My hometown and the wheel of time. WOUB publishes my Elvis Costello review.

Thursday, August 18, 2011 at 01:38PM

Thursday, August 18, 2011 at 01:38PM I write to you from my hometown of Athens, Ohio, deep in the verdant valley of the mighty Hocking River. Seen from car windows, the buildings where I went to high school, middle school, elementary school scroll past. There's the house where I stayed as a college student. Every glance here triggers an association. There's where I shot a video about fishing in the headwaters of the Hocking for an OU class on anthropological film. I run into an influential high school teacher, Pete Lalich, at a local bookstore, and like Proust biting into his madeleine I go rushing back, a 40-year-old man become 16 years old again.

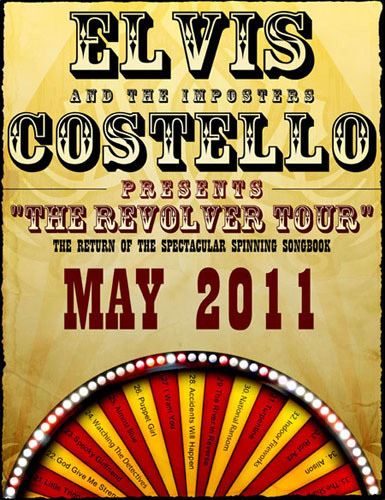

Coincedent with my visit the local public radio station, WOUB, has launched a website under the auspices of Bryan Gibson, my old comrade and fellow snare drum in the AHS marching band percussion section. They've seen fit to publish my comments on my evening at the Chicago stop of Elvis Costello's Spectacular Spinning Songbook tour. The wheel spins, landing on the very first time I saw him in Athens in 1989, coming round again to where I began.

Georgia O'Keefe for free: Wednesday afternoon at the Art Institute

Thursday, August 11, 2011 at 11:03AM

Thursday, August 11, 2011 at 11:03AM Popped over the the Art Institute on my lunch break. It was Free Wednesday and I had taken it into my head that my eyes needed to see the Georgia O'Keefe collection. Free Wednesday or not, I still had to queue up for a ticket. The line was out the door and down the street, but it moved pretty quickly.

I came upon her massive "Sky Above Clouds IV" quite by accident. It's at the top of a flight of stairs that I had hoped led to the O'Keefe gallery. It did not. Still, it's the journey, isn't it?

The card revealed that she finished this in 1965, at the age of 77. It was inspired by airplane trips she took in the 50s. She worked on it in her garage. Though it was scheduled to be shown in San Francisco, they couldn't fit it through the museum doors. It's resided in Chicago ever since.

The bottom photo makes it look smaller than it is. The sense of distance is illusory: it's taken from a landing and the painting is actually across the way on the opposite wall.

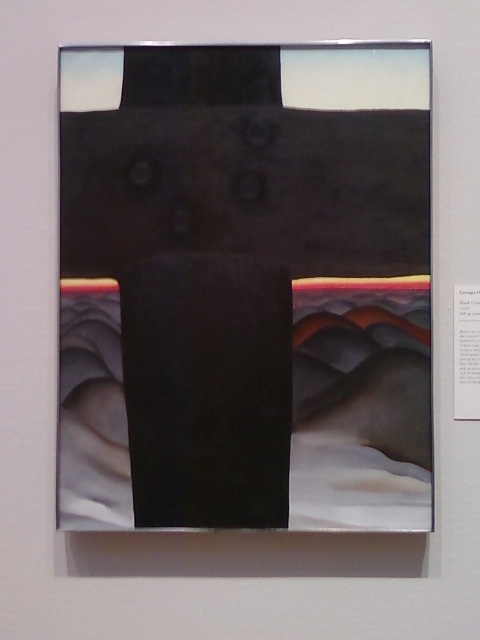

After going down some steps and up others, and wandering temporarily into the new Modern Wing and admiring its sunlit Griffin Court, I eventually located the O'Keefe gallery. Here's "Black Cross, New Mexico", painted during her first summer in the Southwest in 1929.

