisitely modulated work of art.

As writer and director of this remake, Coppola had the interesting idea to make a critique, telling Siegel's woman-spooked fable from the corseted females' perspective. However, you wouldn't know that if you haven't seen the Siegel before going in, as I had not. (I've since caught up.) You'd simply enjoy the new movie for its absorbing narrative, and for the sly interplay of the fine actresses, Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst, and Elle Fanning, bound in tangled lines of allegiance and suspicion, as conveyed through glances and witty editing. It's an exquisitely modulated work of art.

This being Coppola, this movie's atmospherics are, of course, savory. (She won the Best Director prize at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival for this film, marking the first time in 50 years a woman has won the award, and only the second time ever.) Shot in a New Orleans mansion on 35mm, it's an achievement in candlelit moviemaking, by Coppola and cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd, that can be mentioned in the same sentence as BARRY LYNDON. If anything, the movie thickens the Southern Gothic air. I think of a gorgeous moment when the sun breaks through the mist-enshrouded, Spanish moss-draped oak trees. The grounds teem with cicadas, chirping wall-to-wall on the soundtrack. I thought I'd be hearing them in my dreams. Just about every shot is a feast for the eye, as when she arranges the woman around the piano, a portrait in pastel dresses.

It's more subtle and nuanced than the 1971 film (it couldn't be less), a comedy of Victorian manners, when bared shoulders were risqué. Some will find it too muted. There's none of the feverish inner thoughts of sex-starved women—in the original, these just about scream "wishful male projection." Ms. Martha, in the Siegel: "If this war goes on, I'll forget I'm a woman." There's no fantasy threesome resolving itself into a pietà, dreamed up by Ms. Martha. Also gone is the lurid incest storyline.

(Coppola's version cuts the character of the slave woman, as well, a decision that has already kicked up much discussion. In her version, the slaves have run off. Not having seen the original when I went in, Coppola's story, for me, was about these women left completely to fend for themselves).

Her version is a lot of fun in its own right, much of it based on table-turning. (She's said in interviews she was keen to objectify Farrell for the benefit of the gay male, and female, gaze). When Kidman says to her young Southern charges, attempting to impart a lesson, "The enemy as an individual is not what we believe," she's really talking about men and the war that is the true subject of both films—not the Civil, but the one between the sexes. To humanize the "enemy," i.e., women in the original, is part of the point of this new version.

As Ms. Martha, the po-faced, refined headmistress, Kidman dials down the deliciously campy menace of Geraldine Page. Through male eyes, Ms. Martha was an evil castrater: through Coppola's, she's just doing what needs to be done. Beneath her breeding, Kidman reveals a merciless core, embodied in a late gaze down the table into the camera that, for timing and comedy, must rank as one of the most delightful shots in modern filmmaking. A faraway-eyed Kirsten Dunst plays the virginal teacher, Edwina. As originally portrayed by Elizabeth Hartman, she was pretty much the only good human in that film. Like McBurney, she feels like a prisoner—"a sleeping beauty needing a man's kiss to awaken her," per Clint in the original. Dunst and Coppola feel Edwina's straitened life more acutely, fleshing out the dimensions of her longing, her ache for experience. Elle Fanning plays the horny adolescent who chafes at the rules, rather a poxy young doxy in the original. In Coppola and Fanning's nonjudgmental take, the character is a searching teenager, and the movie shifts some of the onus onto McBurney for exploiting her.

Sofia Copolla's shift of empathy in her version of THE BEGUILED reverberates beyond the edges of this remake. It makes you think about how the rest of film history would be different, from a female point of view.

Sofia Coppola's THE BEGUILED (2017, 94 min, DCP Digital) plays Landmark’s Century Centre Cinema starting June 29. Check Venue website for showtimes.

Rating: ****

Key to ratings:

***** (essential viewing)

**** (excellent)

*** (worth a look)

** (forgettable)

* (rubbish!!)

BEAT THE DEVIL, Redux

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Wednesday, June 28, 2017 at 09:01AM

Wednesday, June 28, 2017 at 09:01AM  "In the South of France, anything is possible!" Andre Bazin once declared. That is the setting for the 1951 novel Beat the Devil, and though John Huston's one-of-a-kind, endlessly funny film version moves the action to Italy’s Amalfi coast, it preserves the anything-goes spirit. Now, "the longest running cult favorite in history," as James Monaco called it, is back, thanks to a new 4K restoration, in all its strange, uneven glory. Even today, people exist who can recite swaths of its dialogue as if it's verse.

