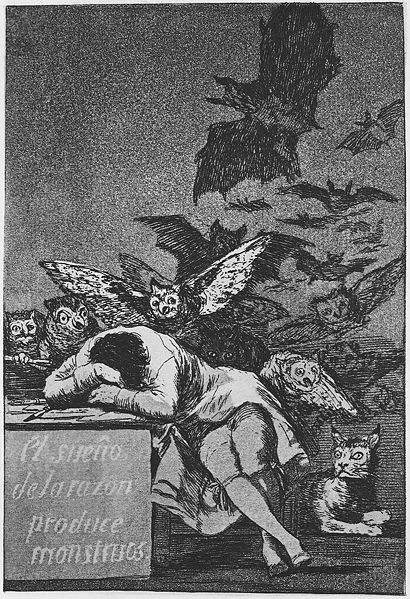

Karolyn and I burrowed deep into the bowels of the Art Institute to attend a lecture by one of Chicago's great rockers and all-around creative guys, Jon Langford. He appeared in a subterranean auditorium as part of the Institute's “Artists Connect” series, billed as “where local artists talk about how their work connects with artists of the past.” Langford’s connection is with Goya, whose devilish eye held a twisted mirror to society that showed its true soul. In a society still run by fear, Langford noted, Goya couldn’t be more relevant.

I have a personal experience with Goya myself. In 2012 I explored the Prado, something I've wanted to do for 20 years, and saw three flights of his stuff, from the pastel cartoons of leaping lords and ladies that he made as a young court painter, to his “black paintings,” when he had a freak-out and smeared the walls of his house with his nightmares. (He "had a freak-out." Way to put it in social and historical context, Pfeiffer!)

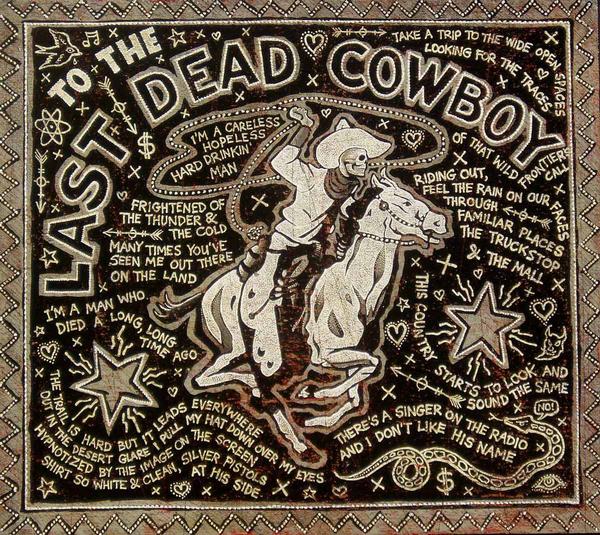

Of course, since it was Langford, he appeared with guitar in hand. He turned the talk into a concert, jamming out on songs like “The Country is Young,” “Sputnik 57” and “To The Last Dead Cowboy.” The music passed my litmus test for proper music, by which I mean to say it could have been played by the guys sitting around that circle in the Elvis Presley ’68 comeback. (Okay, that’s one of my litmus tests for proper music.) His lyrics, of course, are quite another matter indeed. Those could have only come from the surrealistic imagination of Jon Langford. Langford always plays with a fiery rock ‘n’ roll attack, even if he’s playing acoustic, even if he’s singing country or folk songs.