And "Yellow Hickory Leaves With Daisy" (1928).

Here we have "Peru--Macchu Picchu, Morning Light" from 1957 on the left, center bottom is "Spring" (1923/24), center top "Road--Mesa with Mist" (1961), on the right "The White Place In Sun" (1943).

"Cow's Skull With Calico Roses", 1931. Makes me think of our family reunion in Taos, New Mexico in the summer of 1991.

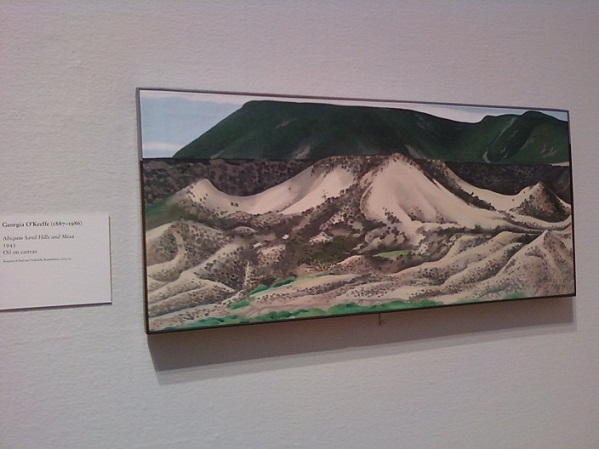

Here's "Abiquiu Sand Hills and Mesa" (1945).

I don't have anything deep to say about these paintings, really, only that it makes me happy to live in a town where I can stroll over and spend an enjoyable lunch hour looking at them.

Movies About Movies class, Part II: "Barton Fink" and "the life of the mind": The Writer in Hollywood, hellhound on his trail

Monday, August 1, 2011 at 03:51PM

Monday, August 1, 2011 at 03:51PM

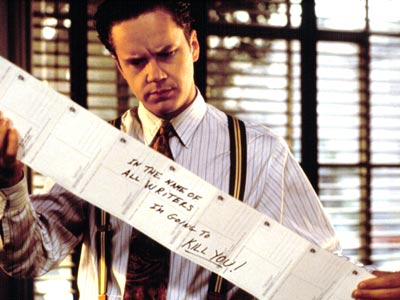

Having dispensed with the Star, the first subject of their “Hollywood Reflected: Movies About Movies” summer class, at the end of June, "Filmspotting" co-hosts Adam Kempenaar and Matty Ballgame pushed onward into the next: the Writer. Once again coming up with an ace three-movie run to explore variations on a theme, they showed “The Player” (Altman, 1992) on June 29 and “In a Lonely Place” (Ray, 1950) on July 6, culminating on July 13 with "Barton Fink" (Coen brothers, 1991). Even though I'd seen all three before, the class never failed to open up these films for me.

The heading for this unit was "We're only interested in one thing... Can you tell a story?" But the overall theme that emerged was "compromise". How much are you willing to sell out? The conflict tearing the Hollywood writer apart is the artist/hack dichotomy. For a "real" writer, writing for Hollywood was seen as prostituting one's self, of being essentially a "popcorn salesman". Movies were considered a mass, commercial, low art.

They harbored a kind of unspoken contempt for the mass audience as well, even as they professed to yearn to see a society organized in the common man's interest. Hovering in the wings at many points in this unit was the spectre of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and its witchhunt against communist subversion in Hollywood, the blacklisting that destroyed the lives of so many screenwriters and actors.

Compromise with formula, compromise by naming names. Guilt and angst and shame plague these writers. As does violence, as Adam pointed out, all of it adding up to a rabid hellhound of spiritual and physical immolation.

