If by "favorite" you mean a picture I can watch anytime with pleasure, then here are a handful. What we have here is a snapshot of a river. It won't be the same the next instant you look. And yet it's a river worth gazing into, if only to see your own reflection double-exposed on the rushing flow of film history.

I'm glad a blog is not a written-in-stone proposition. After all, I still hope to discover my "favorite" movie tomorrow.

Plus, most of my favorite directors aren't here. I found myself flagging when I tried to pick one favorite Hitchcock, for example. It's been a pleasure going through his career again with Karolyn for our off-and-ongoing Hitchcock Home Video Festival. Next, we plan to do the same for Orson Welles.

(And then, she threatens half-seriously, the oeuvre of Adam Sandler(!). Ah well, watching anything is a pleasure, so long as her head is on my shoulder.)

In no particular order, then:

The Godfather Parts I and II (Coppola, 1972 and 1974) All the pistons of a movie--acting, writing, directing, cutting, theme, cinematography, sound design, music--fire at their highest level here. This is one of the pictures that made me fall in love with movies in the first place. (I think of Parts I and II as two chapters of one epic.) From scene to scene, it takes your breath away. Pacino's depiction of the hollowing-out of Michael Corleone is chilling, as is the way Coppola stages it, so that we're in Connie's shoes by the time he finally turns to her with those empty, dead eyes. Part I is electric pulp; Part II has the Fredo-kiss against the backdrop of Castro's revolutionary troops marching into Havana. Oh, and it features the great acting teacher Lee Strasberg in an unforgettable cameo as a mob boss. Serene but with a core of steel, endlessly wily, Strasberg's boss must have been a touchstone for Giancarlo Esposito's brilliant turn as Gus on "Breaking Bad."

Mulholland Drive (Lynch, 2001)

Hits the movie trifecta: mind, gut and loins. A sensual, guilty fever-dream. Laura Elena Harring is the woman who's lost her memory. Naomi Watts is the aspiring starlet. It casts a spell, but then it's all about being spellbound, mesmerized by the feverish power of the movies themselves. Theories about what it all means are great fun, but in the end the film is a handful of magic, an illusion: if you ever really did turn that blue key and pop open that blue box, wouldn't you be like the boy who cut open his drum to see what made it bang? David Lynch orchestrates color, identity, and layers of movie references into the ultimate movie about Hollywood. It shows you what's rotting out on the backlot.

Mean Streets (Scorsese, 1973) The drums of "Be My Baby" announce where it's taking us: back to the energy of the streets, urban romance, Catholic pageantry. Martin Scorsese's picture introduces us to his neighborhood, New York's Little Italy in the early 70s. It's insular, largely untouched by the tumult of the 60s, a tumult which Scorsese comically lets hover around the periphery, from Vietnam (a troubled vet) to the counterculture (girls from the Village). That said, it's funny to think about what a huge influence "Easy Rider" was on it. (Not to mention Kenneth Anger's "Scorpio Rising" and Godard's "Breathless"). It’s not about gangsters so much as neighborhood guys. In fact, the only one of the guys who seems to take himself really seriously as a mobster is depicted as an asshole. Robert De Niro's slo-mo entrance to the bar to "Jumpin' Jack Flash" had drama and menace, song and image electrifying each other. Harvey Keitel and De Niro make every move with a certain energy, and so does Scorsese's filmmaking. While his truly bravura cinema would come later, the energy of this one sent me reeling. I've never recovered.

Monty Python's The Meaning of Life (Jones, 1983) This stands for all those moments in my life when Monty Python has made me laugh so hard I couldn't breathe. The astonishing opening sequence, in which elderly insurance agents mutiny against their new corporate management, then tear an entire London office building from its moorings and sail away to do battle on "the high seas of international finance," stands for all of Terry Gilliam's visionary movies like "Brazil" that fired my imagination. There's something deeply pro-human in the way the Pythons tweak all those dehumanizing areas of life that most need it. Their surrealism prepared me for Bunuel. I am happy to live in a world that includes Terry Jones and Gilliam, Graham Chapman (RIP), Eric Idle, Michael Palin, and John Cleese. "Every sperm is sacred..."

Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love The Bomb (Kubrick, 1964) The lighter side of the end of the world. The genius of Peter Sellers, as directed by another genius, Stanley Kubrick. The great mad mugs of Sterling Hayden and George C. Scott. It was the height of Cold War madness. But it's not dated: the Bush administration was chock full of people like this. I love Slim Pickens in Kubrick's fetishized B-52: "I've been to one World's Fair, a picnic, and a rodeo, and that's the stupidest thing I ever heard over a pair of headphones!" "I'm gonna get them doors open if it harelips everybody on Bear Creek!" A friend once told me that before he passed, her grandfather watched this movie every day. He'd growl to her, "The more I watch this, the weirder it gets." I've got to agree with the old boy's assessment.

Before Sunset (Linklater, 2004) Richard Linklater and his two leads/co-writers, Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy (sigh), make a perfectly shaped, jewel-like coda to 1995's "Before Sunrise." In "Sunrise," a young American man and a young French woman met on a train, spent a day and night together in Vienna, and, without exchanging any contact information, vowed to meet again in six months. "Before Sunset" takes place nine years later as they meet again for the first time since their initial encounter. It follows them around Paris for 80 minutes of “real time,” and every one of those aching seconds rings true. It's about being in the moment, enjoying the passage of time in the presence of another heart, even as it bears you inexorably along to the end, as it must. Let us not talk falsely now: the hour's getting late.