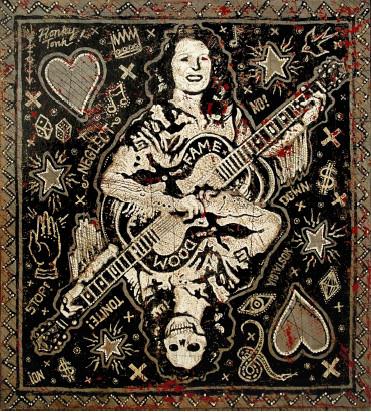

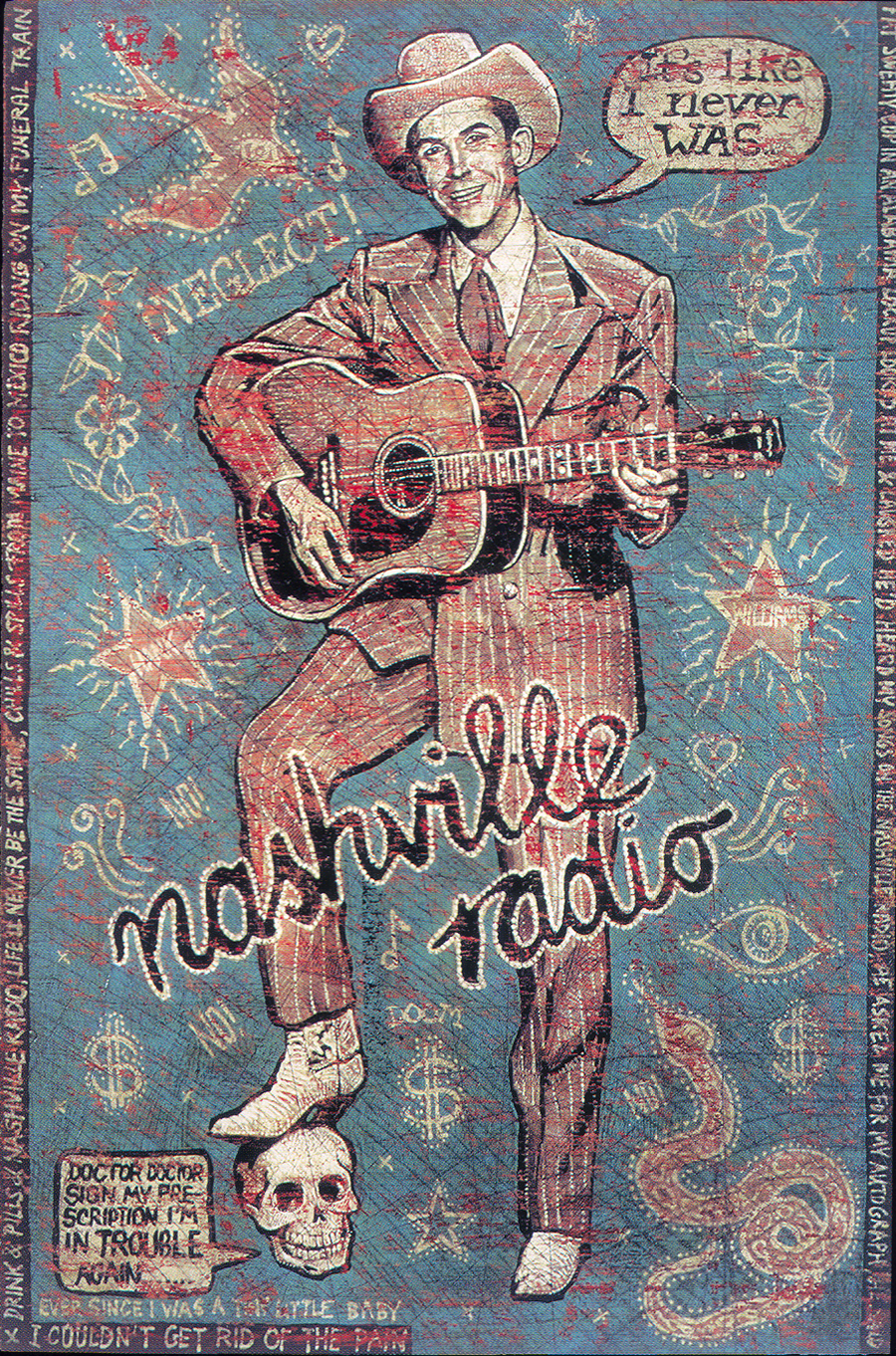

He'd made a slide show to go with his talk, toggling back and forth between Goya’s images and his. Many of his works are illustrations of song lyrics. Motifs include skulls, cowboys, cowgirls, and country music greats, sometimes blindfolded or X-ed out as though in a Stalinist wipe-out. There were slides from his life as well, and the lecture became a personal story about the rather twisty road that brought Jon to country music.

