Hugo

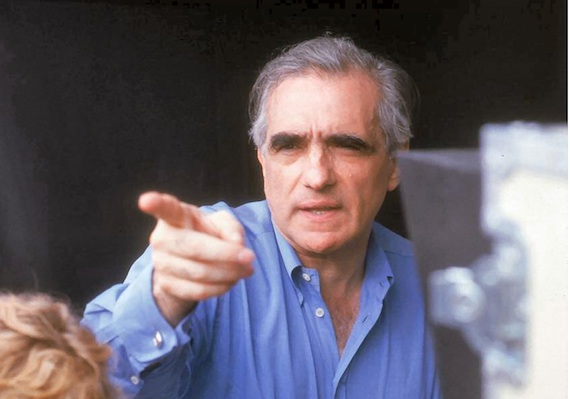

Martin Scorsese can never be impersonal, and this delightful, good-hearted picture, his first childen's film, is no exception: it is a movie about movies. It's Scorsese's first foray into 3D as well. I was curious to see what America's greatest living filmmaker (I was going to put that in quotes, but then I thought, no, let it stand) would bring to the 3D experience (or gimmick, if you want).

Hugo, played by the vivid-eyed Asa Butterfield, is an orphan who lives in the clockworks of a train station in early 30s Paris. He winds the clocks and spies on the shopkeepers and regulars who populate the station. It's quite a little community, rendered in rich detail, as is 30s Paris, often glimpsed at night: sometimes you catch a glimpse of the spire and towers of Notre Dame in the background.

Hugo shoplifts food when he can, as well as spare parts from a stern, bitter toy-shopkeeper (Ben Kingsley). He hopes to use the parts to fix his broken automaton, a clockwork man discovered by his late father (Jude Law), a museum curator. The ingenious machine was made to write something, his father knew...but what? Fixing it was their common project before his death. They were always stymied by its heart-shaped lock, and Hugo is forever hoping to find the key that will unlock its mystery. In this quest he is helped by his new friend, the shopkeeper's bookish, spunky goddaughter, Isabelle (the ebullient Chloe Grace Moretz, who played the lethal pre-pubescent in "Kick-Ass"). Grace Moretz pulls off the English accent so well that I forgot she is American (the characters are French, of course, but as in so many American productions an English accent is used to denote foreignness.)

As for the toy shop owner, I was going to say that he is a man with "a secret past," but I don't think it's any secret by now to reveal that he turns out to be an all-but-forgotten George Melies, the great man of early film, though his identity remains a secret to Hugo and Isabelle. Hugo becomes drawn into his world after Melies catches him stealing parts and confiscates his notebook, which contains his father's drawings and notes on the automaton. They work out a deal where Hugo will work in the shop until it is determined that he has paid his debt. He meets the bitter man's wife (Helen McCrory) and god-daughter Isabelle, who loves to go to the library and introduces him to a librarian (the great Christopher Lee, Dracula in those old Hammer Productions pictures), a vaguely magical figure who directs the kid detectives to a crucial book on film history. It's author magically appears, played by Michael Stuhlberg.

Hugo must at all times stay one step ahead of the Station Inspector, forever on the lookout for scamps. Sacha Baron Cohen gives my favorite comic performance of the year, all puffed-up zealotry and comic menace when chasing the boy or dealing with the malfunctions of the frame mechanism on his leg, wounded in WWI, but reduced to shy stammering in the face of kind Liselle (Emily Mortimer), the flower lady of whom he is a secret admirer. Some of the physical comedy and manic chases might remind you of Malle's "Zasie Dans Le Metro" or even the M. Hulot films.

By the way, word of warning to my hordes of acid-dropping readers (and you know who you are): you don't want to be on LSD for the moment when Scorsese gives us a close-up of Baron Cohen and then his head, several-stories-tall, slowly emerges from the screen until he seems to be putting his nose right up to yours. Or maybe you do.

I was actually just thinking of Scorsese last week because I'd attended a special showing of 1978's "The Last Waltz": it's a film I watch at least once a year on video, but I'd never seen it on the big screen. As always I got a kick out of his persona as interviewer: the rapid-fire speech, the comic intensity. That was the era when he was making essential films, movies that defined their times. "Hugo" doesn't, and that's okay: the very greatest artists have a moment when they somehow both evoke and sum up their time, and then they carry on, making a life, making new things--some of them great--though never again being quite so in touch with the zeitgeist. By then it's somebody else's turn, you know.

Anyway, I've been at the theater for each new Scorsese picture, year in and year out, since "Goodfellas" in 1990. Some I've liked more than others, but "Hugo" may be the first Martin Scorsese picture that could be described as "wonderful". Probably because it's the first to be told from the point of view of a child, usually more the purview of someone like Spielberg.