Matty kicked the unit off with a lecture explaining that it's not quite right to say writers have absolutely no power in Hollywood--better to say that they've got less than none. (He even gave us an equation showing the precise percentage of power they've got: .000001%, or something like that). The top rungs of the ladder are occupied by "genre", "studio", "star". "Script" comes way, way down down near the bottom. The writer has no creative control. He or she is always beholden to another's vision. He took us through the process of getting a script to the screen, from treatment through spec script to "the pitch" to the working script, which is what actually ends up on screen. By the time it goes through this process, vetted by readers, "fixed" by script doctors, all troublesome traces of creativity and originality have been removed. They illustrated the process with a clip from "Adaptation", with Nicolas Cage playing a sweating Charlie Kaufman-type writer explaining to a mystified exec (Tilda Swinton) his vision of a formula-free movie, and a clip from "Sunset Boulevard", in which the writer declares himself a "person of no consequence".

Then it was time for the night's feature, "The Player". I hadn't seen it since it came out, but certain gestures of Tim Robbins' slick writer's executive--the way he leans back on a couch, resting his arms over the length of its back and fixing his girlfriend with a level gaze--have never left me. (She's a story editor, played by Cynthia Stevenson). Prior to the screening, Matty enlisted a few classmates and me to act in an Altman overlapping dialogue scene. We each were given something to say--the alphabet, say--and then Matty orchestrated it a la Altman, conducting us with his hands as though we were an orchestra, a fun demonstration of the music of an Altman scene.

"The Player" is about the new Hollywood versus the old studio system. Studios have become just another division of multinational conglomerates (20 years down the line, that's why we get things like "Transformers 3", Matty remarked). And yet, studios still see some profit to be made in glorifying old movies, as we see in the scene where Robbins announces a film preservation fund at a gala reception. Throughout the film, posters and postcards evoke classic Hollywood movies (often with rather too on-the-nose commentary on the action, e.g. "They Made Me a Criminal" with John Garfield and the Dead End Kids).

There's a scene in which a new exec angling for Robbins' job (Peter Gallagher) makes the case at a meeting that you don't even need the writer. Just pick out a headline and I'll give you a story, he says, tossing a newspaper around the room. "Mudslide in Chile" becomes "triumph over tragedy".

In the post-film feast of reason and flow of soul--i.e., the discussion period, to which I always contribute some mumbled, throw-him-a-life-preserver sort of remarks--we kicked around some ideas. We talked about the function of that famous opening tracking shot on the Hollywood lot. It makes you continuously look at what you're seeing in a new way, now as an insider, now as an outsider. Adam suggested that the way the writer dies drowning in a puddle might be a rhyme with the writer floating in the pool in "Sunset Boulevard". He made an interesting point about the painter with whom Robbins' character takes up (Greta Schacchi): she never shows her work. Here Altman might be saying that the only way truly to make art is to eliminate the audience. (This resonated with an idea we'd explored in the section on the Star: to whom do you sell your soul? The audience.)

A week passed and class-time rolled around again. As a warm-up to the night's feature, "In a Lonely Place", we watched a clip from "The Bad & The Beautiful" (Minelli, 1952) with Kirk Douglas and Gloria Grahame (whom we'd see again in the night's main attraction), in which Dick Powell's writer eyes warily Hollywood's seductive call. They also ran a clip from 1938's "Boy Meets Girl", a comedy with Jimmy Cagney and Marie Wilson. Cagney and Pat O'Brien play a Hollywood writing team. What do we glean about Hollywood screenwriting from the scenes where we watch them brainstorm, Adam asked? The characters are not multi-dimensional; it's all plot-driven, artificial; genre takes primacy. (Revealingly, Cagney's character states he wants to write a novel so he can write “real people, not a formula”).

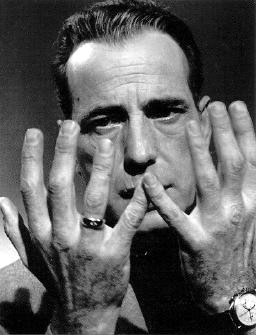

And then it was time for Bogie's very personal "In a Lonely Place", directed by Nicholas Ray (hero to Godard and the French New Wave) and produced by Bogie's own production company, Santana Productions. It finds him playing the volatile Dixon Steele, a writer unable to control the rage and violence that ocassionally possesses him. He exists on a spectrum of male behavior where manly qualities such as "decisive" and "assertive" (it's not for nothing he's named "Dick Steele", Adam offered, to Matty's derision) cross the line into "domineering" and "your girlfriend's walking on eggshells because she's afraid you're going to kill her."

