“And what is good, Phaedrus,

And what is not good—

Need we ask anyone to tell us these things?”

—epigraph from Robert Pirsig’s “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance”

*****

In early 2021 I wrote about John Huston’s loving 1987 film adaptation of James Joyce’s The Dead, in which the central character, Gabriel, muses of his loved ones, after spending a warm evening in their company: “One by one we are all becoming shades.” The film has an awareness of basking in the memory of shared experiences with friends and family even as they’ve unfolding, a gratefulness for shared time that can only come from the awareness that the time is running short. It spoke to a feeling in the air. Over the course of the year I lost my friend Jane Nye, who’d been cutting my hair for almost 20 years. I lost my Aunt Pat and my Aunt Lou, both wonderful, community-service minded people, and much-loved. In September, I lost my father, Gary Vincent Pfeiffer.

I didn't devote many words to movies this year, not formally. I simply couldn’t summon the sustained attention span it would have required.

I’m sure I’ll go back to writing about films again at some point. Still, it won’t quite be the same. Whether consciously or not, I always wrote my reviews with my dad as an imagined reader. (My Aunt Lou, as well, to a different extent). I don’t even know that dad ever paid much attention to them, though my mom always reads them. Still, it was often his voice I would hear as I thought about my sentences. I know that dialogue and debate will continue, if I listen closely enough.

Film wasn’t a big part of dad’s life. Still, he’d lived through one of the headiest eras in film history and he wasn’t untouched by it. In fact two of the big ones, Antonioni’s Blowup and Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, had made a big impact on him. He got me videotapes of those two films 30-some years ago as contributions to my cinematic education, and they stoked my budding love for cinema. Moreover, the whole project of criticism and critical thinking, the quixotic separating of the good from the not good, the search for quality, even the notion of that chimerical notion “quality” itself, is one of the many things I learned from him.

So I could do the usual Top 10 thing and write about remarkable films like this year’s two releases from Ryusuke Hamaguchi, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy and Drive My Car. The latter is about the way in which art (in this case theater) helps us connect, or reconnect, with the emotions of experiences—emotions like grief—in ways we might not have even been able to do at the time we were living through them—in a way, that’s the problem of the two central characters in this movie, a theater director and his driver. By allowing us to finally feel, art can move us in way that feels akin to being reborn, or redeemed.