"In the South of France, anything is possible!" Andre Bazin once declared. That is the setting for the 1951 novel Beat the Devil, and though John Huston's one-of-a-kind, endlessly funny film version moves the action to Italy’s Amalfi coast, it preserves the anything-goes spirit. Now, "the longest running cult favorite in history," as James Monaco called it, is back, thanks to a new 4K restoration, in all its strange, uneven glory. Even today, people exist who can recite swaths of its dialogue as if it's verse.

Humphrey Bogart plays a middle-aged roustabout who, according to the novel, once rather had the reputation of a "second Lawrence." Those were the "good old" prewar days; now, the social order is upended, the Atomic Age looms, and he is reduced to being a hired agent of "the committee"—a a comic little crew, as would-be international men of intrigue go. As Roger Ebert notes in his Great Movies essay on the film, we smile simply upon sight of the great character actors comprising this seedy gang, staking everything they've got on a plot to make a fortune in the illegal postwar uranium rush in British East Africa: Peter Lorre, Robert Morley, Ivor Barnard, and Marco Tulli.

There are other stranded Africa-bound travelers. Jennifer Jones, hair dyed blonde, plays a woman who, shall we say, "uses her imagination rather than her memory." (She tells lies that are "truer than true," as she puts it). That is, she's a blithe fabricator—right up until the great moment when she finally, deliciously, tells the truth. She's married to the silly Edward Underdown, a stiff-upper-lipped Englishman whose confidence about the way the world works marks him as a man of the old world—and something of a fool in the new one.

Underdown is much admired by Bogart's wife, the wonderful Gina Lollobrigida, playing an Anglophile. ("Emotionally, I am English," proclaims the uber-Italian actress). Jones, in turn, carries a torch for Bogie. The restoration removes some censorship, but even so, the movie is not nearly as pungent about this double infidelity as the novel. That is to say, with the exception of a restored, and scandalous, shot featuring Lollobrigida's cleavage. (The old version faded out before her bust could fill the screen.)

The novel was the creation of Claud Cockburn, the great Scottish/Irish journalist and communist. (The credited "James Helvick" was a Cold War sobriquet: the novel and film appeared at the height of the blacklist and McCarthyism.) Every week in the '90s I would eagerly pour over Claud's son Alexander's mighty two-page column in The Nation, "Beat the Devil," named in homage. Huston, a friend of Cockburn's, was keen to turn the novel into a film, yet he turned up in Ravello, where cast and crew had convened, with more enthusiasm than script. (Treatments by Cockburn himself, as well as by Anthony Veiller and Peter Viertel, hadn't work out.) David O. Selznick, Jennifer Jones's husband, thought to bring in the hot and controversial young writer Truman Capote. (In the Chicago Tribune, Michael Phillips noted the sly joke that Lorre's hair is dyed to look like Capote's.)

Capote's great innovation was to turn the material into a campy parody, making the picture a sendup of '40s adventure movies. Pauline Kael, a big BEAT THE DEVIL fan, went so far as to say it "finished off" the form, much as THE LONG GOODBYE later would the private eye genre. Actually, I think Capote could've taken it even further in the direction of parody—cf. S.J. Perelman spoofing Raymond Chandler. And didn't the '40s pictures themselves sometimes have a knowing wink? A few scenes feel like they're not sure if they're straight; as Kael noted, Bogie doesn't seem always to be in on the lampoon.

As the set became a party, Capote legendarily made up the screenplay as he went along, beating a daily deadline, with Huston handing out the pages to the cast right before filming. Upon examination, however, much of the funniest dialogue is right there in the Cockburn novel, including Lorre's line that many Germans in Chile have become called "O'Hara," as well as Lollobrigida's quoting of the novelist George Moore, cited approvingly by Ebert. ("I believe," he writes, that Moore "has not been quoted before or since in any movie.") On the other hand, some of the most-loved lines seem to be Capote's, including Lorre's famous "time" speech. On the other, other hand, Lorre and Morley sometimes made up their own dialogue on the spot. Whatever its tangled provenance, it must be said that the "screenplay," as it plays on screen, is a witty and cagey adaptation, sparkling with "bon mots."

