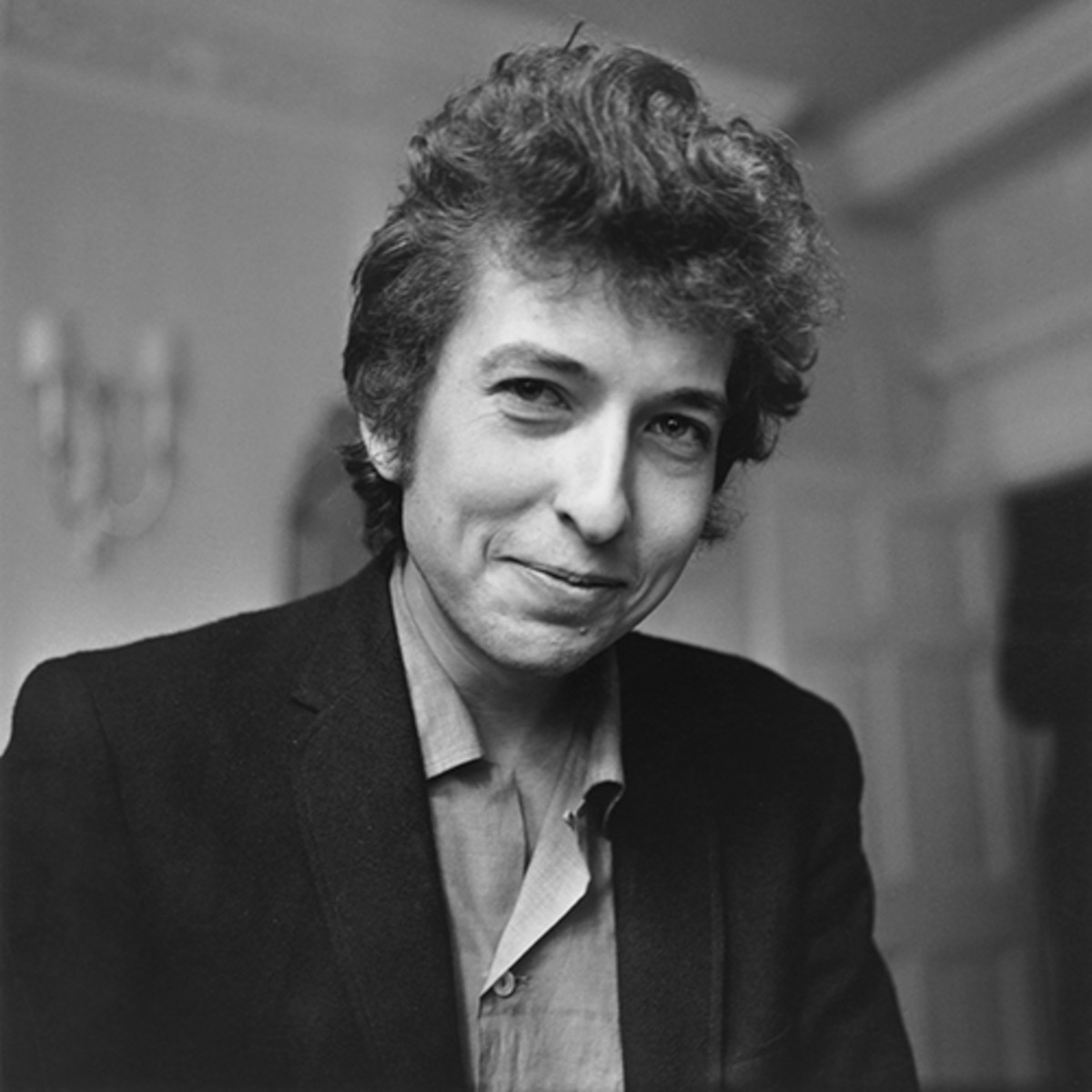

What can you say about Bob Dylan on his birthday that hasn’t already been said? The only perspective I have that no one else does is my own personal experience. Even then, if I say that he’s always seemed to be singing my story, even while telling his, I can just as easily imagine you saying the same. Perhaps that’s a measure of his gift. Still, on his 80th, I cast my memory back over a handful of scenes from my life that will always be evoked by his songs—moments his songs created, in a sense. Going to a debate on the issue of mandatory drug testing on the OU campus while I was still in high school, in ’87 or ’88 (Timothy Leary vs. a former head of the DEA), where they played “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35” over the PA system pre-debate, to riotous audience reaction. This was certainly the first time I ever heard a whole auditorium full of people sing along jubilantly to that joyous chorus. (The audience clearly didn’t understand it’s obviously a religious allegory. Ahem.) A plane lifting off in ‘88 as "Like a Rolling Stone” kicked in on my Walkman, and the possibilities of life and travel and adventure seeming to open up endlessly in front of me. Bob gazing down at me from the poster of the cover of “The Times They Are A-Changin’” on the wall of my OU dorm room, freshman year ’89-‘90. Road trips where I’d pop “The Basement Tapes” into the tape deck just as soon as I got the motor turning (it’s still my favorite road-trip album). Moving to Chicago in ‘93 and seeing my first Dylan concert in April of ’94, four days after my birthday. What I remember most is being lifted away by a stirring “Jokerman,” Bob’s poker-face hovering in the spotlight. Seeing a friend who’s still the only cat I’ve ever known who could sing all the words to “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” do just that at a memorable open mic. An evening in the mid-‘90s: I’m in my mid-twenties. It’s late at night and “Desolation Row” is playing softly. I’m sitting up with a fellow I don’t know too well, an African-American gent 20 years my senior, a friend of a friend‘s mother. Everyone else has turned in and we just sit there and sing along with the song, both of us tickled the other knows every word, down to the phrasing. Nothing more really needed to be said. I never did see him too much after that, but it was a bonding moment I won’t forget. And then in some of my darkest times, finding tremendous consolation and strength and courage and acceptance in songs like “Most of the Time” and “Shelter from the Storm.” I think of all the shows I’ve seen down the years: the way a local audience always erupts after that line about “the winds in Chicago” in “Cold Irons Bound.” Dylan grinning from ear to ear from behind the keyboards at the edge of the stage, as a woman in the side balcony above him dances with utter joyous abandon, acting as though she might just obey the lyrical injunction to “throw your panties overboard” in “High Water (for Charley Patton).” That was at the Vic, I think. Going to concerts with Karolyn: hearing him play “Desolation Row” at United Center while huddled up next to her. I was probably singing along softly. Going to the big Americanarama all-day concert, where Karolyn introduced me to my first “tailgating” experience—Dylan headlined a show also featuring Richard Thompson, Wilco, and My Morning Jacket. Watching him seemingly baffle the crowd that night rather like he must’ve in the ‘60s: “Ballad of a Thin Man” took on an especial resonance. Dancing with Karolyn to “Soon After Midnight” at our wedding. (A dark choice, perhaps, but we liked the sound of it.) These are just a few scenes from a life; I could have chosen a hundred more. We have been extraordinarily lucky to live at the same time as Bob Dylan. Assuming there are still people around 500 years from now, our descendants will understand that we lived in a historical period like few others. Happy 80th, Bob. Thank you for the music. I can’t imagine my life without it.