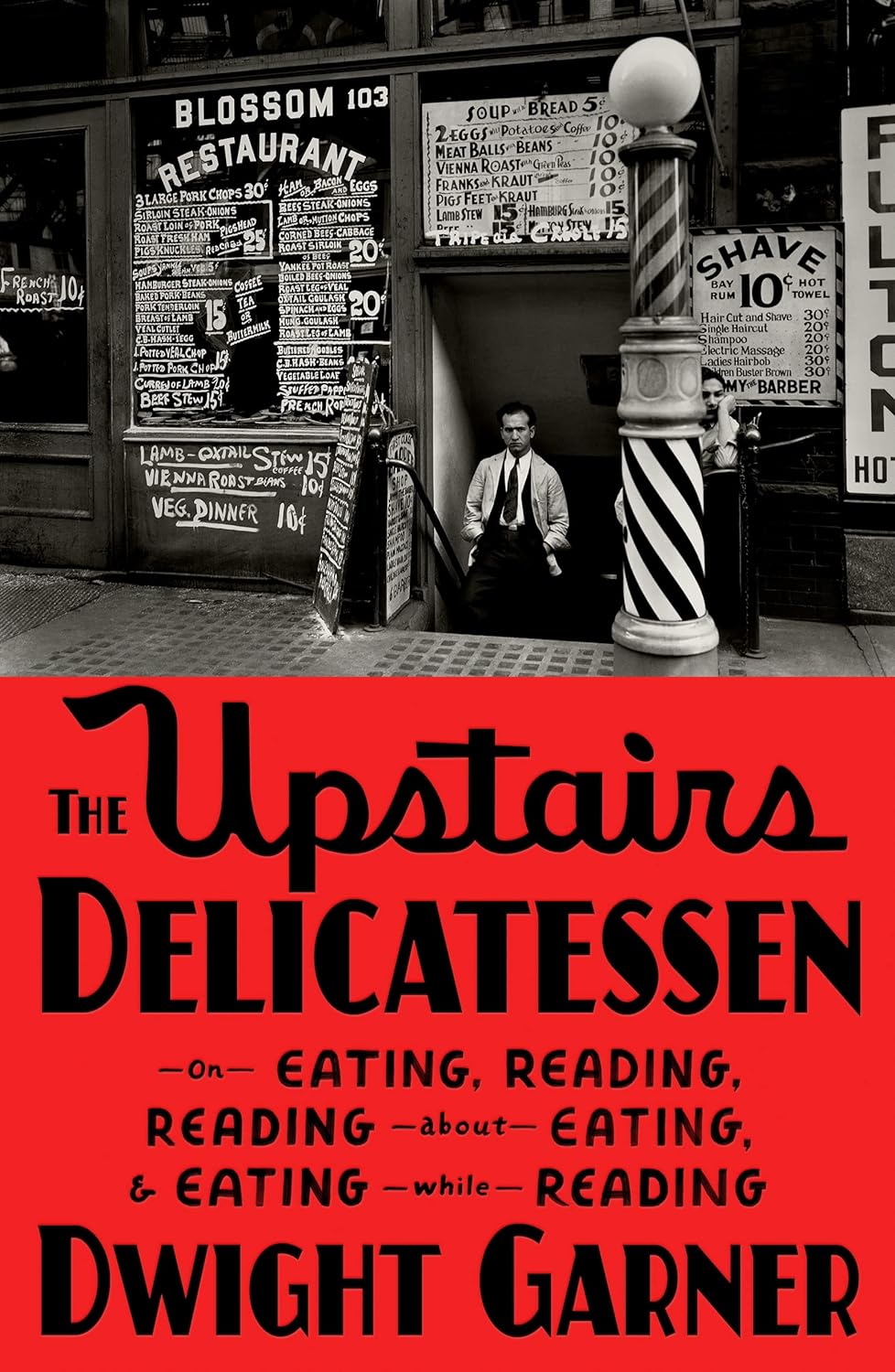

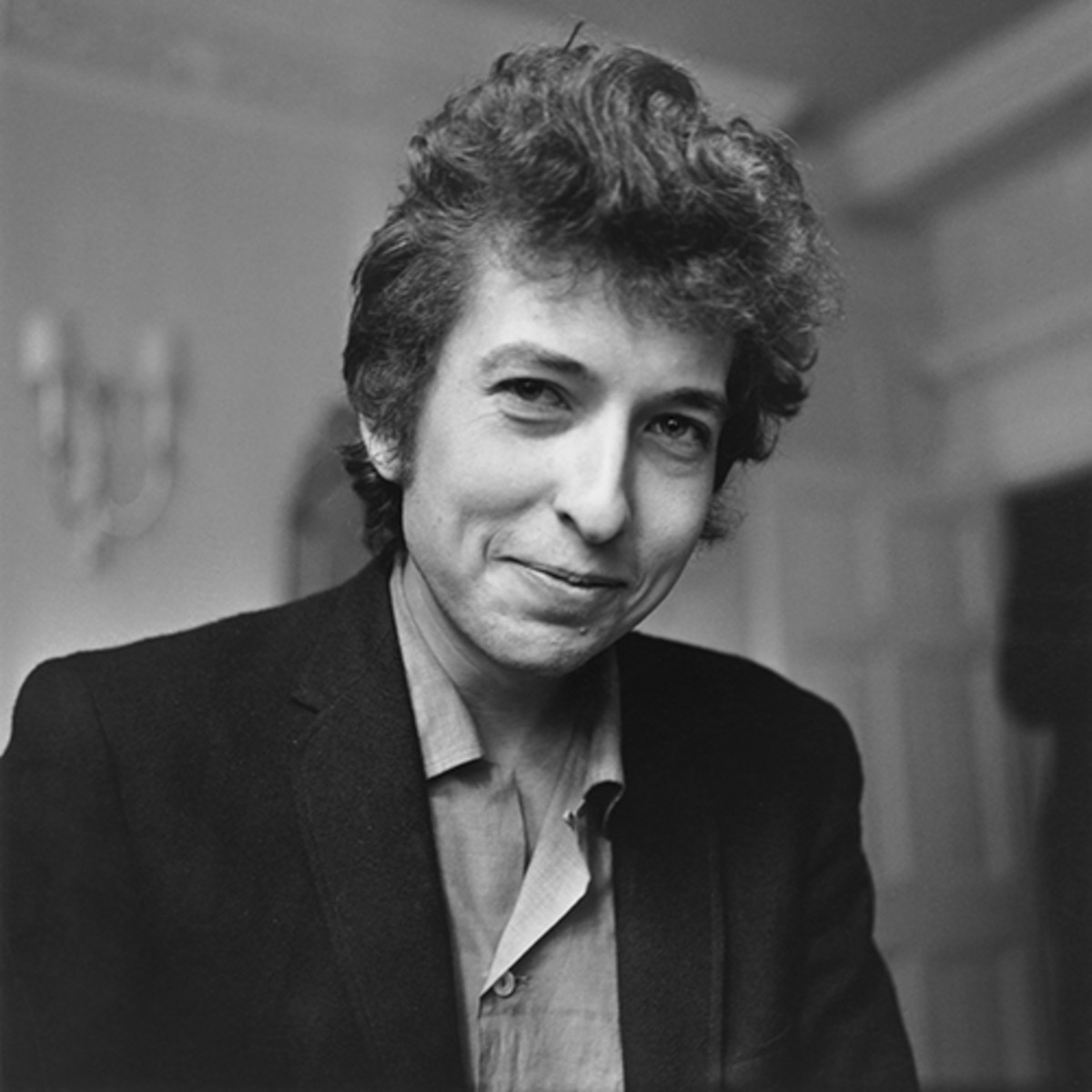

I could write about the year's abundance of music documentaries. 2021 saw new looks at the two most influential rock bands of all time—the two with the greatest range and depth, and perhaps the most impactful on my life. I speak of The Beatles and the Velvet Underground. Peter Jackson’s The Beatles: Get Back, was an immersive eight hours, and each moment fascinating. Todd Haynes’ The Velvet Underground was a look at the cultural renaissance of the ‘60s from a New York perspective, in form an homage to American underground film: it was dedicated to Jonas Mekas. Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson made the transcendent Summer of Soul, which documented “the Black Woodstock.” Alma Har'el's Shadow Kingdom resonated with me especially. Grief is a shadow kingdom, after all. The film was an elegant, witty fantasy of a Bob Dylan performance. You don’t even need a passport to get to the Bon Bon Club in Marseilles: it’s a state of mind.

I could write about the sheer inexhaustible visual delight of the ever precocious Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch or of Paul Schrader’s ongoing exploration of guilt, redemption and Bresson in the Abu Ghraib-haunted The Card Counter and…but no.

Truly, the most important thing I wrote in this or any year was my dad’s obituary, a collaboration with my mom and my sister Amy. In lieu of the usual look back at the year in film, then, I’ll reprint our remembrance here below; after all, he was the reason I write in the first place. Goodbye, dad. I’ll miss you.

