Jazz, Blues and Beyond: A Chicago Music Tour

Sunday, June 23, 2013 at 02:17PM

Sunday, June 23, 2013 at 02:17PM On a recent Saturday morning Karolyn and I hopped aboard the Chicago Detours “Jazz, Blues & Beyond Bus Tour,” a birthday present from her to me. I’ve found on my trips to Europe that walking in the footsteps of the artists somehow enhances how you experience the art. Wandering through the pubs and lanes of London where Shakespeare trod, say, you get a sense of his stomping grounds, of space and distances. What was abstract becomes physical. So to do this in my own town, Chicago, with, say, Muddy Waters instead of Bill Shakespeare, was a kick.

We’d gathered on a Saturday morning at the great downtown record shop, the Jazz Record Mart. As we pulled away from the curb our tour guide, Amanda Scotese, posited Chicago as a place of (productive) tension, a place where people came together (and not) over music. In that sense, an alternate title for her tour could have been the “Jazz versus Blues tour.” She set up a dialectic that was really just a fun framework for thinking about jazz and blues in terms of oppositions: north versus south, head versus heart, mood versus story, etc.

Our bus featured video screens like on an airplane, so she could play us footage of the jazz and blues musicians she was setting in opposition. What contrasts could we hear in, say, Mahalia Jackson versus Scott Joplin, spirituals versus ragtime? People volunteered some good stuff: soulful versus jaunty, rural versus urban, on the beat versus syncopated. She gave us Charlie Parker versus Muddy Waters, leading to Tortoise and the White Stripes, respectively.

All the while we were shooting up north, bound for Uptown, a neighborhood I pass through twice a day on the “El”. On our way Amanda pointed out the building on Argyle that once housed Essanay Studios, where Charlie Chaplin made films.

As we headed Uptown, Amanda explained that Chicago kept expanding: you had to drive or take the streetcar to get to Uptown. It was the “end of the line.” The Green Mill, which once took up a whole Uptown block, was a roadhouse; “roadhouse” meant you had to drive to get there.

She showed us a great clip of Gene Krupa with trumpeter Roy Eldridge and singer Anita O’Day doing “Let Me Off Uptown,” a very early integrated duet (circa 1941), playful with sexual innuendo.

As an aside, we learned that “juke joints” were places that had jukeboxes, and jukeboxes played videos like this one.

We alighted the bus and stood studying the Aragon. I admire it from my levitating El car every day (and in fact I saw one of Nirvana’s last-ever shows there almost 20 years ago). Now we gave it a Rick Steves-like going over, admiring its Spanish façade with its swirling columns, the faces peering out of its crisscrossing brickwork, its shields and scalloped shells. This was an exotic place for rural and working people who traveled great distances to come dancing in the big city. (Bands were told to play faster so boys and girls wouldn’t dance too close.)

We strolled over to the corner of Broadway, from which vantage point we had before us the Riviera, the Green Mill and the Uptown Theater. Amanda asked us to imagine the scene as it would have been at the height of the Jazz Age, say 1926: this was Chicago’s Times Square, a neighborhood of glittering ballrooms and movie palaces. It was the place to be. Squinting, you could almost see gangsters stepping out of gleaming cars.

We clambered back aboard the bus. It was time to head down to the South Side to Bronzeville, that historic African-American neighborhood.

As we rounded corners Amanda pointed to the site of Lincoln Gardens on 31st Street, one of the great “Black and Tan Clubs,” which welcomed blacks and whites to mingle, dance and hear music together. Joe "King" Oliver's Creole Jazz Band kept ‘em dancing here in the early 20’s. Those were the days when cats like Bix Biederbicke, a young white fella, would take the train to Chicago to sneak into speakeasies to hear some “hot jazz,” jamming with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings.

As an aside, I hadn’t realized how important New Orleans musicians were to jazz innovation in Chicago, all those greats like Mahalia Jackson coming up with the Great Migration.

We passed Olivet Baptist Church, the oldest African-American Baptist church in Chicago and itself a great catalyst of the Great Migration. Amanda called it a “key to the neighborhood.”

As the bus rumbled down State Street between 31st and 35th, Amanda pointed out that this particular strip was once known as “The Stroll,” the vice district. These were the days when jazz was associated with sleaze. Today “the Stroll” is the notably unsleazy campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology.

We came to a stop at an ACE Meyer Hardware Store. What!? you exclaim. Had this suddenly become “the Chicago Hardware Shop tour?” Allow me to explain. This hardware store was once the Sunset Café, a.k.a. the Grand Terrace Cafe, a very important "Black and Tan club” featuring Louis Armstrong’s big band (another son of New Orleans, of course). Cab Calloway and Earl "Fatha" Hines came up here under Armstrong before becoming the bandleaders themselves. In fact Hines would go on to lead the band there for twelve years. On the way there Amanda had shown us a photograph of the Earl Hines band during this residency, featuring a young Sun Ra, no less!