(The characters live in a hacienda-like courtyard very much like the one in "Mulholland Drive". Funny, for some time I'd been sifting through the half-forgotten cinematic detritus in my head: what old movie was it with the courtyard that Lynch seemed to reference in his Hollywood dream? As "In a Lonely Place" opened, I realized it was this one. I'd forgotten I'd seen it).

Guilt defines Steele. Adam tied it into the guilt the liberal Bogie might have felt for distancing himself from the blacklisted Hollywood 10, after having first famously taken a First Amendment stand against HUAC. At the time of the film's release, the 10 were cooling their heels in prison for essentially telling HUAC to kiss their asses. The passionate Matty, a volatile man himself (in that great spirit-of-the-dialectic sort of way) chafed at something in Adam's analysis, and there ensued an entertaining round of banter/recriminations between the co-teachers.

Adam made an interesting point about what fascinates him about this film: Steele is so destructive, and yet the essence of an artist is to create. He commented on the great scene in which Steele imagines a murder for his dinner hosts, inhabiting the psychology of both killer and victim, eyes shining with glee: that's a demonstration of great writing, Adam said. He called our attention to the way Ray lit Bogie's eyes in the scene: he reckoned it inspired the rear-view mirror crazy-eyes shot of Travis Bickle. He talked about the way the movie subverts the Hollywood Ending, which must always be happy. (Well, not only happy: it can also be tearful in a certain kind of way.) This ending dares to be bleak in a way very rare in Hollywood.

Another week passed and it was time now for the Coen brothers' "Barton Fink", which I hadn't seen since it came out 20 years ago. I'd forgotten how funny it was. (Michael Lerner cracked me up as a raving Jack Warner/Louis Mayer hybrid.) Like "Mulholland Drive", the movie that capped our three-film look at the Star, “Barton Fink” is a surrealist trip through a psyche in distress. Fink made his deal with the devil and once again all those Hollywood fears and fantasies come flailing around. Here was Hollywood as Hell, manifest as a room in the Earle Hotel.

I remember being a "Fink" fan at the time of its release, but only in the sense that I liked anything "weird" when I was 19 or 20. Really, I saw the movie at the time as through a glass darkly; seeing it in the context of the themes and ideas of this class was revelatory. I came away really excited about it. While the picture still doesn't mean quite as much to me as "Mulholland Drive" (or even as much as a Coen brother picture like "Miller's Crossing", one of the handful of movies I've had to go back and see a second time during its initial theatrical run), it is quite a work of art, imbued with that Coen brothers genius. The sound design alone is amazing. I love how you can never quite be sure what you're hearing through the hotel walls: is that laughter or crying, sexual pleasure or disgust? It's a trip though Joel and Ethan's psyche as much as it is through Barton's. (In the discussion someone tossed out "Repulsion" as a key reference, which I thought was spot-on; I saw a lot of "Eraserhead" this time, myself.)

Having introduced "Singin' In the Rain" by taking us all the way back to ancient Greece and the festivals of Dionysus to show us how the musical sparked modern drama (in short, the choric dithyramb included a singer and a chorus; as soon as more than one person was introduced you had conflict, and thus drama), it came as no surprise that Matty introduced "Barton Fink" with a lecture that attempted to do nothing less than put the film in the context of the entire history or art and theory. Right up my street, that sort of thing.

His talk alit briefly on a range of subjects. The distinction between film theory and film criticism. (What we do in this class is theory, not criticism, he maintained.) Different schools of theory and criticism. (He mentioned formalism, historicism, the German Marxists--I assume he was referring to the Frankfurt School here--before declaring himself a partisan of the New Critics of the 40s.) Changes in technology (which in my days of Marxist study we would have called the "means of production") such as Ford's assembly line and the commensurate changes in the culture and society which led to movies' emergence as a mass entertainment.