He was a boy from Wales born in the late 50s. In the 70s he was excited about punk rock and art school. During his art school days in Leeds, he co-founded the Mekons, the seminal second-wave punk band. They dealt in small ‘p’ politics, he said: the everyday things that were around them. He brought up a slide of the Three Johns, one of his innumerable side projects, looking like art-school pranksters togged out in djellabas, or like the jawas from "Star Wars" (an admitted big influence).

He told the story of how the Mekons got into country music back when no one in their circle was into it. (It'd be interesting to know if Elvis Costello's "Almost Blue" was an influence. I think that record was way ahead of its time in turning people on to the beauty and strength of country songs).

He talked about moving to Chicago and hanging with the Sundowners, the legendary Chicago honky-tonkers. Later he went looking for the roots of American music, a pilgrimage many of us take. (Karolyn and I are about to take a similar journey into the roots (routes?) of American music, to Memphis, Nashville and New Orleans.) He talked about discovering Tootsies Orchid Lounge in Nashville, a “beautiful graveyard” with walls covered in amber, shellacked playbills of C&W stars.

He pasted the people who run the American country music business as “Stalinists,” and he meant something quite specific: the way they consigned the country greats he loves to non-person status and shot them down the memory hole. He pointed out that Nashville radio isn’t playing much Hank Williams or Bob Wills and Texas swing these days. He is fascinated by the moment when an artist becomes an employee: that is, the moment when the pen hovers about the contract. In the music business, people are food for machine.

(Much to his bemusement, some industry people came to one of his shows and liked the images enough to commission him to do a record cover. Everyone has his price, Langford admitted to audience laughter, and that day mine was $6,000.)

He performed “Hank Williams Must Die”: It seems Hank Williams actually mentioned Stalin by name in a song and Stalin heard the song, apparently enraging the dictator. The song is Stalin's imagined response.

Even though he made no mention of it, all of this put me in mind of the Mekons' urgent song “Amnesia,” which fascinates me. History and memory is what it’s all about. (“I forgot to forget to remember.”) As the song begins, “it was a dark and stormy night" and we’re on a storm-tossed slave ship “taking rock & roll to America,” that is, bringing Africans to America, where they invent the music that then goes back across the Atlantic to turn on English kids. It’s about two different British Invasions: the musical one in the 1960s that brought the Beatles, the Stones, the Animals to these shores, and which reawakened America to its own musical roots. Also the one in 1812 where the Brits burned down the White House.

It all swirls around until it finally explodes, riding in on a strumming dulcimer straight out of “Battle of Evermore,” a hurricane that is the harvest of all the forces the song’s unleashed so far. There’s a rousing battle cry of “truth, justice, and Led Zeppelin!” but you don’t know whether it’s rallying you to join the rock & roll battle or the political battle, or both, or to what end.

There's a lot more in it (Mardi Gras Indians, segregation, the Shining Path, the drug trade), but that’s a few things I hear in this roiling maelstrom of race and America and England, and cross-Atlantic trade and cultural give-and-take.

So. Back to the talk. It was dense with references, musical and artistic. He mentioned Otto Dix, the German painter and printmaker, and how Goya influenced his own ruthless depictions of war.

