BEAT THE DEVIL, Redux

Scott Pfeiffer

Scott Pfeiffer  Wednesday, June 28, 2017 at 09:01AM

Wednesday, June 28, 2017 at 09:01AM  "In the South of France, anything is possible!" Andre Bazin once declared. That is the setting for the 1951 novel Beat the Devil, and though John Huston's one-of-a-kind, endlessly funny film version moves the action to Italy’s Amalfi coast, it preserves the anything-goes spirit. Now, "the longest running cult favorite in history," as James Monaco called it, is back, thanks to a new 4K restoration, in all its strange, uneven glory. Even today, people exist who can recite swaths of its dialogue as if it's verse.

"In the South of France, anything is possible!" Andre Bazin once declared. That is the setting for the 1951 novel Beat the Devil, and though John Huston's one-of-a-kind, endlessly funny film version moves the action to Italy’s Amalfi coast, it preserves the anything-goes spirit. Now, "the longest running cult favorite in history," as James Monaco called it, is back, thanks to a new 4K restoration, in all its strange, uneven glory. Even today, people exist who can recite swaths of its dialogue as if it's verse.

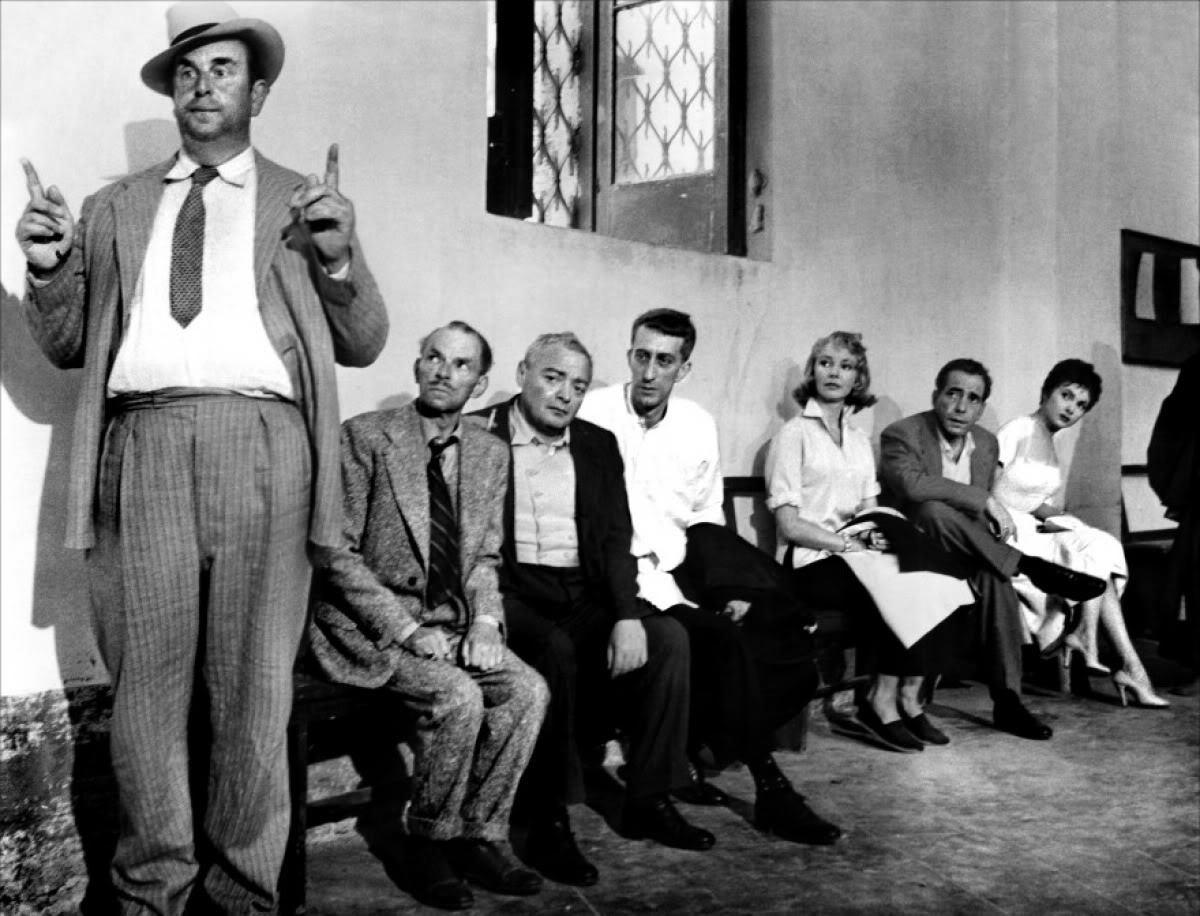

Humphrey Bogart plays a middle-aged roustabout who, according to the novel, once rather had the reputation of a "second Lawrence." Those were the "good old" prewar days; now, the social order is upended, the Atomic Age looms, and he is reduced to being a hired agent of "the committee"—a a comic little crew, as would-be international men of intrigue go. As Roger Ebert notes in his Great Movies essay on the film, we smile simply upon sight of the great character actors comprising this seedy gang, staking everything they've got on a plot to make a fortune in the illegal postwar uranium rush in British East Africa: Peter Lorre, Robert Morley, Ivor Barnard, and Marco Tulli.