Modernism and Duchamp's seminal painting "Nude Descending Stairs" got a little mention, as did the rise of consumerism and disposable income; the ascendancy of kitsch (e.g., hotel-wall paintings such as the one of the girl on the beach in Barton Fink's room); and, most crucially, the differentiation between high art and low. This is very much the schism of “Barton Fink”. The transition for Barton from New York (high culture) to L.A. (low)--or, rather, the transition into his psyche, according to the analysis we pretty much agreed upon in the post-film discussion--comes through a shot of waves crashing against a rock. (A fella in the class theorized that the water is his unconscious and the rock is his writer’s block. Nice one.)

All that, and Matty also wanted to delineate the New York theatrical community out of which playwrights like Fink came, whose members Hollywood had been wooing at the time the movie is set (1941). Fink was based on Clifford Odets ("Awake & Sing!", "Waiting For Lefty"), himself lured out to LA to write for Hollywood. A new naturalistic style of acting was emerging out of the school started by Stanislavski in Russia, which in America was being led by the likes of Stella Adler and Lee Strasberg; Eugene O'Neill merged it with a naturalistic theatrical style.

It was an avowedly socialist scene. Fink wants to make works of social realism that will glorify and uplift the common man. Not lost on the Coens' keen eye for irony, of course, is that he actually condescends to them. ("I create!," a frayed-nerves Fink yells at the rubes at one point as a way of distinguishing himself from them). When Fink finally meets an actual common man, Charlie (John Goodman), a fellow guest at the Hotel Earle, he's patronizing, refusing to let his pre-conceived notions be altered by actually listening to a word Charlie has to say. “I could tell you stories,” Charlie keeps saying. When the hotel scrambles the shoes left outside the door for shining, Fink even literally puts himself in the common man's shoes, lowering his feet into Charlie's shoes as he sits trying to overcome writer's block. They don't fit.

HUAC was the hidden theme of the film. Aside from not listening, Adam said, remember one of the things for which Charlie is most furious at Fink: Fink told on him. (He called the front desk to complain about the noise.) Fink is literally a fink. "Karl Mundt" (Charlie's murderous alter-ego) is the name of the real-life vice-chairman of HUAC. (Odets himself named names in 1952 and was racked with guilt about it for the rest of his life).

Adam's theory is that Charlie is actually a character created by Barton, and he resents being stuck in Barton's mind. (That's why "You're just a tourist, but I have to live here"). If you look quickly in the beginning you'll see that a character in Barton's play is carrying a case and wearing an overcoat like Charlie. Charlie's the part of Barton that wants to help, run amok. "I'LL SHOW YOU 'THE LIFE OF THE MIND'!"

Adam tossed out some more fun Fink theories: the two hard-boiled noir detectives, who push Barton around and don't bother to disguise their anti-semitism? They represent Italy and Germany. And that box, what's Barton carrying around in there? The head of his muse. (If you listen to the script Barton finally comes up with as it's read aloud, the word "head" is repeated more than any other.) John Mahoney's character is of course based on Faulkner, who, during his miserable sojourn in Hollywood, wrote a picture called "Slave Ship" (1937). Its star? Wallace Beery, the very star of the wrestling picture that Fink is supposed to be writing and just can't get off the ground.

They're all so miserable. It leaves you wondering, did any writer come through the process with anything like his sense of equilibrium intact? Actually, my all-time favorite writer, the immortal P.G. Wodehouse, wrote a bunch of funny stories and novels borne of his time as a writer in Hollywood. He seemed to rather enjoy it more than not.