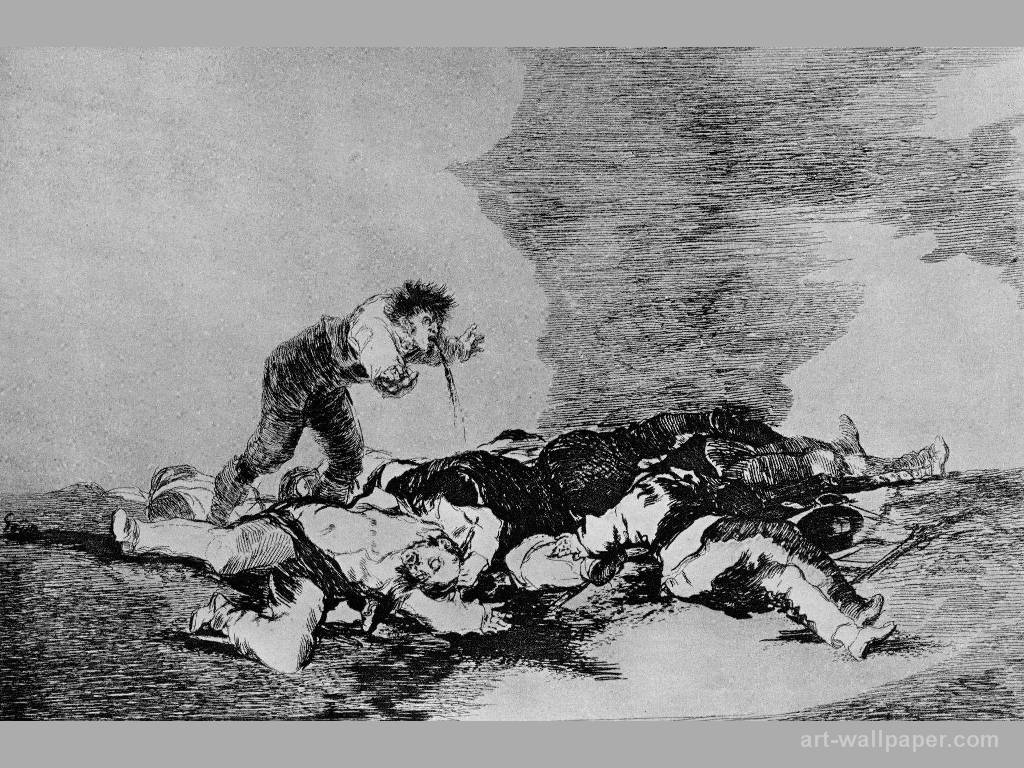

We went in and headed for the back. A few at a time we climbed a few wooden steps. We stepped into a narrow, cluttered office. Lo! We were onstage at the Sunset Café! The original murals are still there, visible around the duct and piles of boxes. A topless demon lady clawed the skin of a great drum. Climbing back down to the floor, we stood amidst aisles of hardware supplies imagining the floor filled with tables draped in elegant white tablecloth.

Back aboard the bus we passed Pilgrim Baptist Church, designed as a synagogue by no less than Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler, built in 1890-1891. It was the “heart of Bronzeville,” one of the birthplaces of gospel music in the 1930s. Thomas A. Dorsey, the "Father of Gospel Music", was its music director.

Next up for our merry bus: the “blues” part of the tour. That meant we had to talk about the Chicago Defender, the country’s most important black newspaper. It was the catalyst for the black exodus, the Great Migration, which hit its peak in the 40s and 50s. It wrote about Chicago as a place of hope for African-Americans, a place where housing and jobs could be had. “Blues is hopeful music,” as Studs Terkel put it from our screens. “I may be down now, but I won’t be down forever.”

We rumbled up South Michigan Avenue, up historic “Motor Row,” past the great display windows which once showed off their proud auto showrooms. We trundled up Record Row, grinding to a stop at 2120 S. Michigan, that address that rings out in music history. This was Chess Records (today renamed the Willie Dixon Blues Heaven Foundation). To some, this is the “birthplace of rock & roll,” Amanda told us, and quite right she was. Interesting to think about which has the stronger claim as birthplace of rock & roll, Chess or Sun Records in Memphis (which I've also visited). Hometown pride compels me to proclaim that Chess has as strong a claim as any.

We didn’t go in. Amanda offered that there’s nothing much to see inside, which is kinda true. Still, as someone who’s been inside twice, it’s still pretty cool to stand on the same floorboards as Muddy and Jimmy Rogers, Howlin’ Wolf, Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley.

We had to finish up by taking a trip to Maxwell Street, ground zero for the Chicago Blues, once a teeming, communal place where people gathered around music (not unlike Grant Park today, Amanda offered). Every musician had his or her corner, such as Blind Arvella Gray, who now appeared on our video screens. Like the Stroll, the old Maxwell Street Market flea market is gone today, of course. However, we stopped next to a statue commemorating the days when the blues rang out: a bluesman sitting on a box, with his harp by his side.

We had one more treat in store: a harp lesson from Fruteland Jackson, a veteran bluesman who hopped aboard at Maxwell Street. Each of us was issued a harmonica, and, wielding an acoustic axe and a harmonica rack, Jackson taught us to play a basic 12-bar pattern. The trick: for the first bars you suck, and then you blow. As we rolled back to our starting point, the bus resounded with the sounds of blowing, sucking, “dumping” (exhaling) and flourishing big finishes. We got to keep the harmonica!

Did I say one last treat? There was one more. When we got back to Jazz Record Mark, its legendary owner Bob Koester, happened to be there. Mr. Koester was the founder of Delmark records in 1953, the oldest jazz and blues independent record label in America. The great man stood listening as Amanda summed up.

I’ve said it before: as long as I’ve lived in Chicago—20 years now--there’re always something new to discover around every corner. Turns out there’s always something “past” to discover as well.

Now when I’m on the commute home, I can pretend like I’m on that streetcar up to Uptown.