Alphaville (Godard, 1965) Anna Karina. (Sigh.) Eddie Constantine has one of the best noir mugs in the history of the movies. Paris at night is a sci-fi world, captured by the great cinematographer Raoul Coutard. You can watch it just for the beauty of his black and white photography, with its hard gleams and soft glows, its inky black shadows punctuated by streetlamp flares. It is here that Jean-Luc Godard's visual and narrative poetry is most deeply felt, here that he sings of Paris at his most elegiac and swooning. I don't know what it all means, but I know how it makes me feel.

8 1/2 (Fellini, 1963) This is another that made me fall in love with cinema in the first place. It's shot through with joy and humor. Movies are dreams; and yet, along with Lynch, Bergman and Maya Deren, Fellini is one of the few directors who can really get down on film the feel of a dream. So many magical moments: Guido's dream of his warm, happy childhood in that Italian farmhouse. Claudia Cardinale appearing like a vision and offering him the healing waters. That joyous Nino Rota score. The moment of honesty and self-acceptance, when, before taking his wife's hand so that they too may take their place in life's rich pageant, Guido pleads, "Life is a party, let's live it together...Take me as I am, if you can. It's the only way we can try to find each other."

Plus a series:

The Up Series (Apted, 1964 to the present) This series taught me more than any other film. It reminds you of what might yet turn out to be film's most salient power: its ability to record reality. In 1964 Michael Apted handpicked a group of seven-year-olds from the poles of the UK’s social spectrum to appear in a short black and white documentary called “Seven Up.” Every seven years since, Apted has revisited the “Uppers” (as he affectionately refers to them) to document their unfolding lives. As they grew up, we watched them grapple with all the great themes: love, death, faith, dreams, work, happiness, illness, the meaning of life. Though they were chosen to represent their class, over the years the subject of the series has become these people as individuals. Time collapses, and we see the child in the adult, and the adult in the child.

Plus a documentary:

Forever (Honigmann, 2006) “We too were men joyful and weary like you, and now we are lifeless, we are only earth, as you see. All that is created must end. All, all around us must perish.” (Michelangelo). “Forever” is an extraordinary documentary about life, death, and art by Heddy Honigmann. Honigmann took her camera into the famous Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris, where some of the world’s greatest artists rest. She interviewed the people who come from around the world to visit them. As the men and women talk about their favorite artists, their faces express what they never quite come out and say: art makes life worth living. As Honigmann juxtaposes shots of Maria Callas’ grave with a clip of Callas singing--so alive, so joyful--I finally understood. The singer is dust, but when we commune with the beauty she made--we who yet feel joy and sorrow—then the artist sings through us. Then is eternity attained.

Plus three rock & roll films:

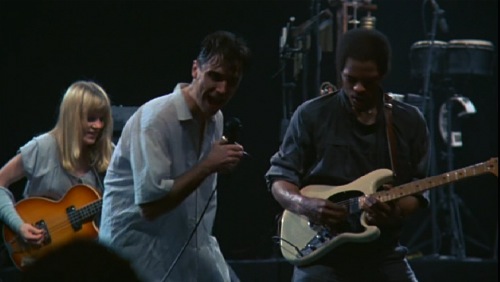

Stop Making Sense (Demme, 1984) This has always been a benchmark for me: here is the level of energy and intensity and joy that is possible in life. It's a metaphor for how a life worth living should be lived. Think of Bob and Judy: "They might be better off, I think/The way it seems to me/Making up their own shows/Which might be better than TV." Jonathan Demme's movie is a vision of community: black and white, men and women. It's a sustained miracle of filmmaking and performance and stage conception coming together to create moments that can only be described in one way: transcendence. And that's what I'm looking for at the movies.

The Last Waltz (Scorsese, 1978) I love Scorsese's compositions, the camera moves, the rhythm of the cutting. Rick Danko sings "It Makes No Difference" into the dark, and Garth Hudson's sax makes the night come alive with warmth. Levon Helm hated this picture, true. But he's so great in it, fierce and tender. Elegiac, celebratory, the movie glows with warmth and camaraderie. There are deep, subconscious levels on which it is resonant with Vietnam and the Civil Rights movement. As Robbie Robertson punches the air into "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," they wrest triumph from the end of an era.

Once (2006) The guy and the girl meet on the streets of Dublin. Each is a musician, each at a crossroads. I love watching them watch each other in that great music-store scene when they play together for the first time. I’m a sucker for the sound of men and women singing together, the powerhouse roar of Glen Hansard intertwining with the quavering tremelo of Marketa Irglová. The raw emotion of the music they make together threatens to shake the film off its sprockets. It can also be exquisitely gentle and sweet. Hansard, Irglová, and director John Carney have made one of the great music films. I think of that great scene in the pub where everyone around the table takes turns singing. We get a sense for how music and food are the ties that bind community, family, generations.

[With apologies to "Repo Man," "Paris Texas," "Wings of Desire," "Chungking Express," "Persona," "The Big Sleep," "Casablanca," "My Dinner With Andre," "Don't Look Back," "It's a Wonderful Life," "His Girl Friday," "Singin' In The Rain," "Blue Velvet," "Inland Empire," and the cinema of the nation of Japan.]