"I demand that a film express either the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema. I am not at all interested in anything in between; I am not interested in all those films that do not pulse."-- Francois Truffaut

Like the season itself, the summer class taught by Adam Kempenaar and Matty Ballgame, co-hosts of the movie talk show Filmspotting, must draw to a close, and it did so on August 10. We'd done three-movie units on the Star and the Writer; now "Movies About Movies: Hollywood Looks At Itself" wound up with a look at the Director. Concerned more than any of the others with the process of creation, of actually making a film, it was a unit suffused with the joy and the agony of cinema, which is to say of life.

For the last time the teachers came up with a three-movie series, riffing on variations on the theme of the Director and doffing the hat to three of the great ones: Preston Sturges with "Sullivan's Travels" (1941), Fellini with "8½" (1963) and Truffaut with "Day For Night" (1973). The final class was a bit of a coda, two documentaries about directors trying not to lose their minds while deep in the jungle and up to their necks in tortured projects: "Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse," about Francis Ford Coppola and the making of "Apocalypse Now," and "Burden of Dreams" chronicling Werner Herzog and the shooting of "Fitzcarraldo".

And as the class had done all along, this final unit constituted a continuous reaffirmation of my vows of love to cinema. I think of that great moment in “Day For Night” when everything starts to go right for our hapless film crew, everyone is firing on all cylinders and Delerue’s joyous theme “Le Grand Choral” erupts, and Truffaut as the director proclaims the central truth of his life: “Cinema is king!”

The movies they’d chosen happened to be important to me for personal reasons. At many times I had cause to cast my mind back 20 years, to think about where I was then and where I am now. I saw "8½" and "Day For Night" at a time when cinema was just becoming my life. It was 1990 or '91 or so; I was doing a minor in film at Ohio University in Athens. My dream then was to be a director myself. I was going through film history for the first time, perusing the shelves on the bottom floor of the OU library and checking out their scratchy old videotapes. So many great films I first saw that way. “8½” for sure. I remember a barely viewable "L'Avventura"; despite the print, the mystery and the power of the film came through.

And I think it was those two documentaries with which we ended, "Hearts of Darkness" and "Burden of Dreams," which made explicit for me the subtext which I was experiencing, watching these pictures now. The feverish, mad quest, the sense of "I live my life or I end my life with this project": that’s the way I had hoped to live. Here are artists climbing their Everest. (I was gonna say “metaphorically,” but in Herzog’s case maybe not so much). As Herzog puts it in “Burden of Dreams,” telling the story about the time things looked bleak for “Fitzcarraldo” and his financiers asked him if he even cared to carry on: How could you even ask me that? Otherwise I would be a man without a dream. And I don't want to live like that.

One thing the teachers asked us to keep in mind over the weeks: in the unit on the Writer we were looking at people who were struggling. Now we're examining people who have found success. So what do you do when your dream comes true?

Sullivan's Travels

The unit kicked off on July 20 with a screening of 1941’s "Sullivan's Travels," directed by the great Preston Sturges. "Barton Fink," the movie that culminated our look at the Writer, actually worked as a perfect setup for this one. Fink, as you’ll recall, wanted to write something that would uplift the common man. Indeed, Hollywood in the late 30s was steadily attempting to do "uplift" (literary adaptations, movies about composers, etc.). Joel McCrea plays a director contemplating his next picture: he wants it to be a “commentary on modern conditions. Stark realism. The problems that confront the average man!” To which his perplexed producer gives the classic rejoinder, “But with a little sex it it.”

Adam pinpointed the secret theme of the movie: as an artist, how do you relate to your audience? In the wake of the depression, rich Hollywood people had nothing in common with the people actually going to see their movies.

(McCrea proposes to call the picture "O Brother, Where Art Thou?"; we watched a clip from that Coen brothers picture, in many more ways than the titular a homage to "Sullivan's", the scene where Clooney and Tim Blake Nelson, on the run in the 30s, have ducked into a movie theater when a chain-gang is marched in under armed guard.)

The wealthy McCrea hits the road in hobo gear to see Depression-wracked America firsthand. Along the way he meets Veronica Lake (sigh). The picture is kinetic with zippy dialogue and rollicking comedic set pieces. However, in an unprecedented move for a screwball comedy, midway through there’s an astonishing montage to rival Dorothea Lange showing the human suffering they encounter.

As a bit of set-up we had watched a clip from Woody Allen's "The Purple Rose of Cairo," in which Mia Farrow's character enters a movie house every day to step out of her tiresome 1930s life and into the world of singing, dancing and nightclubs on the screen. Escapism is one of the main reasons people have always gone to the movies. Film theorists like to stress the idea that film is significant not for what it is but what it does. But what then is the function of film? To educate? To instruct? To make us forget about our troubles for a while?