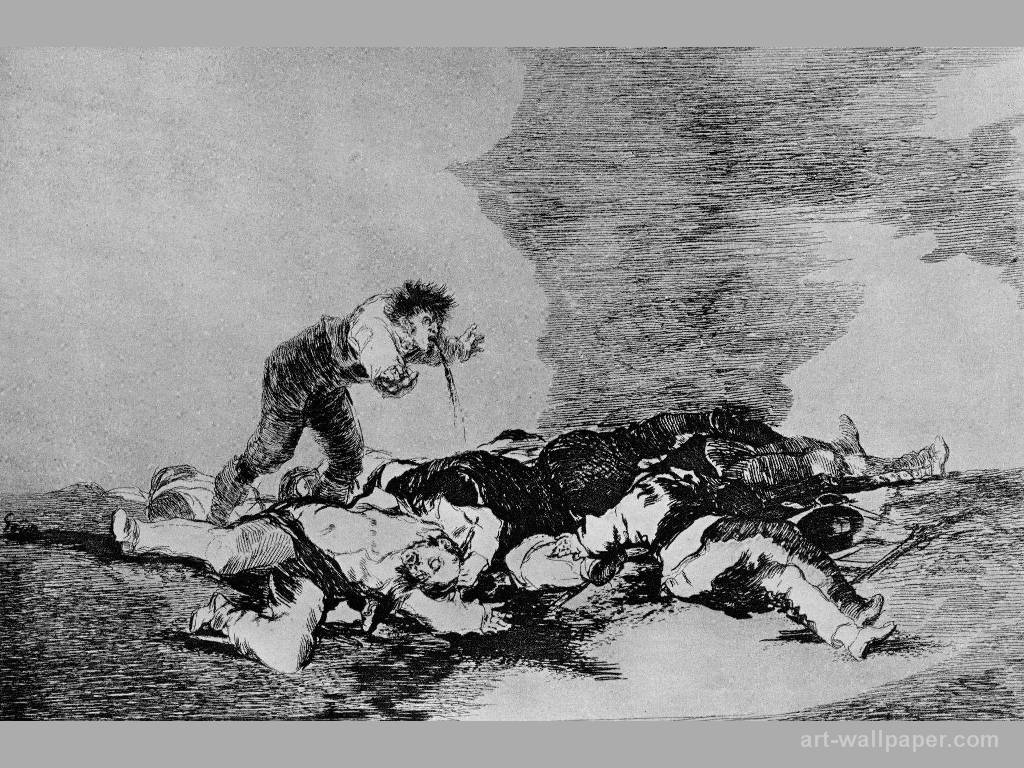

Langford was particularly shaken by Goya’s “Caprices” (Los Caprichos), the sheave of etchings that lacerated 18th-century Spain. Goya published it in 1799 but withdrew it due to fears of the Spanish Inquisition. Likewise, Langford was hard hit by the "Disasters of War," Goya's etchings about the Peninsular War (1808-1814) that found Spain at war with France, pulled into the maelstrom of Napolean’s post-French Revolution conquests. He showed us “This is what you were born for,” plate twelve from Disasters of War, showing a man puking over a pile of bodies. (Goya kept it real.)

Langford was knocked out by “The Dummy,” which he called one of the great images of humanity being tossed about.

There’s something very moving, very hopeful and unbowed, about Jon Langford. For one thing, he's still a believer in the socialist project, and though it wasn't a topic of his talk, he's as acidic about those who betrayed true socialism as he is about those who betrayed "true" country music. (I think of "This Funeral is For The Wrong Corpse," the Mekons song about how the reports of socialism's death were wildly exaggerated: "How can something be dead when it hasn't really happened?")

And he loves his adopted home, the United States of America, with a fierce, embattled love. He ended with “Lost in America,” a song that always moved me. We can still turn things around. Let's keep the flame burning, and let's fight those who would snuff it out. Langford made it sound as if the project of keeping America's flame burning and keeping our music's flame burning is one and the same. Which of course it is. As Goya showed him, the best art is about what’s going on immediately around you.