For the first time in decades, the visuals sparkle as well, thanks to the new 4K restoration overseen by The Film Foundation and Sony Pictures's Grover Crisp. Its limpidity will shock you if your previous viewings, like mine, were on scratchy VHS. The restorers went back to the original 35mm negative. (Asking if we couldn't have a nice 35mm print alongside the DCP as part of the restoration feels almost churlish, or like one of those existential questions). Freshly scrubbed, Oswald Morris's gorgeous black and white cinematography gleams with granular detail and texture, as well as an almost 3D sense of depth. A shot framing Bogart and Jones canoodling high above the Tyrrhenian Sea is breathtaking, almost vertiginous: when the camera pulled back and up, I felt I might fall right through the frame. In my notes I have, "the view is stunning"; later, when I looked up what Farran Smith Nehme wrote at Film Comment, I was pleased to see she felt the same.

The restoration removes Bogart's narration, and thusly the movie's flashback structure. It runs roughly five minutes longer now. Much of the added material restores Jones and Underdown's stroll from near the beginning of the novel; fans of the book will be glad to have restored to celluloid Jones discussing her Spanish nurse, and why it's important to spit first. A Rita Hayworth pinup in the office of the "Arab inquisitor" (Manuel Serano, with hookah, naturally), previously obscured by a shadow, can now be seen in all its glory. The laughs everyone had making BEAT THE DEVIL are contagious: after 64 years, it's still a hoot. By the end of this freshly showered version, my face ached from smiling.

John Huston's BEAT THE DEVIL (1953, 95 min, DCP Digital) plays at the Gene Siskel Film Center from June 30 through July 5. Check Venue website for showtimes.

BAND AID (on CINE-FILE Chicago)

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Saturday, June 17, 2017 at 01:58PM

Saturday, June 17, 2017 at 01:58PM I was mixed, leaning affectionate, on Zoe Lister Jones's BAND AID. It's worth a look. To read my review at CINE-FILE Chicago, please head here and scroll down to the "Also Recommended" section.

RAISING BERTIE

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Wednesday, June 14, 2017 at 08:27AM