Sturges on the one hand seems to be making an argument in favor of comedy and escapism. As Adam pointed out, though, isn't he actually having it both ways here? The irony is that this screwball comedy is in every way the political equal of something like "The Grapes of Wrath." Consider the scene where McCrea, having found himself pressed into a chain-gang, is brought into an African-American church which hosts the prisoners' great treat: movie night. (I'd first sought out "Sulllivan's Travels" in the 90s after Dave Marsh described this scene to me and the impact it had had on him.) They show a Mickey Mouse cartoon and the audience of white prisoners and African-Americans collapses together in laughter. It's a great illustration of Sturges' humanism and the communal experience of the movies. McCrea looks around the room, and he finally gets it. The common man needs this more than he needs a thousand "O Brother, Where Art Thou?"s.

The older I get, the more convinced I am that there can be no nobler or higher function of film than this: to make us laugh.

Next up on July 27, was...

8½

This was one of the movies that made me fall in love with cinema in the first place. I detected an undertone of carping amongst my classmates to the effect that the picture is somehow heavy or tough-going or something, but to me “8½” is shot through with joy and humor. I can't put it any better than James Monaco: "What makes Fellini a supremely important filmmaker is that he captures the life force. It bubbles off the screen and we partake of it...The Germans have a word: 'weltschmertz.' Like all such intellectual terms, it's supposedly untranslatable, but it has something to do with world pain, a kind of pervasive sadness. There's a little of that in Fellini but there's much, much more of what we might call 'weltfreude,' the joy that suffuses life. It has to do with food and drink and sex and children and art, not necessarily in that order. I guess it's Italian."

Of course "8½" is about poor blocked director Guido (Marcello Mastroianni) and his inability to get his next movie off the ground. As with "Mulholland Drive," though, it's the fluid filmmaking itself that carries me off. Along with Lynch, Bergman and Maya Deren, Fellini is one of the few directors who can truly capture on film the feel of a dream. So many magical moments: Guido's dream of his warm, happy childhood in that Italian farmhouse, triggered by the incantation "Asa Nisi Masa." The moment when, like a vision, Claudia Cardinale appears to offer to him the healing waters. That joyous Nino Rota score.

And then there is that final sequence, which made tears spring to my eyes this time, hitting me in a way that I'm sure it couldn't have 20 years ago. Before taking his wife's hand so that they too may take their place in life's rich pageant, Guido suddenly feels rejuvenation well up within him. Internally he asks for forgiveness from her whom he has treated carelessly, from the loved ones in his life whom he could never show love. There's such honesty in it, and such acceptance.

"What is this flash of joy that's giving me new life? Please forgive me, sweet creatures. I didn't realize, I didn't know. How right it is to accept you, to love you. And how simple!...Everything's confused again, but that confusion is me. How I am, not how I'd like to be. And I'm not afraid to tell the truth now, what I don't know, what I'm seeking. Only like that do I feel alive and I can look into your loyal eyes without shame...Life is a party, let's live it together... Take me as I am, if you can. It's the only way we can try to find each other."

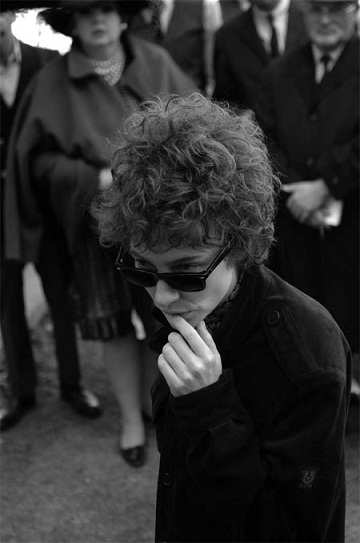

To demonstrate “8½”’s influence, the teachers ran a couple clips, one from Woody's homage, "Stardust Memories," and one from "I'm Not There," Todd Haynes' cinematic poem about two of my abiding fascinations: Bob Dylan and 60s cinema. As I wrote in my review of "I'm Not There" at the time, "the [Cate] Blanchett section takes place in 60s-cinema-land, as she walks in Mastroianni’s shoes through the black-and-white world of Fellini’s '8½'." (I love the bit where, after they roll around with Dylan on the lawn, we see the Beatles in the background being chased away by a horde of teenage girls. A little nod to Richard Lester's "A Hard Day's Night," of course.)

Haynes is doing a lot of things at once here. He's saying that Dylan was doing in his field what the likes of Fellini were doing in theirs. He's noticing that Dylan’s interlocutors in “Don’t Look Back” were very much like Guido’s in “8½.” And he's suggesting that, just as I've always imagined, Fellini's movies were a huge influence on Dylan's music taking off in pursuit of a more personal, surreal vision. "To dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free..."

Next up on August 3, was...