There are other stranded Africa-bound travelers. Jennifer Jones, hair dyed blonde, plays a woman who, shall we say, "uses her imagination rather than her memory." (She tells lies that are "truer than true," as she puts it). That is, she's a blithe fabricator—right up until the great moment when she finally, deliciously, tells the truth. She's married to the silly Edward Underdown, a stiff-upper-lipped Englishman whose confidence about the way the world works marks him as a man of the old world—and something of a fool in the new one.

Underdown is much admired by Bogart's wife, the wonderful Gina Lollobrigida, playing an Anglophile. ("Emotionally, I am English," proclaims the uber-Italian actress). Jones, in turn, carries a torch for Bogie. The restoration removes some censorship, but even so, the movie is not nearly as pungent about this double infidelity as the novel. That is to say, with the exception of a restored, and scandalous, shot featuring Lollobrigida's cleavage. (The old version faded out before her bust could fill the screen.)

The novel was the creation of Claud Cockburn, the great Scottish/Irish journalist and communist. (The credited "James Helvick" was a Cold War sobriquet: the novel and film appeared at the height of the blacklist and McCarthyism.) Every week in the '90s I would eagerly pour over Claud's son Alexander's mighty two-page column in The Nation, "Beat the Devil," named in homage. Huston, a friend of Cockburn's, was keen to turn the novel into a film, yet he turned up in Ravello, where cast and crew had convened, with more enthusiasm than script. (Treatments by Cockburn himself, as well as by Anthony Veiller and Peter Viertel, hadn't work out.) David O. Selznick, Jennifer Jones's husband, thought to bring in the hot and controversial young writer Truman Capote. (In the Chicago Tribune, Michael Phillips noted the sly joke that Lorre's hair is dyed to look like Capote's.)

Capote's great innovation was to turn the material into a campy parody, making the picture a sendup of '40s adventure movies. Pauline Kael, a big BEAT THE DEVIL fan, went so far as to say it "finished off" the form, much as THE LONG GOODBYE later would the private eye genre. Actually, I think Capote could've taken it even further in the direction of parody—cf. S.J. Perelman spoofing Raymond Chandler. And didn't the '40s pictures themselves sometimes have a knowing wink? A few scenes feel like they're not sure if they're straight; as Kael noted, Bogie doesn't seem always to be in on the lampoon.

As the set became a party, Capote legendarily made up the screenplay as he went along, beating a daily deadline, with Huston handing out the pages to the cast right before filming. Upon examination, however, much of the funniest dialogue is right there in the Cockburn novel, including Lorre's line that many Germans in Chile have become called "O'Hara," as well as Lollobrigida's quoting of the novelist George Moore, cited approvingly by Ebert. ("I believe," he writes, that Moore "has not been quoted before or since in any movie.") On the other hand, some of the most-loved lines seem to be Capote's, including Lorre's famous "time" speech. On the other, other hand, Lorre and Morley sometimes made up their own dialogue on the spot. Whatever its tangled provenance, it must be said that the "screenplay," as it plays on screen, is a witty and cagey adaptation, sparkling with "bon mots."

For the first time in decades, the visuals sparkle as well, thanks to the new 4K restoration overseen by The Film Foundation and Sony Pictures's Grover Crisp. Its limpidity will shock you if your previous viewings, like mine, were on scratchy VHS. The restorers went back to the original 35mm negative. (Asking if we couldn't have a nice 35mm print alongside the DCP as part of the restoration feels almost churlish, or like one of those existential questions). Freshly scrubbed, Oswald Morris's gorgeous black and white cinematography gleams with granular detail and texture, as well as an almost 3D sense of depth. A shot framing Bogart and Jones canoodling high above the Tyrrhenian Sea is breathtaking, almost vertiginous: when the camera pulled back and up, I felt I might fall right through the frame. In my notes I have, "the view is stunning"; later, when I looked up what Farran Smith Nehme wrote at Film Comment, I was pleased to see she felt the same.

The restoration removes Bogart's narration, and thusly the movie's flashback structure. It runs roughly five minutes longer now. Much of the added material restores Jones and Underdown's stroll from near the beginning of the novel; fans of the book will be glad to have restored to celluloid Jones discussing her Spanish nurse, and why it's important to spit first. A Rita Hayworth pinup in the office of the "Arab inquisitor" (Manuel Serano, with hookah, naturally), previously obscured by a shadow, can now be seen in all its glory. The laughs everyone had making BEAT THE DEVIL are contagious: after 64 years, it's still a hoot. By the end of this freshly showered version, my face ached from smiling.

John Huston's BEAT THE DEVIL (1953, 95 min, DCP Digital) plays at the Gene Siskel Film Center from June 30 through July 5. Check Venue website for showtimes.

Reader Comments