****

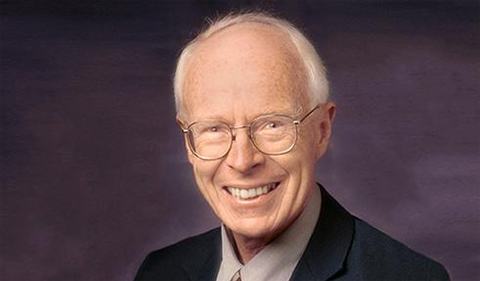

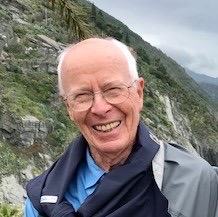

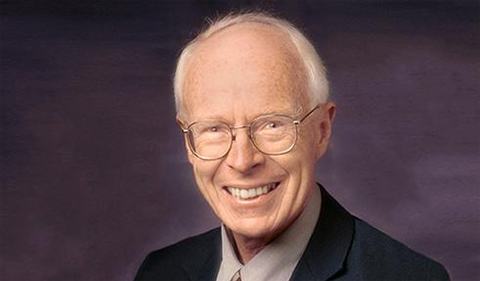

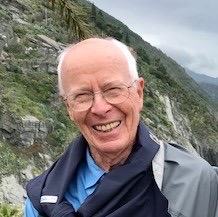

Gary V. Pfeiffer, 81, passed away peacefully at his home in Athens on September 8, 2021. Gary is survived by Barbara, his wife of 51 years; his daughter Amy and her wife Gina; and his son Scott and his wife Karolyn, all of whom surrounded him with love and light in his final weeks. Also surviving is his brother Arden and many beloved nieces and nephews. He is preceded in death by his mother, Doris M. Coates Pfeiffer, and his father, Howard R. Pfeiffer.

Gary was born on February 1, 1940 in Wellsville, New York and grew up in nearby Whitesville. At the age of 12, a chemistry set gifted to him by his parents set him upon the path he would follow for the rest of his life. He graduated valedictorian at the age of 17 from tiny Whitesville Central School, where his aunt, mother, and grandmother all taught. Thus began a lifetime of academic success which came to him as naturally as breathing. In 1961 he graduated from the University of Rochester; he earned his PhD in chemistry from Carnegie Mellon in 1966. After post-doctoral work at Princeton University he came to Ohio University in Athens in 1967 to join the faculty of the Chemistry Department. Apart from a year-long sabbatical at the University of California, Berkeley in 1977, Gary taught physical chemistry and freshman chemistry at OU full-time for the next 36 years. After his partial retirement in 2003, he continued teaching part-time for another seven years, taking full retirement in 2010. He chaired the Faculty Senate from 1999-2001 and served as its secretary and treasurer in other years.

In 1970 he met the love of his life, Barbara, on a ski trip in Blackwater Falls, West Virginia. They were married seven months later. Together, Barbara and Gary saw the world. After raising a family and retiring, their adventures took them across the United States and to places as far-flung as China, Vietnam, Morocco, Australia, Russia, and Peru, to name a few. Gary and Barbara spent a month in both Paris and New York City, two of their favorite cities.

A vigorous and active man, he jogged four miles with Barbara every morning for many years. He was a dangerous tennis player from a young age: his many tennis buddies/opponents always testified to his prowess on the court. Always competitive, he loved games, especially Scrabble, in which he was notorious for pondering his moves for minutes on end.

Gary treasured books and the written word, especially history and science. As much as he loved to read, he equally valued conversation. He was always well-informed, a lively, non-dogmatic, and witty raconteur and debater. For years he was part of a close-knit group of friends known as “the gourmet group,” who would meet at each other’s homes for internationally-themed dinner parties that would range deep into the night.

Gary loved the arts, especially painting. He visited many of the world’s great art museums, and he was a board member of Friends of the Kennedy Art Museum in Athens. He also served for many years as the Friends’ treasurer.

A man of science, he was endlessly curious about the way the world works. As logical, rational and analytical as he was, though, he was just as warm and openhearted: no one was more likely to cry at a moving movie. His living example of how to treat other people will continue to inspire his family every day for the rest of our lives. We loved his smile and we will carry him with us, always.

Gary’s family would like to offer our sincere thanks to the Ohio Health Hospice team who provided us loving care and guidance on Gary’s final journey. A celebration of his life is pending, due to COVID. if you wish to honor Gary’s memory, please donate to your favorite charity. Among Gary’s favorites were Habitat for Humanity of Southeast Ohio, Friends of the Kennedy Museum at Ohio University, and the Chemistry Scholarship Fund at Ohio University.

Thursday, January 18, 2024 at 06:32PM

Thursday, January 18, 2024 at 06:32PM