Day For Night

Ah, Francois Truffaut's wonderful "Day For Night." A film about making a film. Truffaut himself plays a director; Jean-Pierre Leaud, the actor whom we watched grow up on screen as Antoine Doinel (a Truffaut surrogate), plays an actor. (Leaud was sort of the Daniel Radcliffe of his time, maybe, except without the magic wand, and if I’d seen any of the Harry Potter pictures except that last one). Jacqueline Bissett, a sex symbol of the 70s, plays a British actress cast in a French movie, very much as she was in real life.

Like I mentioned at the top, I first saw "Day For Night" when I was doing a minor in film at OU at the onset of the 90s, when I dreamed of being a director myself. I remember seeing it at a point when I was making films myself for class, hanging around the equipment rooms and checking out cameras, cutting film in the editing room and conferring with the grad students (who were TAs with their own dreams of being filmmakers). "Day For Night" presented a vision of the sort of community that I hoped to find, of the creative life.

There was one moment in particular that moved me then. Leaud, so comically earnest, runs around asking all and sundry, "Are women magic?" At the time I was 20 years old and wondering at the mysteries of women myself. (What I didn’t understand then was that the confusion never really goes away.) When he finally poses that question to Bisset, her reply moved me. She says something along the lines of, Of course they're not. Or else men are too. Everyone is magic and everyone is not. For all her emotional problems, Bisset's character is a very wise woman. Seeing the film now, though, 20 years down the line, a divorced man, it was another line of hers that stirred me. When Leaud begins to disparage the girlfriend who has abandoned him, Bisset gives him a little talk. By despising her you're only degrading yourself, she tells him. The truth of the line resonated deeply within me.

We led into "Day For Night" with a clip from Truffaut's very personal "The 400 Blows," the film that introduced Leaud. Little Leaud has a "Eureka!" moment with his Balzac. As Adam put it, he can't help but let the art creep into his life, plagiarizing Balzac for his own essay. Though he had a real transformative experience with art, his teacher doesn't acknowledge it. He's all about, "Be obedient. Behave. Follow the rules." I wonder, though, if that sort of experience with authority figures doesn't just fuel the artistic spirit. It reminds me of one of my favorite quotes from Alexander Cockburn: "A childish soul not innoculated with compulsory prayer is one open to any religious infection."

"Day For Night" is about the ideal versus the practical realities of shooting, on one hand. We keep seeing Truffaut tossing and turning at night, dreaming of being a boy reaching out for stills of "Citizen Kane" just out of reach. He knows the movie he's actually making is not really that great, but he's trying to make it as good as he can. For me, implicit in the greatest art--whether it's movies or rock & roll--is a vision of a way to live. You have to try somehow to live up to the possibilities, the potentialities you glimpsed in this stuff that made you feel more alive than anything else ever has. When you're young you dream of making your "Citizen Kane." And what you realize 20 years later is that life becomes about somehow holding on to that ideal, reaching for it, while at the same time accepting that real life must inevitably fall short. And at the end of the day that's okay...because it has to be.

At the end of the class we voted on our favorite film of the course. The winner was "Day For Night". Nobody could articulate exactly why, but I think it's because it's about love for movies. It's a warm vision of community, cast and crew on a journey, living together, coupling and uncoupling. None of them would dream of having it any other way. As one of my favorite characters, a fetching script supervisor, puts it: I’d leave a man for a film, but never a film for a man.

It all made me think of a line from David Byrne: "If your work isn't what you love, then something isn't right."

And finally, on August 10...

Hearts of Darkness and Burden of Dreams

It was our final class. Tables groaned with Garrett's popcorn and other comestibles brought in by classmates and myself. The Doors' "The End" wafted through the room (thanks to Matty, presumably). Nice touch. "This is the end, beautiful friends..." And so it was. And it led into...

..."Hearts of Darkness," the first of our two "never-make-a-movie-in-the-jungle" documentaries, Eleanor Coppola's film about her husband Francis and the tortured shoot of "Apocalypse Now". It was back to the idea of giving birth to a film as a bloody process, full of agony and chaos. It was fun to compare these glimpses of movies actually being made to the fictional depictions.

We only had time to watch about half an hour of Coppola's mad quest and then we popped in Les Blank's "Burden of Dreams," which records Werner Herzog's mad efforts to make a movie about pulling a steamboat over a hill in the Peruvian jungle. Observing Herzog striding atop the boat like Ahab at the helm of the Pequod, you couldn't help but feel like the 70s and early 80s were the last times that directors like characters out of novels walked amongst us. Some words of Herzog's near the end of "Burden" seemed like a fitting cap to a class which had been about dreams on so many levels:

"It's not only my dreams. My belief is that all these dreams are yours as well. And the only distinction between me and you is that I can articulate them. And that is what poetry or painting or literature or filmmaking is all about. It's as simple as that....this might be the inner chronicle of what we are. And we have to articulate ourselves. Otherwise we would be cows in the field."