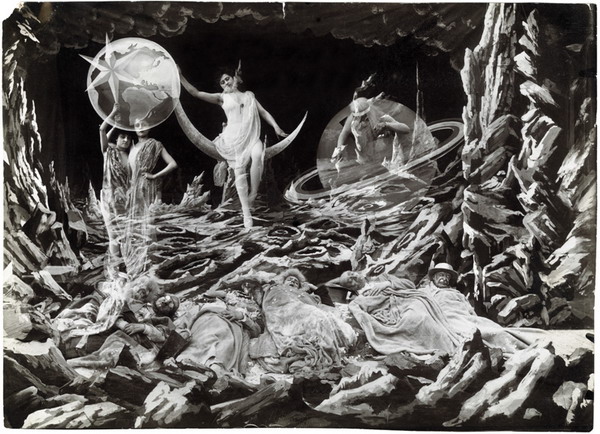

And of course as a student of film I've long been interested in George Melies. In film texts he's almost always discussed in relation to those other pioneers of early film, the Lumiere Brothers: they used the new medium to record reality, while Melies used it to produce striking fantasies. It's the dichotomy, we are taught, that still defines film aesthetics to this day: realism vs. special effects.

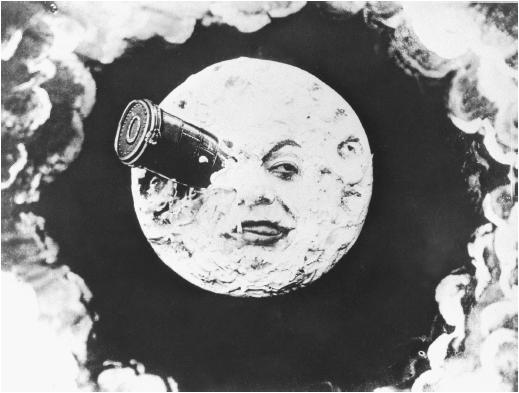

In "Hugo" we get to see the iconic 1895 footage by the Lumiere brothers: the train arriving at the station, the workers leaving the factory. We also see real and recreated moments from Melies films like "A Trip to the Moon" (1902), with its iconic image of the man in the moon with a rocket ship in his eye. Quite sly sleight-of-hand on Scorsese's part, to get the asses of modern audiences into the seats with the promise of the most cutting-edge modern technology and special effects, and then have them marvelling at films made in the turn of the century. I couldn't help but wonder what Melies would think if he was somehow able to see "Hugo" in the state-of-the-art theater in which I was sitting. I've got to think his mind would have been blown.

Scorsese uses 3D to give a modern audience the sense of wonder that greeted early film audiences. Fish float before your eyes (Melies shot through an aquarium placed in front of the camera to get the effect). His studio, made of glass to let in the light, is strikingly rendered, a beautiful crystal palace. When the kids sneak into the movies, Harold Lloyd's "Safety Last" is showing. They gasp at Lloyd dangling from the hand of the clocktower; later Hugo will do the same, and we gasp. And Scorsese stages his own "train coming into the station" moment that is violent enough--and, in 3D, immediate enough--to have me, if not throwing up my hands just like viewers of that 1895 Lumiere film, at least rearing back in my seat.

The best way to experience "Hugo" is to see it on a massive screen with surround sound, because Scorsese puts you inside the clockworks, into its crawlspaces and passageways, and you can see up and down through its grated iron tiers and hear the gears ticking behind you and around you. You are suspended along with the kids when they climb down to wind the clock that dangles from the station roof. There's an echo of "Vertigo" in a chase to the top of the clock tower where the camera looks straight down; I was kind of hoping Scorsese would give us a 3D version of Hitchcock's simultaneous zoom-in and pull out, but he doesn't. He knows Hitch did his shot that way for a reason.

The good script by John Logan, from the book "The Invention of Hugo Cabret" by Brian Selznick, sounds a good theme for the children watching: happiness comes from finding your purpose and then doing what you do. It's so simple, and yet adult viewers know something the children in the audience can't: there's nothing simple about it. So the film manages to package some existentialist ideas in a way kids can think about, another neat trick.

I remember the time years ago when my cousin Matt, a fellow film buff, brought over an actual reel of celluloid of Melies' "A Trip to The Moon" to show my sister and me. I have no idea where he got it. He threaded it into the projector and we darkened the lights, lay down on the floor and turned our eyes to the screen. I remember the sound of the projector whirring. It captivated, just as it had in 1902: a dream being dreamed in the daytime.

Rating: ****

-- December 6, 2011

Key to ratings:

***** (essential viewing)

**** (excellent)

*** (worth a look)

** (forgettable)

* (rubbish!!)

Scott Pfeiffer | Comments Off |

Scott Pfeiffer | Comments Off |