Wednesday, June 14, 2017 at 08:27AM

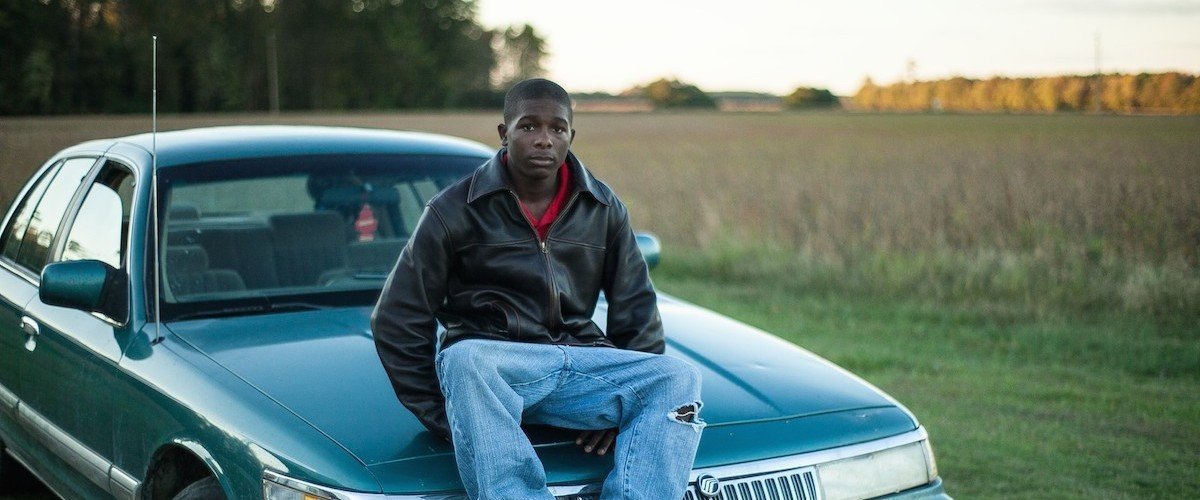

Margaret Byrne's empathetic, thought-provoking RAISING BERTIE begins with a rushing road. A teenager, Reginald ("Junior"), comes bicycling towards us. The film introduces us to him and two other young African-American males living in Bertie County, North Carolina, and over the next hour and a half we get to know them. To make this film, Byrne ensconced herself in the community for six years, reminding me of the way Barbara Kopple settled into HARLAN COUNTY, U.S.A. We watch these boys grow into men, sharing in their hopes, dreams and struggles. Thus, RAISING BERTIE deserves a place beside the great achievements in longitudinal film, from Michael Apted's UP series to Richard Linklater's BOYHOOD to Steve James's HOOP DREAMS. It upholds the worthy tradition of social-issues filmmaking as practiced by Frederick Wiseman, Albert and David Maysles, Gordon Quinn, and Chicago's own Kartemquin Films, which produced. It's also fair to say that it makes us think anew about some of the problems inherent to cinéma vérité.

We hear a lot about at-risk urban youth, less of their rural counterparts. Rarer still is an approach that values what these young men feel—in a word, that treats these lives as if they matter. After all, our culture teaches young men to keep it all in. While the cliché is that these men are not "articulate," in fact there is a music to their language. The film often subtitles their speech, for the benefit of we outsiders who don't have an ear for it.

Junior has a great smile that, in a flash, can turn into a grimace. David (“Bud”) is a generally good-natured young man with a volatile temper. He works with his dad, who runs a landscaping business tending to the big houses on the wealthier side of town, and he also drives a tractor in the cotton fields. Davonte (“DaDa,” pronounced with long A's) is a quiet fellow who wants be a barber.

At the outset, Junior says something that gives us an idea of how innocent he is —how he's just a kid—but also of of the adult, ugly realities he faces. He says that when he grows up he wants to be rich, so he thought about selling drugs. However, he never really wanted to; plus, his mother says she'll whup him. So maybe he'll just be a "secret agent." (Or, failing that, a mechanic.) He likes living in Bertie and "smelling the corn."

Bertie's population is 80% black. There's not a lot to do for work or recreation. There are, however, a lot of opportunities to get into trouble. As a title advises, there are 27 prisons within a 100-mile radius of Bertie County. In fact, DaDa's brother, who boasts the memorable sobriquet "Mickey Mouse," is locked up. His brother is, DaDa admits, something of a kingpin among local drug dealers. DaDa and his mom, Esther, care for Mickey Mouse's baby while he's in jail.

DaDa, Bud and Junior attend an alternative high school called the Hive, expressly set up to meet the needs of black boys. Vivian Saunders, the kindly executive director, wants to pull suspended boys off the streets and back into the school system, while giving them the "love and caring" they don't get there. "I tell them they can be educated at the Hive or be educated in jail," says Saunders. While DaDa is bright—he has a nice ironic sense of humor—he's always required extra time for his schoolwork. The Hive makes him feel like he can learn. When the school board shuts the Hive down, the boys awkwardly integrate into the official Bertie High. Saunders worries, have we given them the tools to survive without getting in trouble? She offers an interesting analysis of the role of violence in these young men's lives: "It goes back to being a tenant farmer," she says. "They have to prove themselves through violence and joining gangs."

The violence seems to spring, as well, from a fierce disinclination to be looked down upon—to be "disrespected."

Violence can be passed down. Junior's mom Cheryl is a survivor of domestic violence at the hands of Junior's dad, who went on to murder a subsequent girlfriend (and a deputy). One of the movie's most heartbreaking scene is the one where Junior visits him in prison. Even Bud's dad, the hardworking landscape architect, beat him until he "peed himself," according to Bud, as a method of discipline.

Seen in the background in a shot at Bertie High School is a banner reading, "Children learn what they live."

Cheryl, Junior's mom, works three jobs, yet she still eventually loses the house. Esther, Dada's mom, is estranged from his dad, Ernest, who comes off as a rather self-centered man with a drinking problem. Movingly, DaDa still yearns for his approval and attention. Veronica, Bud's mom, is a cherubic, religious woman who works at the chicken processing plant.

RAISING BERTIE begins its run on June 16 at Black World Cinema at the Studio Movie Grill Chatham (210 87th St.) – Check the venue website for showtimes. The filmmakers will be in person at the weekend screenings.