The communal "Stop Making Sense"

Friday, July 29, 2011 at 01:39PM

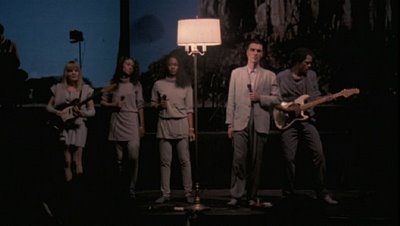

Friday, July 29, 2011 at 01:39PM A few thoughts after seeing "Stop Making Sense" on the big screen at the Music Box last night:

When I was 14 or 15 and Talking Heads was my favorite group, few things were as eagerly anticipated as when “Stop Making Sense” would come to the theater in uptown Athen, Ohio, as it would from time to time in the mid-80s. Maybe Christmas when you were a kid. We would rent the movie on VHS from time to time, and those were the days when renting a video was kind of a big deal. I remember calling up a friend and saying, "Hey, I got "Stop Making Sense". Come on over." (That's all you had to say.) Still, that didn't compare to seeing it in the theater with an audience. I remember walking past the poster outside the theater in the days leading up to the event, flush with anticipation. Was it the Athena where it would play, or at the Varsity across the street? I think the Varsity, if memory serves. No longer there.

And then the night would come. The movie itself would build, each musician coming out gradually, from David Byrne solo with a beat box, next joined by Tina Weymouth for "Heaven", which I thought was about the most beautiful song I'd ever heard. As the full band assembled the atmosphere in the room would heat up, the air becoming more and more electric, the funk more and more irrestible, until finally some spark would ignite the place and many in the audience would bound from their seats and dance in the aisles. At the time it was fun for me just to watch, you know, grooving on the energy of the dancers, most of them college students.

It's hard for me to communicate just how much the movie meant to me. I suppose it's always been a sort of benchmark: here is the level of energy and intensity and joy that is possible. For me it's nothing less than a metaphor for how a life worth living should be lived. I suppose it did for me what, say, Dylan did for another generation (and for me too, I should say): gave me the right attitude. Was that "large automobile", the "beautiful house" and the "beautiful wife", really where it was at? Shouldn't life be a creative endeavor? Think of Bob and Judy: "They might be better off, I think/The way it seems to me/Making up their own shows/Which might be better than TV." And, perhaps most importantly, it's a vision of community. And though they never make a big deal about it, I wouldn't want to underestimate the impact it had on me that this community was black and white, men and women.

The screening at a packed Music Box theater was introduced by Greg Kot and Jim DeRogatis, co-hosts of the rock & roll talk show "Sound Opinions". "I hope you're ready to sweat," Greg said, going on to speak passionately about the movie. For his part DeRo made a little invidious comparison to "The Last Waltz" and what he considers that movie's deification of the performers (I couldn't disagree more), but then he said to watch for the way the musicians look at each other: outside of making love, he said, there are few human activities as intimate as making music. The gazes are something I've always loved about the film as well.

Seeing it on the big screen this time, I had to marvel again at Jonathan Demme's mise-en-scene (fancy term which I like to think of as "modification of space"): the angles, the shot distances, the camera movements. The movie is such a sustained miracle of filmmaking and performance and stage conception all coming together to create moments that can only be described in one way: transcendence.

I watch the movie on DVD at least once a year. But seeing it on the the big screen, Byrne sitting up at the beginning of "Swamp" against that red backdrop, hair slicked back and eyes wide, a close-up filling your field of vision, is just a qualitatively different experience.

Just like in the old days, it was "Life During Wartime" that brought them out of their seats. I sat grooving and bopping in my seat. Finally, though, when Byrne emerged with the big suit and "Girlfriend is Better" kicked in, I leapt from my seat and down the aisle to join the community in front of the screen. The band brought it home for the celebration that was "Take Me To The River" and "Crosseyed and Painless". As Byrne introduced the band we clapped and cheered for each in turn.

As we filed out I overheard a guy tell a 20-something, "That's what it was like to be young in the 80s". I heard another excited young person say that she'd never seen it before. Someone said she hadn't seen it since she was seven, but it was just like she remembered it. Some people had brought their kids. Outside the theater I saw a smiling boy bound a step or two in front of his dad. Trying to process what he'd just seen these crazy adults doing, he asked over his shoulder, "Why do people get up and dance?" With the tone of a man happy to have shared something special in his life with his son, his dad answered, "It's a tradition".